Off-Grid Energy - UK Government Web Archive

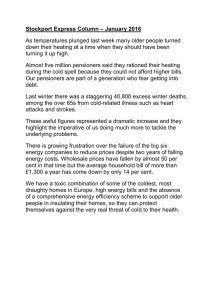

advertisement

Off-Grid Energy

An OFT market study

October 2011

OFT1380

© Crown copyright 2011

You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any

format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view

this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or

write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9

4DU, or email: psi@nationalarchives.gsi.gov.uk.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: Marketing,

Office of Fair Trading, Fleetbank House, 2-6 Salisbury Square, London EC4Y

8JX, or email: marketing@oft.gsi.gov.uk.

This publication is also available from our website at: www.oft.gov.uk.

CONTENTS

Chapter/Annexe

Page

1 Executive Summary

4

2 Introduction

9

3 Overview of the off-grid market

13

4 Heating Oil

56

5 Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG)

127

6 Microgeneration

168

7 Conclusion and recommendations

200

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1.1

Four million households in the UK are not connected to the mains gas

grid and therefore use other fuel sources for their heating. These 'offgrid' fuels include kerosene heating oil, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG),

coal, wood and electricity, with microgeneration technologies, such as

solar panels, increasingly playing a role.

1.2

In the winter of 2010/11 some heating oil customers experienced high

prices and delays in supply, causing some commentators to question

how well the markets for heating oil and off-grid fuels more generally

were working. In January 2011 the OFT brought forward planned work

into off-grid energy supply and launched a market study to assess

whether and how the competition and consumer protection regimes

could bring about better outcomes for consumers.

Off-grid customers and fuels

1.3

The off-grid community is large, geographically dispersed and diverse: it

covers all social grades, urban and rural communities, households in fuel

poverty as well as households that are not, and embraces a wide range

of fuels.

1.4

The markets in England, Wales and Scotland are broadly similar, with

between 12 and 25 per cent of the population off-grid, and with heating

oil and electricity being the main fuels used. Northern Ireland is very

different. Fully 80 per cent of households are off-grid and around 80 per

cent of these use heating oil. However, a higher proportion of the offgrid population in Northern Ireland has the option to connect to mains

gas. This reflects the relatively recent roll-out of mains gas networks.

1.5

There is limited potential for most consumers to switch between

different fuels – the cost of converting boilers means that such

switching is likely only when central heating systems are upgraded or

replaced. This means that the different fuels provide only a limited

competitive constraint on one another. There are therefore separate

OFT1380

|

4

markets for each fuel and the issues arising in each market are largely

distinct.

1.6

Our report focuses primarily on the markets for heating oil, LPG and

microgeneration; our key findings for each of these are set out below.

Heating Oil

1.7

Most complaints about heating oil concern high prices. Retail margins

only account for around 10 to 15 per cent of the price level, out of

which distributors cover their own costs, and some profit. Of the

variation in prices over time, over 90 per cent is explained by

movements in the price of crude oil.

1.8

Unexpectedly early, heavy snow in December 2010 triggered a sharp

spike in demand (40 per cent up on the previous year) at the same time

as hampering deliveries. Prices also spiked. To some extent this reflected

the increased costs of supply in tough conditions, but firms may also

have taken profit during this peak period. However, retail margins over

the year as a whole do not appear excessive – these margins are

generally high in the winter but low or even negative in the summer.

1.9

Our analysis of the market strongly suggests that competition is

generally working well. Almost all (97 per cent) of off-grid households

live in a postcode district served by at least four known suppliers.

Barriers to entry are low, and the industry is fragmented – the largest

player accounts for less than a fifth of the market and there are many

small players including relatively recent entrants. We found no evidence

of collusion between suppliers, and a variety of evidence that rival

suppliers compete on price.

1.10

We found higher concentration in supply in a small number of remote

areas – less than 0.3 per cent of off-grid households live in a postcode

district with access to only one or two suppliers. High concentration is

an issue for the supply of many products and services in such locations

due to sparse populations and access issues – this is not a finding

unique to heating oil.

OFT1380

|

5

1.11

We have, therefore, found no evidence of a competition problem that

would require either Competition Act enforcement or intervention to

regulate prices in this market.

1.12

We did, however, find grounds for concern about compliance with

consumer law. We found evidence of some heating oil websites making

claims that implied that they were independent or were comparing prices

from different suppliers, when this was not the case. We have already

taken action to address this.

1.13

We also received complaints that some heating oil suppliers were

charging a different price on delivery from that quoted when the order

was taken, particularly during the severe weather last December.

Carmarthenshire County Council took a successful case against this

practice in August of this year.1 The OFT is now examining this and

related practices.

LPG

1.14

Our initial assessment of the Competition Commission's Orders in the

bulk LPG market is that they have resulted in more customers switching

and some new entrants to the market: annual switching rates have risen

from 0.5 per cent at the time of the Competition Commission

investigation to 3.7 per cent in 2010/2011. The Orders have only

recently taken effect and we will continue to keep this under review.

1.15

We received some complaints about contract terms in bulk LPG,

including around limited termination rights in the face of sharp price rises

during the two year maximum lock-in period permitted by the Orders.

This is of particular concern for customers who are offered low but

temporary introductory rates as an incentive to switch. We are pursuing

this matter with the industry.

1

www.tradingstandardswales.org.uk/prosecutions/carmarthengboils.cfm

OFT1380

|

6

1.16

Our review of the supply of cylinder LPG brought to light some concerns

about the contractual arrangements between suppliers and dealers.

However, domestic heating represents only a small part of a wider

market for cylinder LPG (including industrial and commercial customers).

We may revisit this matter in the context of this wider market.

Microgeneration

1.17

Microgeneration is a relatively young industry and currently accounts for

only a very small proportion of off-grid energy supply. Take-up is

expected to grow substantially, encouraged by a combination of financial

incentives, other Government policy, rising costs for conventional fossil

fuels and a growing degree of environmental awareness. The

development of this market over the medium term should provide an

option for off-grid customers to switch away from fossil fuels.

1.18

However, there are several features of the industry that make mis-selling

a particular risk: not all technologies are suitable for all properties; the

technology is complex, so customers are dependent on an expert

assessment to make a decision; salespeople tend to specialise in one

technology and hence may not provide an assessment of the best

technology overall; there is little independent assessment available; and

prices are high so if mis-selling occurs the problems are significant.

1.19

Our evidence suggests that at present problems are not widespread, but

complaints started to increase over the summer. We expect most of

these complaints to be resolved by installers, and are confident that the

arrangements in place through the REAL Assurance Scheme Consumer

code of practice, will support this. It is crucial that such problems do not

undermine consumer confidence and thus the development of this

market. Alongside Local Authority Trading Standards OFT stands ready

to investigate specific allegations with a view to enforcement action as

necessary to stop unfair commercial practices in this market.

OFT1380

|

7

Next steps

1.20

OFT is actively examining a number of practices and engaging with

industry to ensure consumer law compliance, as set out above. We are

also working with trade bodies to ensure that their members are fully

aware of their obligations under consumer law, and that when things go

wrong consumers obtain adequate redress.

1.21

We welcome the recent campaigns by consumer and industry

organisations to advise households about the measures they can take to

buy early and reduce their exposure to risks.

1.22

Our study presents an evidence base on the off-grid population and its

experiences that we hope will be useful to relevant policy-makers,

notably DECC, Defra, the Scottish Government, the Welsh Government

and the Northern Ireland Executive. While by no means all off-grid

consumers are vulnerable, there is a proportion of the off-grid

community that is particularly vulnerable to high prices both in the short

term and the longer term, notably the subset of consumers in deep rural

locations with little choice of suppliers, poor housing stock, and low

incomes. Our view is that targeted assistance to the most vulnerable is

more appropriate than measures addressed at the markets more widely,

as in many respects the markets appear to be working reasonably well.

Thank you

1.23

Finally, we would like to extend our thanks to the many stakeholders in

the private, public and third sectors who generously contributed their

time and information to this study.

OFT1380

|

8

2

INTRODUCTION

2.1

On 25 January 2011, the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) announced its

intention to undertake a market study into the off-grid energy sector in

the United Kingdom (UK).2 This study was brought forward from the

OFT's 2011/12 programme of work in light of consumer experiences in

winter 2010/2011 of high and volatile prices and difficulties in receiving

supply, particularly in respect of heating oil, giving rise to concerns that

competition and consumer protection aspects of the market might not be

working well for consumers. Following a short consultation on scope,

the market study was formally launched on 15 March 2011.3

Scope of the study

2.2

The scope of the study relates to the domestic supply of energy to offgrid consumers for their heating needs.4 For the purposes of the study,

we define off-grid consumers as those households that are not

connected to the mains gas grid. This includes both those households

that are not connected to a mains gas supply but may be able to obtain

a connection, as well as those for which the mains gas grid is too

distant for connection to be either practically or economically feasible.

2.3

The following heating sources are commonly used by off-grid

households:

•

Heating oil.

•

Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) supplied both in bulk and in cylinders.

2

The press release is published at: www.oft.gov.uk/news-and-updates/press/2011/07-11

3

The press release is published at: www.oft.gov.uk/news-and-updates/press/2011/35-11

4

More information on the market study is available on the OFT website:

www.oft.gov.uk/OFTwork/markets-work/current/off-grid/ - including full details of the study

scope at: www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/market-studies/oft1302f.pdf

OFT1380

|

9

•

Solid fuels, in particular wood (in the form of chips, pellets or logs)

and mineral forms of solid fuel such as coal and coke.

•

Mains electricity (storage, immersion and portable room heaters).

•

Microgeneration technologies directly providing heat, in particular

ground source and air source heat pumps and solar thermal water

heating as well as biomass boilers or stoves that typically burn

wood.

•

Other microgeneration technologies that can indirectly generate heat

by producing electricity to operate heaters, in particular photovoltaic

panels and wind turbines.

2.4

The study focuses primarily on the supply of heating oil and LPG

because, apart from electricity which is already regulated by the Office

of the Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem) in Great Britain (GB) and the

Northern Ireland (NI) Authority for Utility Regulation (the Utility

Regulator) in NI, these are among the main energy sources for domestic

off-grid central heating.

2.5

The study considers whether the markets for these sources of domestic

energy are working well for consumers, taking into account both

competition and consumer issues.

2.6

The study also considers the potential role of alternative heating sources

such as microgeneration technologies, electricity and solid fuel. Our

initial interest in considering this arose because a wider cross-fuel choice

– if available – would create competitive pressures that could act as

important constraints on suppliers across all substitutable markets,

including heating oil and LPG.

2.7

However, our work has identified a limited degree of substitutability

among off-grid heating sources, primarily because of high switching

costs. In light of these costs, heating system replacement tends to be

infrequent and driven by major events such as housing changes or boiler

replacement.

OFT1380

|

10

2.8

Given the limited cross-fuel switching observed, off-grid energy

represents a collection of separate energy markets rather than a

cohesive market in its own right. Therefore, while there are some

themes common across these markets, it is appropriate to consider the

competition and consumer issues in each of these markets separately.

2.9

Accordingly, our report commences by describing the nature of the offgrid population and the common themes it faces. The report then

discusses each of the heating oil and LPG markets, which represent the

focus of our study, in more detail individually. We also include a

discussion of the microgeneration market which, despite not currently

representing a strong constraint on the heating oil and LPG markets due

to its small installed base, is of particular interest given its early stage of

development and hence potential for continued growth. A discussion of

other alternative energy sources is annexed to the study.

2.10

We conclude with a summary of our key findings and our

recommendations. We do not propose to refer the heating oil retail

distribution market to the Competition Commission and we are

consulting on this provisional non-reference decision.

Activities and data sources

2.11

In the course of our study we engaged with a wide range of relevant

parties: consumers; consumer organisations; industry representatives,

including trade associations and companies of diverse sizes; central,

devolved and local government; sector regulators; and interested third

parties including those with relevant sector expertise.5

2.12

Our evidence base was assembled by:

•

5

A call for submissions by the OFT at the time of the study launch,

following which a number of relevant parties provided submissions

and information to the OFT.

A list of key contributors to this market study is provided in Annexe P.

OFT1380

|

11

2.13

•

Data provided by industry following information requests by the OFT

to a sample of suppliers across the relevant industries.

•

Bilateral discussions and correspondence with relevant parties.

•

Eight roundtable sessions held across the UK (two in each nation) in

May and June 2011 bringing together a broad range of stakeholders

to contribute their experiences and views of the off-grid market.

•

Other correspondence with relevant parties.

The OFT also commissioned UK-wide consumer research from the

market research firm SPA Future Thinking (SPA). This comprised:

•

Qualitative research with off-grid consumers (8 focus groups and 46

depth interviews across the UK).

•

A quantitative survey with 400 heating oil consumers in the UK.

•

A mystery shopping exercise obtaining telephone quotes for heating

oil and cylinder LPG in locations across the UK as well as using a

sample of five heating oil websites.

A report by SPA on the consumer research findings is available on the

OFT website (the SPA Report).6

2.14

The OFT supplemented the above information through additional desk

research drawing on public and other third party data.

2.15

The remainder of this report summarises our findings from the above

discussions, research and analysis.

6

The SPA main report is published at: www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/market-studies/off-grid/finalreport.pdf. Data tables for the main report are published at: www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/marketstudies/off-grid/data-tables.pdf. Screener data for the main report are published at:

www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/market-studies/off-grid/screener-questions.pdf.

OFT1380

|

12

3

OVERVIEW OF THE OFF-GRID MARKET

Summary

3.1

This chapter considers the characteristics of the off-grid population

(meaning households not connected to the gas grid) and the common

issues they face. Our key findings are that:

•

15 per cent of UK households are off-grid, with large variation

between the four nations: 80 per cent of homes in NI are off-grid,

compared with only 12 per cent of homes in England. Proportionally

more off-grid households are single occupancy (in GB) and/or house

a person over the age of 60 (in the UK).

•

There are large urban off-grid populations in addition to rural off-grid

populations. In GB, electricity is the most common fuel for off-grid

households in urban locations; heating oil is most common in rural

locations. In NI, heating oil is the most common fuel regardless of

location.

•

The UK average cost of heating a typical three bedroom house is

around 50 per cent higher with heating oil and 100 per cent higher

with LPG than with mains gas. UK average heating costs for both

heating oil and LPG have risen over the last four years. Over this

period LPG has been consistently the most expensive and heating oil

has been the most volatile.

•

Switching between fuel sources is expensive and may make sense

only when boilers or central heating systems are replaced. Where

available, connection to the mains gas grid may be the best option.

In particular we note that 30 per cent of off-grid households in NI

may be within 50 metres of a gas connection. Microgeneration

technologies also represent an increasingly viable alternative. For

many households, however, improvements to home energy

efficiency may be the best way to improve affordability in the short

term.

OFT1380

|

13

3.2

This chapter sets out in more detail the characteristics of households off

the gas grid, and discusses the possibility of gas connections and the

wider context and issues for off-grid consumers.

Who is off-grid?

3.3

Around four million UK households are not connected to the mains gas

grid.7 This varies substantially across the UK, as shown in Table 3.1

below. Among the nations, NI has a unique majority reliance on non-gas

fuels since natural gas was only relatively recently introduced there in

1996. For more details of the derivation of Table 3.1, refer to Annexe A.

Table 3.1: Off-grid populations by nation

Mains gas

availability

England

Scotland

Wales

NI

UK

Off-grid

2,631

488

253

594

3,966

12%

21%

19%

80%

15%

('000

households)

Off-grid as a

percentage of

total

households

Sources: OFT analysis of Consumer Focus Report data; Welsh Government data; NI Utility

Regulator data and NI House Condition Survey 2009 data. Refer to Annexe A for more details.

3.4

Unless otherwise indicated, all off-grid statistics cited in the remainder of

this chapter8 are:

7

This is a conservative estimate, preferred as it is based on detailed breakdown figures

referenced elsewhere in the report. Other estimates range up to 4.7 million. Refer to Annexe A

for details.

8

Please note that the OFT has not undertaken any significance testing when referring to

statistical data from the Consumer Focus Report or the NI House Condition Survey. Differences

between groups are presented for information only and may not be statistically significant.

OFT1380

|

14

•

For GB – based on a report on off-gas issues to be published by

Consumer Focus9 (Consumer Focus Report) which draws on GB

survey data.10 A more detailed breakdown of differences by nation

within the GB data can be found in the Consumer Focus Report.

•

For NI – based on the closest comparable data, where available,

from the NI House Condition Survey 2009 published by the NI

Housing Executive.11

We caveat that neither of the above reports provides statistics that are

an exact match to our study definition of the off-grid population as set

out in paragraph 3.1. Hence, the off-grid statistics cited in this chapter

refer to the closest available proxy from the above and should be

understood as estimates. The relevant proxy is, for GB, the statistics for

homes that do not use gas as their main heating fuel12 and, for NI, the

9

Off-gas consumers: Information on households without mains gas heating, to be published by

Consumer Focus.

10

The Consumer Focus Report is based on analysis of data from the 2008 English Housing

Survey (EHS), the 2007/09 Scottish House Condition Survey (SHCS) and the 2008 Living in

Wales Survey (LIWS). The sample base for each survey is 15,523, 9,394 and 2,741 households

respectively. For more details, please refer to the Consumer Focus Report and Annexe A of this

report.

11

This survey is based on a sample base of 3,000 dwellings. Refer to

www.nihe.gov.uk/northern_ireland_house_conditions_survey_2009_-_main_report.pdf

Please note that some of the NI House Condition Survey 2009 statistics refer to dwellings and

some refer to households. In this report, where we refer to statistics from the NI House

Condition Survey, we have used both terms interchangeably, as where figures relating to

households are not available, figures relating to dwellings are the closest available proxy. For

example, the off-grid percentage of NI households presented in Table 3.1 is more precisely the

off-grid percentage of NI dwellings.

12

Not identical to our study definition, as some of these homes are, despite not using gas for

their main heating, connected to a gas supply.

OFT1380

|

15

statistics for households with non-gas central heating or no central

heating.13

3.5

The OFT definition of off-grid households, for the purposes of this study,

covers both homes that do not use gas but lie within a gas postcode14

('potentially connectable' homes with respect to gas supply) and homes

that do not use gas and do not lie within a gas postcode ('likely nonconnectable' homes). The possible circumstances and solutions for

households in each of these categories clearly differ and we will highlight

some of these differences in this chapter for interest.

3.6

The following figures show postcode areas that are not on the mains gas

grid – in each map these areas are outlined in black. We refer to these as

off-gas areas, which are likely to capture mainly the likely nonconnectable proportion of the off-grid population. We show these off-gas

areas overlaid against fuel poverty,15 rural and urban classification and

general deprivation indicators,16 in that order. This gives some idea of

where the off-grid population lives, how spread out it is and some

13

Not identical to our study definition for the following reasons. Categorisation is by use of gas

rather than connection to gas; and 'gas' includes LPG. Also, the data specify a particular off-grid

fuel usage only where this occurs with central heating systems; off-grid use of standalone

stoves or heaters is not broken down by fuel. Finally, a separate category of dual central heating

is identified which covers both gas fired and off-grid fuels. Where we do not have a breakdown

of dual central heating by type of fuel, we have excluded these households from the calculation

and state so in accompanying footnotes.

14

Defined as a postcode where at least some households within that postcode have been

recorded as having a gas supply.

15

For more details of the definitions of fuel poverty applied, which vary across the UK, please

refer to Annexe B. We note that for England, the fuel poverty definition and its associated

targets are currently being considered by an independent Review led by Professor John Hills.

Refer to: www.decc.gov.uk/en/content/cms/funding/fuel_poverty/hills_review/hills_review.aspx.

16

Because fuel poverty and deprivation are measured differently and at different points in time in

each nation of the UK, these maps are not directly comparable across nations. For example, the

most deprived area in England cannot be compared to the most deprived area in Wales.

OFT1380

|

16

indication of its likely vulnerabilities. Details of the sources for and

methodology underlying these maps are in Annexe B.

OFT1380

|

17

Figure 3.2: Map of UK off-gas areas by fuel poverty

Source: OFT mapping analysis based on Xoserve and other source data; refer to Annexe B

OFT1380

|

18

Figure 3.3: Map of UK off-gas areas by rural/urban classification

Source: OFT mapping analysis; based on Xoserve and other source data; refer to Annexe B

OFT1380

|

19

Figure 3.4: Map of UK off-gas areas by multiple deprivation indices

Source: OFT mapping analysis; based on Xoserve and other source data; refer to Annexe B

OFT1380

|

20

Off-grid rural/urban split and associated fuel use

3.7

In GB, there are clear differences in the off-grid population in urban

compared to rural locations. However, in NI, where the natural gas

market (introduced in 1996) is much less established, there remains a

prevalence of off-grid households across both urban and rural areas and

the differences between the two areas are less marked.

3.8

We therefore consider GB and NI separately below, making a distinction

between rural and urban locations only for the former.

GB

3.9

In GB, 51 per cent of off-grid households are in rural17 areas compared to

15 per cent of on-grid households. The higher than average rurality of

off-grid households reflects the higher costs of installing mains gas

infrastructure in such locations (due to, for example, the greater distance

to reach households, topological complexities and there being fewer

households over which to spread costs).

3.10

However, almost half of off-grid GB households are in urban areas.

•

This may in part be due to health and safety regulations prohibiting

mains gas from being installed in certain types of buildings.

Following the partial collapse of the high-rise Ronan Point apartment

building in London in 1968 due to a gas explosion, building

regulations were changed to ensure that new buildings over five

storeys tall were constructed to resist an explosive force such as a

gas explosion.18 Gas supply was banned from existing buildings that

17

Rural and urban definitions vary for each housing survey. For England and Wales, we have

estimated 'rural' data by combining the 'town and fringe', 'village' and 'hamlet and isolated

dwellings' categories.

18

www.pwri.go.jp/eng/ujnr/joint/35/paper/72lew.pdf

OFT1380

|

21

did not meet these criteria, resulting in a number of high rise blocks

switching to electricity.

•

3.11

Some landlords may also be unwilling to take on onerous gas

installation and maintenance regulations.19

Because of the different circumstances affecting the urban and rural offgrid populations as described above, the two populations are also quite

distinct in nature, with substantial differences in particular with respect

to the types of fuels used. This is illustrated by Figure 3.5 which show

the use of different off-grid fuels in urban and in rural areas:

•

Urban off-grid households rely largely on electricity (90 per cent use

this as their main heating fuel in GB). The reasons set out above are

likely to factor into this. Other possible reasons include:

-

Flammable and contaminable fuels with relatively high levels of

emissions are less favoured (or may not be allowed by regulation20) in

densely built up areas and are also less easy to deliver door-to-door

given the size of the delivery vehicles.

-

Urban homes are also less likely to have the outdoors space available

to accommodate storage tanks or solid fuel stockpiles.21

19

Based on discussions with some stakeholders. For details of applicable regulations, refer for

example to: www.letlink.co.uk/letting-factsheets/factsheets/factsheet-7-the-gas-safetyinstallation-and-use-regulations-1998.html

20

Under the Clean Air Act 1993 and the Clean Air (NI) Order 1981, smoke control areas have

been introduced in many large towns and cities in the UK and in large parts of the Midlands,

North West, South Yorkshire, North East of England, Central and Southern Scotland. In these

areas, it is an offence to emit smoke from a chimney of a building, from a furnace or from any

fixed boiler. (Source: smokecontrol.defra.gov.uk/background.php#smoke)

21

This seems a reasonable general assumption but, for illustration, the English Housing Survey

Housing Stock Summary Statistics Tables, 2009, show that the average floor area for a dwelling

in a city centre is 71 square metres compared to 153 square metres in a rural area. Refer to

Table SST1.1 in www.communities.gov.uk/documents/statistics/xls/1937429.xls

OFT1380

|

22

•

Rural off-grid households have fewer such constraints and rely much

more on delivered fuels, in particular heating oil which is the main

heating fuel for 53 per cent of GB rural off-grid households.

Figure 3.5: Main heating fuel by location and nation for GB off-grid

households

Rural

100%

100%

90%

90%

80%

80%

70%

70%

% off-grid households

% off-grid households

Urban

60%

50%

40%

30%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

20%

10%

10%

0%

0%

England

Scotland

Wales

LPG & Bottled Gas

Solid Fuel

England

Scotland

Wales

Heating Oil

Electric heating

Source: Consumer Focus Report22

3.12

As shown in Figure 3.5, there are also considerable variations by nation.

Notably, the proportion of off-grid households using electricity is lower in

Wales than elsewhere in GB, in both urban and rural areas. Conversely

the proportion of off-grid households using heating oil or solid fuel is

higher in Wales than elsewhere in GB, in both urban and rural areas

(although the difference is less marked in the latter).

22

For urban areas, the number of households is 1606 (England), 288 (Scotland) and 40 (Wales

– note the small size). For rural areas, the number of households is 1509 (England), 253

(Scotland) and 229 (Wales).

OFT1380

|

23

3.13

A clear majority of GB off-grid households rely on a mix of fuels to heat

their home (80 per cent use secondary fuels, with the figure higher

among households using heating oil and LPG as their main fuels and

lower among households using electricity as their main fuels). The SPA

research corroborated that a high level of secondary use exists, with 75

per cent of GB heating oil consumers surveyed using a secondary

heating fuel. Mains electricity (which we assume means portable

heaters) and/or23 wood were each used by around 40 per cent of GB

heating oil consumers, followed by coal/coke (25 per cent) and cylinder

LPG (seven per cent).

NI

3.14

In NI, a clear majority (around 80 per cent) of the population is off-grid.24

78 per cent of urban households are off-grid and 99 per cent of rural

households are off-grid.

3.15

About two-thirds of all NI households (68 per cent) use heating oil as

their primary heating fuel,25 rising to 81 per cent of off-grid households.

Electricity heating – used by five per cent of off-grid NI households – is

much less common in NI than in GB and is associated mainly with urban

areas and apartment buildings.26

23

Respondents could select multiple responses in this question.

24

Please note that the percentage of off-grid households derived from NI House Condition

Survey 2009 data (84 per cent) differs slightly from the percentage of off-grid households in

Table 3.1 (80 per cent). We assume this may be because some households with a gas supply do

not use it for central heating.

25

NI House Condition Survey 2009, data provided by the NI Housing Executive. Please note that

fuel use is recorded according to central heating (CH) type and there may be additional oil, solid

fuel or electricity use within the categories CH Dual/Other and Non CH.

26

According to the NI House Condition Survey 2009 Report: ' … over two-thirds (67%) of all

dwellings with electric central heating were flats/apartments … The majority of dwellings with

electric (92%) central heating were located in urban areas, partly reflecting concentrations of

OFT1380

|

24

Table 3.6: NI off-grid fuel use by location

% of off-grid households

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

All

CH Oil

CH Solid Fuel

Urban

CH Electricity

Rural

CH Dual/Other

Non CH

Source: NI House Condition Survey 2009. Note that 'CH' refers to central heating.

3.16

The SPA research showed that a high level of off-grid secondary use

exists, with 65 per cent of NI heating oil consumers surveyed using a

secondary heating fuel. Mains electricity (which we assume means

portable heaters) and/or27 coal/coke were each used by around 30 per

cent of NI heating oil consumers, followed by wood (20 per cent) and

cylinder LPG (14 per cent). This suggests that, among heating oil

consumers, coal/coke is preferred to wood as a secondary solid fuel in NI

whereas this is reversed in GB; and secondary cylinder LPG use is also

higher in NI than in GB.

Off-grid housing stock

3.17

Off-grid households face some particular challenges in respect of housing

stock, which may make off-grid housing on average harder to treat.

Housing Executive dwellings.'

www.nihe.gov.uk/northern_ireland_house_conditions_survey_2009_-_main_report.pdf

27

Respondents could select multiple responses in this question.

OFT1380

|

25

3.18

3.19

3.20

Off-grid households generally seem to be less energy efficient:

•

In GB, 59 per cent of off-grid households (mainly electricity users)

do not have central heating as their main heating system. However,

this is not similarly a factor in NI where less electric heating is used.

•

A higher proportion of GB off-grid households have the lowest F and

G Energy Performance Certificate (EPC)28 ratings (49 per cent

compared to 10 per cent on-grid). Similar data were not readily

available for NI.

Among those who are off-grid in Scotland and Wales, and within

segments of this population in England, there is on average a higher

proportion of households with solid wall construction – which indicates

that these households will less readily be able to reduce their energy

needs through cavity wall insulation. Similar figures are not available for

NI.

•

In Scotland and Wales respectively, 28 per cent and 34 per cent of

off-grid properties have solid walls compared to 20 per cent and 26

per cent of on-grid properties.

•

In England, data from the English Housing Survey suggest that the

incidence of solid walled properties is greater in more remote areas

(hamlets and isolated dwellings).

Households living in rental accommodation are at a further disadvantage

in terms of energy use, as they have less control over improvements to

their housing stock. On average, a slightly higher proportion of GB offgrid households are in rental accommodation compared to GB on-grid

households (38 per cent compared to 31 per cent). However, this differs

28

'Every home which has been on the market should have an Energy Performance Certificate

(EPC) which rates the home for energy efficiency. Energy Performance Certificate Ratings run

from A (very efficient) to G (very inefficient). The average rating in the UK at the moment is D.'

Source: www.energysavingtrust.org.uk/Home-improvements-and-products/Moving-home-agreen-guide

OFT1380

|

26

by nation: notably, in Scotland the difference is more marked (46 per

cent to 34 per cent). In Wales the position is reversed (21 per cent to 28

per cent). Similarly, in NI, a higher proportion of off-grid households own

their homes (66 per cent) than on-grid households (45 per cent).29

Off-grid demographics

3.21

When comparing the income distribution for off-grid households

compared to on-grid households, the picture across the different nations

is mixed. Each nation presents income distributions in a slightly different

way and so they cannot be directly compared with each other. Broadly,

however, there appears to be variation in the income profiles for

households using different off-grid fuels.30

3.22

Notwithstanding this, a higher proportion of GB off-grid households are

in fuel poverty31 (32 per cent, compared to 15 per cent of on-grid

households; while NI experiences the highest levels of fuel poverty in the

UK32 at 44 per cent overall33). This implies that features of the housing

29

These NI figures are calculated excluding dual fuel use.

30

In GB, a higher than average proportion of solid fuel and electricity consumers are in the

lowest three income bands surveyed and a higher than average proportion of heating oil

consumers are in the highest three income bands surveyed. Refer to the Consumer Focus Report

for more details of the GB statistics. In NI, 25 per cent of off-grid households in the top income

bracket recorded earn more than £30,000, compared to 17 per cent for on-grid households.

31

The definition of fuel poverty varies slightly across the nations. Please refer to Annexe B for

more details; however for example in England: 'A household is said to be in fuel poverty if it

needs to spend more than 10% of its income on fuel to maintain a satisfactory heating regime

(usually 21 degrees for the main living area, and 18 degrees for other occupied rooms)'.

(www.decc.gov.uk/en/content/cms/statistics/fuelpov_stats/fuelpov_stats.aspx)

32

As cited on page 5 of DETINI's 2010 Strategic Energy Framework.

33

No corresponding data for the off-grid and on-grid segments are readily available from the NI

House Condition Survey. However, 46 per cent of rural NI households are in fuel poverty

compared to 43 per cent of urban NI households and 99 per cent of rural households are offgrid. Furthermore, according to the 2009 NI House Condition Survey Report (page 63), NI

households using off-grid central heating fuels such as electricity or solid fuel have higher levels

OFT1380

|

27

stock and the relatively higher costs of off-grid fuels as shown later in

Figure 3.7, together clearly affect the average energy spend of an offgrid household.

3.23

Among off-grid households (comparable NI statistics are only shown

where of interest):

•

A higher proportion of GB off-grid households are single occupancy

(41 per cent compared to 27 per cent on-grid) although in Wales

there is no substantial difference (26 per cent compared to 25 per

cent on-grid).

•

A higher proportion of GB off-grid households house a person over

the age of 60 (22 per cent compared to 15 per cent on-grid). The

same applies in NI, where 31 per cent of off-grid households house a

person aged 60 years or older, compared to 21 per cent of on-grid

households.34

•

A lower proportion of GB off-grid households house a couple with

dependent child(ren) (15 per cent compared to 23 per cent on-grid).

The first two cases may be more vulnerable to fuel-related concerns, for

example because those in older age groups are more likely to be in

retirement with fixed incomes.

Switching across off-grid fuels

3.24

This section considers the potential benefits to households from

switching between off-grid energy alternatives and the extent to which

barriers to switching may exist. Our analysis of potential benefits

focuses on costs, because the SPA research and the correspondence we

have received both indicate that costs are a major concern for off-grid

of fuel poverty (69 per cent and 63 per cent respectively) than households using heating oil and

mains gas central heating (41 per cent and 43 per cent of whom are fuel poor respectively).

34

These NI figures are calculated excluding dual fuel use.

OFT1380

|

28

consumers and a main driver of their purchasing behaviour. But we

recognise that myriad other factors such as environmental

considerations, ease of handling and ease of buying also affect

household fuel choices.

3.25

Off-grid fuels are generally a more expensive option than gas. This is

illustrated by Figure 3.7, which uses data from Sutherland Tables35 to

illustrate the comparable costs for heating an average-size threebedroom house with different types of fuel.36

•

For example, in July 2011, the latest period for which comparable

data is available from Sutherland Tables, the UK average cost37 of

heating an average-size three-bedroom house was 47 per cent higher

for oil and 107 per cent higher for LPG, in each case compared to

gas.

35

Information about Sutherland Tables can be found on their website:

www.sutherlandtables.co.uk

36

This is based on data from Sutherland Tables that are 'intended to be used to compare

different domestic fuels and the costs of using them under similar conditions. Their primary

purpose is not the prediction of actual operating costs in any particular dwelling, although they

will of course give an indication of this' (Sutherland Tables, Introduction to the July 2011

Tables).

37

For consistency with Figure 3.7, where calculating UK averages based on Sutherland Tables

data in this report, we have followed Sutherland Tables's methodology of a simple average

across the six UK regions (South East, South West and Wales, Midlands, Northern England,

Scotland and NI) for which they provide cost data.

OFT1380

|

29

Figure 3.7: Comparative Domestic Heating Costs – United Kingdom

National Averages, July 2011

Source: Sutherland Tables, July 2011

3.26

Data from Sutherland Tables show that, among the fuel types shown,

the costs of all fuels, but in particular of LPG and of heating oil, have

risen over the past four years. In this period, LPG has been consistently

the most expensive off-grid option followed by, on average, heating oil

which has been the most volatile in terms of costs. However, we note

OFT1380

|

30

that the comparable heating cost based on a standard electricity tariff38

exceeds the costs of both LPG and heating oil.39

3.27

There is also variation in heating costs by region, as would be expected

in light of temperature differences. Scotland is the most expensive

region while the South-West of England and Wales40 appears to be the

least expensive region, for most fuels. However, '… sometimes these

variations are not systematic in terms of climate. For example, heating

and hot water costs with wood pellets are much cheaper in NI than in

Scotland or the North of England, while figures for solid fuels are

cheaper in South West England and Wales than in the South East of

England. In these cases, local economics appear to prevail over climate

conditions.'41 In our view, the differences may also reflect geographic

features leading to higher establishment and transportation costs for

supplying the relatively higher number of outlying areas in Scotland

compared to other UK nations. For NI, the Sutherland Tables data42 also

show that:

•

Standard gas heating costs appear higher in NI than in GB, so that

the cost disadvantage of being off-grid is reduced for the former –

particularly as the NI heating costs for heating oil, which is used by

the majority of off-grid households, are also lower than in GB.

38

According to the SPA research, a standard electricity tariff, rather than more economical

special tariffs like Economy 7, is used by a minority of the off-grid households sampled who use

electricity for heating. These sampled households should be seen as representative of electricity

use only in the areas surveyed. Further details are provided in the screeners to the SPA Report.

39

Heating costs using standard electricity to run radiators (rather than storage heaters) were one

per cent higher than the heating costs using LPG based on a UK average from Sutherland Tables

data for July 2011.

40

Costs for the South West of England and Wales are not reported separately and are

represented only as a combined cost in Sutherland Tables's standard cost tables.

41

Sutherland Tables: Commentary on April 2011 Tables.

42

Sutherland Tables, July 2011 data.

OFT1380

|

31

•

NI heating costs for some solid fuels and for electricity have risen

less relative to the four-year average than in other regions (and

indeed, for wood pellets, have reduced).

3.28

The wide range and variability of off-grid fuel costs observed shows that

the mix of fuels used can have a significant impact on heating costs for

the average off-grid household. This suggests that some off-grid

households could benefit from switching to another off-grid fuel.

3.29

To illustrate this, Table 3.8 summarises, for each off-grid heating source:

•

The relative estimated upfront costs of installation.

•

The annual savings relative to heating oil.

OFT1380

|

32

Table 3.8: Relative upfront and heating costs of off-grid fuels

LPG43

Microgeneration

Solid fuels

Electricity

Upfront costs £3.5k (installation

£8k44

and

equipment)

£2.5k £6k45

Wide range depending

on technology but

typically between £2k

- £23k

c. £0.5k£7k46

c. £2k47

Average

annual

heating costs

relative to

heating oil

+41%

-100% to -54%

-22% (wood

pellets)

-22%

(economy)

-23% (coal)48

+42%

(standard)

Heating

oil

-40%

(anthracite)49

Source: OFT research and supplier estimates. Information on the relative costs of

microgeneration technologies can be found on the EST website.50 Other average relative heating

costs are calculated by the OFT from Sutherland Tables data for July 2011, for an average size

three-bedroom house in the UK, and assuming the use of conventional boilers for oil and LPG.

43

The annual savings figures provided relate to bulk LPG, which suppliers have informed us

tends to be more economical than cylinder LPG.

44

www.homeheatingguide.co.uk/central-heating-cost.html

45

www.homeheatingguide.co.uk/central-heating-cost.html

46

OFT desk research and information provided by the Solid Fuel Association.

47

See www.energysavingtrust.org.uk/business/Business/Housing-professionals/Interactivetools/Hard-to-treat-homes/Matrix/Electric-storage-heating and

www.energysavingtrust.org.uk/business/Business/Housing-professionals/Interactive-tools/Hardto-treat-homes/Matrix/Explanation-of-terms-used

48

Housecoal gp A(1).

49

In the form of peas / grains.

50

www.energysavingtrust.org.uk

OFT1380

|

33

3.30

We note, however, that Figure 3.7 and Table 3.8 provide a historic view

of annual heating costs that may change over time depending on the

relative development of the different sectors. For example, while heating

costs using oil are currently more expensive than heating costs using

electricity, when averaged over a four-year period these costs have, at

least in some nations (Scotland and NI) been on a par;51 and going

forward, gas and electricity suppliers have recently announced

substantial increases in their standard rates. 52 Furthermore, a

comparison of whole-life costs taking into account potential differences

in upfront costs, average replacement life cycles and average

maintenance costs among different heating systems may yield different

outcomes for different households depending on their individual

circumstances than a comparison of relative annual running costs.

3.31

We also note that cost is only one factor in a household's determination

of the best off-grid heating source for its circumstances – ease of use,

quality of heat, emissions, efficiency and security of supply are examples

of other factors that may be relevant. Different fuel types offer quite

diverse purchasing and usage experiences, so that consumers would

need to research the features of different options, the availability of local

suppliers and other relevant factors carefully to determine which type is

most suitable for their individual circumstances before taking any

decision to switch.

3.32

In any case, the possible cost or other benefits that may derive from

switching between different heating sources, including as a result of

51

Sutherland Tables data, July 2011.

52

For more information refer to:

www.decc.gov.uk/en/content/cms/meeting_energy/markets/making_energy_/making_energy_.as

px

www.uregni.gov.uk/news/utility_regulator_comments_on_power_ni_tariff_announcement

www.uregni.gov.uk/news/increases_in_international_fuel_costs_directly_responsible_for_the_gas

_price_rise_announced_by_phoen

OFT1380

|

34

increasing competition and choice across the market for off-grid fuels as

a whole, are only available where switching is readily feasible.

3.33

This is not the case for off-grid consumers, as our study has identified

considerable barriers to switching between different fuel types.

3.34

These barriers largely arise because such a switch typically requires the

replacement of the boiler and central heating system. The upfront cost

of installing a new central heating system throughout the home is

generally the main barrier to switching. However, the disruption that this

would entail, given that the system is often embedded in the

infrastructure of the building to some extent, is also a strong deterrent.

•

Other barriers relate to lack of information and awareness about

different fuels and their relative costs.

•

In some cases (for example in rental accommodation), consumers

are constrained by having little choice over the form of heating used.

•

In some cases, bulk LPG consumers can face additional fuel

switching costs related to charges for the removal of their LPG

storage tank where this is owned by their supplier.

3.35

Accordingly, off-grid opportunities to switch fuel type tend to be eventdriven: for example, by changes in housing circumstances (moving

home, or refurbishment), or aligned with the life cycle of a boiler (around

12 years).53

3.36

Replacement in the latter case tends to arise only when the heating

system breaks down, which by nature represents a distressed situation

in which a household may make a replacement decision more for reasons

of expediency (in which case a like-for-like replacement is most

straightforward and therefore probable) than long-term efficiency.

Households may also be guided in their decision-making at such times by

53

www.energysavingtrust.org.uk/Home-improvements-and-products/Heating-and-hot-water

OFT1380

|

35

the person servicing their existing boiler, who may not have experience

of or access to alternative solutions.

3.37

The odds are therefore stacked against fuel switching in that

opportunities to do so are generally rare, and constrained even when

they arise.

3.38

The existence of significant barriers to switching in practice is borne out

by the fact that many of those households who use heating oil appear to

have done so for a very long time. The SPA survey of heating oil

consumers, for example, showed that 63 per cent of UK heating oil

consumers surveyed have used heating oil for over 10 years (rising to 78

per cent for NI consumers alone) and for the majority54 of all UK heating

oil consumers surveyed this had been ever since moving into their home.

3.39

In light of the difficulties in switching between different types of off-grid

heating sources, we conclude that off-grid energy is not in fact a market

in its own right but, rather, represents a community who share the

common feature of not being connected to the mains gas grid, albeit

that they are consumers in largely separate markets.

3.40

Given that switching costs limit substitutability between heating

sources, we have considered the different off-grid fuels separately.

Therefore the next chapters of our report consider each of the heating oil

and LPG markets in turn and separately from any other. The report also

considers the microgeneration market which, despite not currently

representing a strong constraint on the heating oil and LPG markets due

to its limited off-grid installed base, is of interest given its relative

immaturity compared to the other off-grid fuel markets and hence

potential for rapid growth.

54

73 per cent of GB consumers and 61 per cent of NI consumers.

OFT1380

|

36

3.41

Our findings in respect of the electricity55 and solid fuel markets for

heating use, which the study has also considered in the limited context

of their role as possible alternatives to heating oil and LPG, are attached

in Annexes M and N respectively.

Gas connection as an off-grid option

3.42

Connection to the mains gas grid may be an attractive option where

available. Natural gas is a relatively low carbon56 energy source that is

easy to use and offers greater security of supply than fuels requiring

road transportation to the home. A choice of suppliers is available and its

status as a regulated sector affords the consumer additional protections.

It also has the advantage of being – at least in recent times57 – a

relatively inexpensive source of space and water heating.58

3.43

The potential for expansion of the grid differs between GB and NI. In GB:

•

The option for large scale expansion of the mains gas grid was

previously considered in 2001 by a working group chaired by the

then Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). The report of the

working group (the DTI Report)59 found that, even were a full-scale

extension of the gas network possible, it would not be justified on

cost/benefit grounds.60 Furthermore, at an individual level, while

55

Although electricity is used for heating by a large proportion of off-grid households, we have

not focused on the supply of electricity within this market study as this is separately regulated.

56

Natural gas is the lowest polluting fossil fuel (source: NI Strategic Energy Framework 2010).

57

As noted, there is no certainty about how the relative costs of different off-grid fuels may

develop in future.

58

Refer to Figure 3.7.

59

Report of the Working Group on Extending the Gas Network, 2001.

60

Report of the Working Group on Extending the Gas Network, 2001. The report refers to an

estimated cost of £80m to connect 100 communities.

OFT1380

|

37

connection to the gas grid may be the most appropriate solution for

a given household, it is not necessarily so in every case and a wide

range of other (sometimes quicker) options should be taken into

account.

•

Small-scale extension of the GB gas grid is still occurring on an adhoc basis, funded either by the individual household or community

requesting the connection, or through the Fuel Poverty Scheme

administered by Ofgem (as described in more detail in Annexe D).

New gas connection levels have been falling over the past few

years, with around 78,000 gas connections to GDN owned

networks in 2009/10, down from 114,000 in 2007/08.61 78,000

represents approximately two per cent of the estimated size of the

GB off-grid population.

3.44

In NI, the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (DETINI) has

consulted on the potential for extending the natural gas network.62 The

consultation closed only recently, on 30 September 2011, so no decision

has yet been made. Even without expansion, the relatively recent

introduction of natural gas in NI means that many off-grid households

could be, but have not yet been, connected – as detailed below.

3.45

Without further large scale expansion, our work has estimated that

(depending on the criteria used) between five and 45 per cent of off-grid

households by nation are currently potentially connectable63 to the mains

61

Refer to Table 2.5 of Ofgem's Gas and Electricity Connections Industry Review 2009-10, 28

March 2011. The Review is published at:

www.ofgem.gov.uk/Networks/Connectns/ConnIndRev/Documents1/CIR%2009-10.pdf

Paragraph 2.22 explains that GDN networks account for a much higher proportion of

new/modified connections to existing domestic premises.

62

The consultation may be viewed at: www.detini.gov.uk/deti-energy-index.htm

63

A further (approximately) 500,000 GB households are connected to a mains gas supply but do

not use it as their main heating source. As these households fall outside our off-grid definition,

we will not consider them further in the context of this study. However, as a potentially readily

OFT1380

|

38

gas grid. Our definition of connectable relates to location relative to the

mains gas grid. It is, as such, a technical measure rather than one based

on affordability; furthermore it does not take into account feasibility

(such as geographical, geological or engineering factors). Our analysis is

set out in Table 3.9 – more details are provided in Annexe A.

Table 3.9: Estimates of the percentage of off-grid households that

are potentially connectable based on proximity to the mains gas grid

England

Wales

Scotland

NI

Potentially

connectable

(within 50 m)

N/A

6%

N/A

30%

Potentially

connectable

(within 1 or 2

km)

20% (Southern

Gas Network

only, 2 km)

31% (1 km)

40% (2 km)

N/A

Potentially

connectable (in

gas postcode)

42%

22%

35%

N/A

Source: OFT analysis of Consumer Focus Report, Scotia Gas Networks data and NI Utility

Regulator data; Welsh Government analysis

3.46

A lower distance from the grid implies a greater likelihood of

connectability.64 Table 3.9 shows that the largest opportunity for gas

connections is in NI, where a material proportion of off-grid households

addressable subset of those households who may struggle with non-gas heating costs, this

segment may be of particular policy interest. We refer interested parties to section 2.6 of the

Consumer Focus Report which analyses this segment (in England) in more detail.

64

The exact distance beyond which connection costs are not practical will vary according to

dwelling density and technical factors among others, but two km is one proxy that has been

used in some analyses (Scottish House Condition Survey, Scotia Gas Networks) as an indicative

threshold.

OFT1380

|

39

live within 50 m where connection is currently generally free,65 more

cost-effective (hence affordable) and more likely to be feasible.

3.47

Although, from Table 3.9, the potentially connectable proportion of the

off-grid population appears at face value substantial, it must be

emphasised that engineering feasibility has not been taken into account

in this analysis. Furthermore, analysis of this segment reveals inherent

characteristics that may reduce their actual connection opportunities:

•

For example, many of the GB households who are theoretically

connectable are, in practice, unable to connect to the gas grid due to

location, 66 tenure67 or housing stock68 restrictions that are also likely

to explain their higher reliance on electric heating.

•

In NI, we expect the potentially connectable population to be

concentrated in the urban areas where the current gas network

areas are located; more detailed data on this segment are

unavailable. Nevertheless, constraints on connection are likely to be

fewer than in GB as a higher proportion (66 per cent) of the NI off-

65

firmus energy will connect households within 30 metres and Phoenix Gas Networks will

connect households within 50 metres. Refer to Annexe D for more details.

66

In GB, a higher proportion of the potentially connectable segment are located in urban areas

(75 per cent) compared to the likely non-connectable segment (26 per cent) with there being

less of a difference in Wales. Refer to Annexe C for more details.

67

In GB, more households that are potentially connectable are renting (44 per cent) compared to

those that are likely non-connectable (34 per cent). The proportion of potentially connectable

households in rental is notably higher than average in Scotland (58 per cent) and lower than

average in Wales (26 per cent). Refer to Annexe C for more details.

68

The proportion of those in flats among potentially connectable households was higher for

England and Wales (44 per cent and 13 per cent respectively) than for likely non-connectable

households (23 per cent for England and five per cent for Wales). In Scotland there was no

difference between the two groups. Refer to Annexe C for more details.

OFT1380

|

40

grid population owns their home and a lower proportion lives in flats

or apartments (six per cent).69

3.48

69

Besides feasibility considerations as covered above, there are also, in

practice, other more general yet equally substantial barriers to

connection. Consistent with the overall barriers to fuel switching

described in paragraphs 3.34, these are primarily concerned with costs,

disruption and awareness. The disruptive effects are self-evident; the

other points are discussed below:

•

The average cost of connection for an individual household

sufficiently close to the mains gas grid to benefit from regulated

connection charges and acting independently of others, where the

engineering requirements are straightforward, is in the region of

£660 per GB household70 and, in NI, is free where a dwelling is

within 30 or 50 metres of the grid.71 However, the large majority of

households will incur bespoke costs that can vary widely upwards of

this depending on factors including distance from the closest

suitable gas mains access point and complexity of installation.

•

Connection costs are in addition to the costs of installing a gas boiler

and associated pipework (up to around £2,000 depending on the

complexity of the installation)72 and the cost of the boiler itself (in

the region of £1,000).73

These NI figures are calculated excluding dual fuel use.

70

Please refer to Annexe D for details of gas connection costs. Average is calculated as a

straight average of connection charges that include the cost of backfill by the GDN.

71

Depending on the relevant NI gas network area.

72

See for example: www.which.co.uk/home-and-garden/heating-water-andelectricity/guides/installing-a-boiler/

73

www.energychoices.co.uk/partner-lp_do-you-need-a-new-boiler/do-you-need-a-newboiler.html#5

OFT1380

|

41

•

3.49

3.50

Consumers may not be sufficiently aware of their proximity to the

gas grid, the cost and process of connection, or available financial

support (as described in Annexe D), to properly assess their options

for connection. The SPA research found that such awareness within

the sample of off-grid consumers providing qualitative feedback

appears low. Government, regulators and/or industry may therefore

wish to consider means of raising awareness, particularly of

available connection funding, within qualifying off-grid households.

In summary, our analysis of potential connectability among the off-grid

population concludes that:

•

There are many factors that will in practice significantly limit the

achievable conversion rate among those households who have an

opportunity to do so. However, there should still be numerous

households for whom connection is a genuine option for

consideration.

•

Nevertheless, it should also be recognised that this option is

primarily one available to urban off-grid households and therefore

offers little if any relief for the many off-grid consumers who live in

rural areas. This is both because the majority of potentially

connectable households are located in urban areas and because of

scale efficiencies in incurring connection costs that favour urban

areas.74

For NI, there are further differences that should be noted. Here, more so

than in other nations of the UK given the relative immaturity of the NI

natural gas market, there is a significant opportunity to decrease the size

of the off-grid population either by expansion or by increased conversion

to natural gas within existing grid areas. Both are consistent with

74

All else equal, mains gas extension is most economic where there is a greater density of

connectable households within a certain distance from a grid, to share the predominantly fixed

costs of laying an extension. Therefore, any gas extension programme that seeks to maximise

cost-effectiveness is likely to focus on urban rather than rural areas.

OFT1380

|

42

DETINI's stated objectives to promote opportunities for switching to

lower carbon fuels such as natural gas and biomass, where it is cost

effective to do so,75 which will also assist in alleviating the high fuel

poverty levels in NI.

3.51

Nevertheless it is clear that there are strong barriers to the adoption of

gas by NI consumers, even where already available, including high levels

of satisfaction with existing home heating and the need to reassure a

nervous public with limited experience of gas of its safety and to

effectively communicate its benefits.76

3.52

We therefore support the plans set out in the 2010 Strategic Energy

Framework published by DETINI77 to '(a)gree a strategy to incentivise

gas connections and increase gas uptake in existing and future licensed

areas'. As illustrated, there seems to be potential for such a programme

to have a strong impact in NI, which represents 15 per cent of all UK

off-grid households.

The wider off-grid landscape

3.53

75

This section provides some further general context, as background for

the consideration of off-grid issues in this report, on the wider policy and

regulatory support and energy measures that may be relevant to off-grid

consumers.

www.detini.gov.uk/strategic_energy_framework__sef_2010_-3.pdf

76

A study undertaken by Action Renewables and Element Energy on behalf of the Energy Saving

Trust (Into the West: Low carbon heat options off NI's gas network, July 2010) found that

among those uninterested in the potential of connecting to gas, almost two thirds (64 per cent)

felt there was nothing that could be done to help them change their mind, although as expected

the level of interest increased where the availability of grants was factored in. The SPA research

found that only nine per cent of NI heating oil consumers surveyed who could access gas said

they were likely to do so within the next three years. (Please note that this finding is based on a

small sample size of 47 NI consumers who could access gas.)

77

Refer to: www.detini.gov.uk/strategic_energy_framework__sef_2010_-3.pdf

OFT1380

|

43

Policy support

3.54

The UK Government and Devolved Administrations are committed to

supporting increased energy efficiency and promoting low carbon

energy.

•

-

The flagship policy in the Bill is the 'Green Deal', a scheme whereby

householders, private landlords and businesses would be given

finance upfront to make energy efficiency improvements, which

would then be paid for from energy bill savings. The Green Deal will

be introduced from October 2012.

-

The Bill also seeks to establish a new Energy Company Obligation

(ECO),79 which will take effect from the end of 2012 and places

requirements on energy companies to help certain groups of

consumers who are more exposed to energy issues. ECO works

alongside the Green Deal by targeting appropriate measures at those

households which are likely to need additional support, in particular

those containing vulnerable people on low incomes and those in hard

to treat housing. ECO replaces existing obligations to reduce carbon

emissions (the Carbon Emissions Reduction Target (CERT) and

Community Energy Saving Programme (CESP)), which expire at the

end of 2012.

•

78

For GB, the Energy Bill 201178 includes the following elements:

Alongside this, the Welsh Government has published an Energy

Policy Statement on its ambitions for a Low Carbon Revolution80 and

www.decc.gov.uk/en/content/cms/legislation/energy_bill/energy_bill.aspx

79

By amending existing powers in the Gas Act 1986, Electricity Act 1989 and the Utilities Act

2000.

80

wales.gov.uk/topics/environmentcountryside/energy/renewable/policy/lowcarbonrevolution/?lang

=en

OFT1380

|

44

the Scottish Government's Low Carbon Economic Strategy forms an

integral part of its overall Economic Strategy.81

•

For NI, DETINI's 2010 Strategic Energy Framework aims for an

energy system where 'much more of (NI's) energy is from renewable

sources and the resulting economic opportunities are fully exploited;

and energy efficiency is maximised'.82

•

The Devolved Administrations are also active through schemes

including arbed and Nyth/NEST in Wales, the Energy Assistance

Package in Scotland83 and Warm Homes in NI. In England, similar

funding is available through the Warm Front scheme. More details of

these schemes are set out in Annexe L.

3.55

The UK Government and Devolved Administrations are also implementing

specific initiatives related to microgeneration takeup (for example the

Renewable Heat Incentive programmes in GB and in NI, and Feed-InTariffs in GB) that are described in more detail in Chapter 6.

3.56

The measures highlighted above are applicable to both on-and-off-grid

households. However, existing and proposed measures mostly do not

distinguish between off-grid and on-grid targets or specific fuel types.

•

81

Off-grid households are a notable segment of the relevant population

for, and can benefit significantly from, these policies, given the fuel

types used, the limited alternatives available and the harder-to-treat

nature of a substantial proportion of the housing stock.

www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Business-Industry/Energy/Action/lowcarbon

82

DETINI Strategic Energy Framework, September 2010

www.detini.gov.uk/strategic_energy_framework__sef_2010_-3.pdf

83

The Energy Assistance Package is one of a range of fuel poverty and energy efficiency

schemes to which the Scottish Government has announced in October 2011 a 35 per cent

increase in overall funding. www.scotland.gov.uk/News/Releases/2011/10/05163256

OFT1380

|

45

•

Our analysis shows that the issues faced by off-grid households

differ to some extent from those faced by on-grid households, and

indeed differ even between off-grid households in urban and in rural

areas, hence potentially warranting distinctions within policy.

3.57

Absent such distinctions, there may not automatically be intervention to

the degree that may be desirable among the off-grid population – in

particular the large proportion of this population that is located rurally –

given asymmetries that may exist in the costs and challenges of rolling

out such measures to different groups or areas or for specific fuel types.

3.58

Should policy intervention be considered, Government may therefore

wish to consider whether the introduction of policies targeted