Intellectuals as Sacrificial Heroes A Comparative Study of Bahram

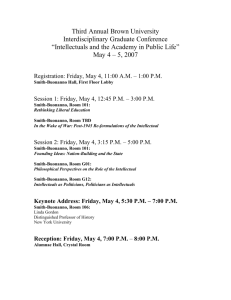

advertisement