Calhoun the Political Philosopher

advertisement

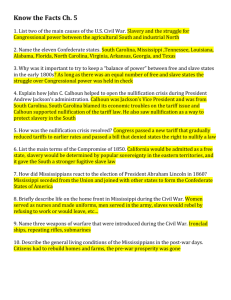

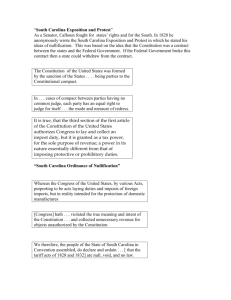

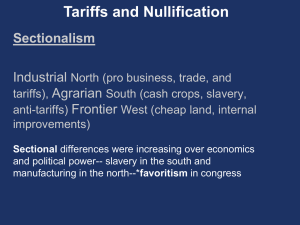

Calhoun the Political Philosopher JOSEPH KELLY Rollins College John C. Calhoun’s name is probably the one most associated with the doctrine of nullification. This could be for a number of reasons. Perhaps it is because, as vice president of the United States, he was the highest-ranking government official to side with the nullifiers. Perhaps it is because he penned the original drafts of the famous “South Carolina Exposition” and “Protest,” which so eloquently defended the doctrine. Perhaps it is because he, more than anyone, worked to convince outsiders of nullification’s intellectual merit; as William Freehling put it, “after working with the theory for a time, his commitment came closer to resembling an author’s pride in his own artistic achievement.”1 Despite Calhoun’s close association with nullification, however, he should not be credited with creating the doctrine. That distinction goes to Thomas Jefferson, who wrote in 1798 in the Kentucky Resolutions that “whensoever the General government assumes undelegated powers, it’s [sic] acts are unauthoritative, void, & of no force.” 2 He outlined no procedure for declaring a law “unauthoritative, void, & of no force,” but he established the concept that the state had the right to do so. Calhoun should not be acknowledged, either, as the man who took Jefferson’s ideas of nullification and applied them to his time, when the general government was arguably assuming undelegated powers. Calhoun followed many South Carolina 1 William Freehling, Prelude to Civil War; The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 156. 2 Thomas Jefferson, “Kentucky Resolutions” in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Volume 30: 1 January 1798 to 31 January 1799 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 543. 1 statesmen who embraced nullification publicly before he did. These firebrands were influenced by lowcountry planter Robert James Turnbull’s 1827 work The Crisis, which South Carolina governor James Hamilton, Jr., referred to as, “the first bugle-call to the South to rally.” 3 Turnbull, not Calhoun, set the nullification movement in motion. Nevertheless, the nullification movement owed much to Calhoun for his intellectual contribution. His innovation was to introduce a conception of nullification that clearly sought to preserve the union rather than to rend it apart. The radical diatribes expressed by the first backers of nullification in South Carolina were but shrill calls for resistance and had no political merit for the moderate South Carolinian who preferred compromise over confrontation. Through his writings, Calhoun introduced a notion of nullification more palatable to these moderates than any they had heard previously, one that did not make them fear disunion and civil war. He systemized the doctrine so it became a constitutional check rather than a battle cry; he grounded his theory in the existing framework of American law, thereby implying his hope for its perpetuity. Calhoun, unlike Turnbull before him, was wholly committed to union, and that sentiment made nullification acceptable to the many in the state that were also committed. They agreed with the novel interpretation of the Constitution that he alone had formulated. A comparison of Turnbull’s The Crisis to Calhoun’s draft of the 1828 “South Carolina Exposition” reveals the improvements that the latter made upon the former’s original doctrine. In turn, an analysis of Calhoun’s writings in comparison to the political thought of James Madison, the man widely regarded as the “Father of the Constitution,” reveals the originality and importance of the constitutional framework that Calhoun had devised. Though he had not devised the doctrine of nullification, his conception of the 3 Freehling, Prelude to Civil War, 128. 2 theory was a new creation. Within the nullification movement, Calhoun was the only one to inject his own ideas into the dispute. The Crisis received its title because it described what the author perceived as the current state of affairs in South Carolina. Much of the book is dedicated to an outline of the immediate crisis that the state faced—namely, a clash of interests with an apparently hostile northern majority. “The more National, and the less federal, the Government becomes,” Turnbull warned, “the more certainly will the interest of the great majority of the States be promoted, but with the same certainty, will the interests of the South be depressed and destroyed.” 4 Though the protective tariff boosted the success of the manufacturing states, it functioned as little more than “an indirect tax upon the people of the Southern States, amounting exactly to the difference between what they now pay, and the cheaper price at which they might obtain the article.”5 Even more pernicious than the tariff, however, were the efforts of the American Colonization Society to alter the southern institution of slavery. To Turnbull, the society’s early movements were enough to conjure visions of slave revolts, congressional interference, and ultimately, the ruin of the South. He firmly believed that the entire region, and South Carolina in particular, could not function without its peculiar institution. Slavery “is so intimately interwoven with our prosperity,” he claimed, “that to talk of its abolition, is to speak of striking us out of our civil and political existence. It is to remove from us the only labourers who can cultivate our soil. It is to cut oft’ all the resources of our wealth.”6 4 Robert James Turnbull, The Crisis (1827, repr., Danvers: General Books LLC, 2009), 13. Ibid., 125. 6 Ibid., 137. 5 3 At root, though, the “crisis” of which Turnbull wrote at length went beyond questions of economics, beyond the morality or even necessity of slavery. What truly threatened South Carolina, the underlying cause of all of the state’s immediate controversies, was a constitutional crisis. Members of the federal government, Turnbull maintained, were misinterpreting the Constitution by tending toward national consolidation. As such, he dedicated much of his writing to constitutional analysis in order to explain the issue. All of the problems, Turnbull declared, stemmed from a misinterpretation of Article I, Section 8, Paragraph 18 of the Constitution, which states that Congress has the right “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”7 The ambiguity of the phrase “necessary and proper” had already led to the McCulloch v. Maryland Supreme Court decision, which Turnbull believed faulty. In it, Chief Justice John Marshall decided that the phrase was meant to enlarge the powers of Congress, so that it was able to perform all the powers incidental to those specifically enumerated in the Constitution.8 Turnbull, however, buoyed by the records of the Constitutional Convention, stated that the clause had been inserted for the opposite purpose: “to narrow the discretion of Congress, as to the selection of its means in exercising its enumerated powers.”9 Congress had the ability to pass any law that was necessary and proper in regards to the execution of the specifically enumerated powers of the government, not to pass any law that it felt would improve the general welfare. Turnbull’s interpretation did not allow for 7 U.S. Constitution, art. 1, sec. 8. Turnbull, The Crisis, 36-40. 9 Ibid., 38. 8 4 the implementation of national banks, protective tariffs, or national abolition; the allegedly faulty interpretation of Congress allowed for pretty much anything. According to Turnbull, the Constitution granted to Congress very specific enumerated powers and reserved the rest for the states. Thus, Congress could not perform any powers not specifically delegated to them without usurping the powers of state governments; as a body, it was not free to pass any law for the sake of what it considered the general welfare, though Turnbull believed it was doing exactly that.10 “Before Congress can exercise any great substantive powers,” he stated, “it must place its finger upon that clause of the act of enumerated powers, which clearly confers the grant of power contended for.”11 Therefore, since the Constitution allowed Congress “To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises,” a tariff was legal for the purposes of revenue collection; it was not legal, however, for the protectionist purposes that it was being used for, as the Constitution did not grant Congress the power to protect industries.12 Those who pointed to the clause in the Constitution that gave Congress the power to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts” as evidence in favor of protectionism were erroneous as well in Turnbull’s eyes, as that power was specifically limited to “securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”13 Additionally, Turnbull argued that a clause in the section of the Constitution limiting state powers actually gave the power to promote industries to the states. Article I, Section 10, Paragraph 2 states, “No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, 10 Ibid., 40-46. Ibid., 27. 12 U.S. Constitution, art. 1, sec. 8. 13 Ibid.; Turnbull, The Crisis, 63-66. 11 5 lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it's [sic] inspection Laws: and the net Produce of all Duties and Imposts, laid by any State on Imports or Exports, shall be for the Use of the Treasury of the United States; and all such Laws shall be subject to the Revision and Controul of the Congress.”14 Though the states had to gain permission from Congress, they still possessed the right to impose duties; and since all revenue from such duties were explicitly placed in the federal treasury, the only purpose for such duties would be to encourage industries. Thus, not only was Congress using a power it did not have in imposing the tariff—it was usurping a right of the states.15 As Turnbull concluded, “1st.That money cannot be appropriated but for national purposes; and 2ndly, That no measure is national in its character, which refers to a subject over which the States, under the Constitution, can lawfully exercise their sovereignty.”16 The solution to this constitutional crisis, Turnbull argued, could not be found within the federal judiciary, the solution proposed by many moderates. The courts, as part of the national government, were too attached to the interest of expanding federal powers to be impartial arbiters.17 Furthermore, the tariff laws were, “in their form,” absolutely constitutional; a court could not factor motive and interest into its decisions, and as Congress was in fact given the power to impose duties, any case brought against it in federal court would certainly be dismissed.18 The alleged fact that Congress passed the tariff for the unconstitutional purpose of encouraging manufactures would be deemed irrelevant. 14 U.S. Constitution, art. 1, sec. 10. Turnbull, The Crisis, 66-69. 16 Ibid., 94. 17 Ibid., 101, 116-117. 18 Ibid., 177. 15 6 The representatives of the states in Congress were not to be relied upon either, though some of them could be expected to sympathize a bit more with the plight of the state. “There is a responsibility, it is true, of our own members of Congress to the people of South Carolina. But these men can do no more than their duty,” Turnbull argued. “When once the people of the Northern and Western States, who constitute the majority, shall decide, that we shall pay tribute to them, what becomes of that safeguard called ‘political responsibility?’”19 Neither the courts nor Congress would save South Carolina. Turnbull’s answer to the crisis was simple, if inelegant: “To our State Legislature alone we must look.”20 Without laying out any particular protocol or system, he insisted throughout The Crisis that the South Carolina legislature “shall raise its voice against any usurped act of the Government” and had “the undoubted right, to call the General Government to account for an abuse of its delegated powers.”21 Simple resistance was Turnbull’s answer—and though he never referred to it as such, this answer was a primitive form of nullification. The state legislature was to refuse obedience to any law that usurped its own rights. Calhoun, in his draft of the South Carolina “Exposition,” performed a similar constitutional analysis. He agreed that Congress’s only power to encourage manufactures was its ability to grant patents.22 He agreed that the judiciary could not be the sole interpreter of the Constitution, as it could not possibly remain neutral and could not adjudicate based on the motivation of a law.23 Even their language was somewhat 19 Ibid., 102. Ibid. 21 Ibid., 103, 121. 22 John C. Calhoun, “South Carolina Exposition” in The Papers of John C. Calhoun, November 25, 1828, Volume X: 1825-1829 (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1977), 446. 23 Ibid., 446, 500, 502, 506. 20 7 similar: where Turnbull stated that “the best rule of interpretation is the plain letter of the Constitution,” Calhoun asserted that the “only safe rule is the Constitution itself.” 24 On the fundamentals of the document, the two seem in complete accord. Calhoun writes at length about the nature of congressional powers, and echoes Turnbull’s interpretation: “The powers of the General Government are particularly ennumerated and specifickly delegated; and all powers, not expressly delegated, or which are not necessary and proper to execute those that are granted, are expressly reserved to the States and the people.”25 Calhoun, like Turnbull, believed in the ultimate sovereignty of the states as the bodies that had originally created the Constitution. Since they were the ones to initially consent to the document, it was up to them, and them alone, “to decide in the last resort whether the compact made by them be violated.”26 When a state felt that its powers were being usurped, it had a “Constitutional right… to interpose in order to protect” those powers. Of states that post-dated the Constitution, he said nothing; he likely believed that since these states consented to the document’s rule when joining the union, they, too, had the power to interpose. Like Turnbull, Calhoun advocated a solution based on nullification.27 Despite such agreement, however, the remedies prescribed by Turnbull and Calhoun bore significant differences—differences crystallized by “a striking distinction between government and sovereignty” that Calhoun acknowledged and Turnbull denied.28 Calhoun disagreed with Turnbull’s assertion that the state legislatures were sufficient to fulfill the role of original sovereignty. A state’s government, he argued, 24 Ibid., 446; Turnbull, The Crisis, 53. Calhoun, “South Carolina Exposition,” 496. 26 Ibid., 508. 27 Ibid., 512. 28 Ibid., 496. 25 8 passed and carried out the laws within its domain, but that did not make it sovereign. The people of any respective state were the sovereigns. It was they who had ratified the Constitution, not the legislature. Thus, only a state convention, democratically elected for the specific occasion, could accurately represent that sovereign power. A convention, once convened, would be able to determine whether or not a particular law was unconstitutional and therefore null and void.29 This differed markedly from Turnbull, who, in The Crisis, argued specifically against the need for a state convention to act as the sovereign. Aware of the legal principles that Calhoun relied upon to declare the people of a state the supreme authority—that the Constitution had been ratified by conventions, not legislatures— Turnbull nevertheless characteristically stuck to a strict, unimaginative interpretation of constitutionalism.30 “Under the State constitution,” he asserted, “all power, which is not reserved to the people in a bill of rights… is invested in the State Legislature.” 31 Since the people had no right to a nullifying convention explicit in the Constitution, that power was reserved to the legislature, regardless of original sovereignty. William Freehling embraced Calhoun’s conception of nullification as advantageous to the nullification movement because, unlike Turnbull’s, his defined an ultimate and final authority on the Constitution: the people of the state. Turnbull, who maintained that the state government was able to check usurpation by the latter, never established one branch of government as sovereign over the other. Thus, no “final” interpretation of the Constitution could exist in a dispute; a nullifying state government would simply resist its national government, thus making the use of force almost 29 Ibid., 510, 512. Ibid., 110-112, 121. 31 Ibid., 121. 30 9 inevitable. Furthermore, Calhoun’s theory of nullification did not blur the line between lawmaking and constitution-making, as Turnbull’s did. The very heart of the constitutional crisis that the two acknowledged was that Congress, in its willful ignorance of the checks upon its power, was to their mind interpreting the nation’s Constitution as it went along. Though Congress had no constitutional power to create a bank, internal improvements, or a protective tariff, it went ahead and did so anyway. Under Turnbull’s plan, state governments could just as easily take hold of Constitution for their own purposes, and shut down even legitimate exercises of federal power that did not suit the state simply by refusing to follow a law. It could do that despite the fact that the state legislature was not a party to the creation of the Constitution, and therefore had no legitimate right to make any sort of alteration to it. The legislature’s role was limited to mundane legislative powers. Calhoun’s plan, on the other hand, separated constitutional authority from governmental power, and thus prevented those in office from exerting undue influence on the highest law of the land.32 No government, be it Congress or a state legislature, would have the unlimited ability to interpret the Constitution to its own benefit. As much as Calhoun’s conception improved upon Turnbull’s in a legal and theoretical sense, it is difficult to assess that improvement’s tangible contribution to the nullification movement. Freehling argues that Calhoun’s breakthrough gave other defenders of nullification “the immense intellectual security of being able to answer their critics with arguments based squarely on cherished American principles.”33 This argument certainly has merit. James Hammond, a prolific contributor of nullification 32 33 Freehling, Prelude to Civil War, 159-165. Ibid., 166. 10 editorials in South Carolina, praised an essay of Calhoun’s for making “everything as clear as a sun beam” and was probably buoyed by the soundness of reason that Calhoun contributed to nullification.34 However, on a grander scale, it is unlikely that Calhoun’s force of logic held much influence over the people of South Carolina who would in 1832 sweep nullifiers into a majority of the state government. Throughout the nullification campaign, people were swayed by appeals to emotion, not reason. George McDuffie, one of the nullifiers’ most successful orators, gained traction with the masses with his forty-bale theory—that claimed that southern cotton producers lost forty bales to the tariff for every hundred produced. The theory, though based on an absurdly inaccurate understanding of economics, nevertheless managed to stir up enough outrage among the masses that it was in time accepted as fact among most South Carolinians. In fact, the theory succeeded so wildly precisely because it so studiously avoided anything resembling nuance. According to McDuffie, raw cotton was shipped to England in exchange for manufactured cloth—always. Since the tariff greatly increased the price of this cloth, it in effect greatly decreased the value of the raw cotton.35 Of course, the merchants who acquired capital from the cotton market did not spend it exclusively on manufactured cloth, and thus avoided McDuffie’s dreaded 40 percent markdown.36 Thus, the forty-bale theory simplified economics to the point of inaccuracy; however, since it also made intuitive sense to most free-trade South Carolinians, it shifted the debate greatly in favor of the nullifiers.37 34 Ibid. Ibid., 194. 36 Ibid., 195. 37 Ibid. 35 11 Thus, though Calhoun’s work was actually intellectually coherent, its greatest political value was in its sentiment. The fact that he had bothered to treat his doctrine as a part of a constitutional whole was a sign of commitment to the union that firebrands such as Turnbull and McDuffie had not exhibited. In The Crisis, Turnbull admitted up front that his “feelings… are more sectional than they are national.”38 Though he certainly held some affinity for the national union, he took a largely devil-may-care approach to the prospect of future disunion. “We are amply furnished with the means of protecting ourselves, and of perpetuating our policy under any emergency, and without needing any assistance from them,” he boldly proclaimed.39 “Disunion did I say? Whether disunion shall approach us, rests not with ourselves, but with our Northern brethren.” 40 From his vantage point, South Carolina needed to resist federal usurpation more than it needed to preserve its place in the union. Calhoun, on the other hand, was equally concerned with defending the interests of South Carolina and preserving the Union and the integrity of the Constitution. His nullification was not merely a convenient resistance, but a constitutional check—even a safeguard against disunion. Unlike Turnbull, he appeared willing to accept an override of nullification as long as that override was constitutional. For that, he pointed to the Article 5 of the Constitution, which stated that “when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States,” a proposed amendment would be added onto the document.41 Thus, if three-fourths of the states objected to a state’s use of nullification, 38 Turnbull, The Crisis, 11. Ibid., 23. 40 Ibid., 128. 41 U.S. Constitution, art. 5. 39 12 they could amend the Constitution to explicitly reserve for Congress the right to pass the law that was being nullified.42 Calhoun, then, saw his doctrine not solely as a means to protect South Carolina’s interests, but as a way to preserve the union. He penned the “South Carolina Protest” as a man “anxiously desiring to live in peace with their fellow citizens, and to do all that in them lies to preserve and perpetuate the union of the States and the liberties of which it is the surest pledge—but feeling it to be their bounden duty to expose and to resist all encroachments upon the true spirit of the Constitution.”43 An instance of nullification illreceived by the vast majority of states, he believed, need not result in civil war. Instead, that majority could, in accordance with the guidelines of the Constitution, peacefully strike down the act of nullification; and if no such majority existed, so much the better, for the rights of the minority would be preserved through legal means. Either way, each side was granted a legitimate power to defend its own interests without turning to the sword. Before this point, nullification in South Carolina had been more of a fringe movement, led by radicals such as Turnbull. The South Carolina moderate, a man resentful of federal encroachments but apprehensive about the prospect of disunion, did not see their nullification as an acceptable solution to his state’s problems. He held out hope that the Jackson administration would be more kind to the South than the Adams administration had been, and that the tariff would be reduced soon after the payment of the national debt.44 South Carolina politicians responded to this popular sentiment by tempering their rhetoric; even George McDuffie, the most passionate of nullifiers, 42 Calhoun, “South Carolina Exposition,” 520. John C. Calhoun, “South Carolina Protest” in The Papers of John C. Calhoun, 539. 44 Freehling, Prelude to Civil War, 142. 43 13 concealed his militancy for some time, afraid that he would offend constituents and derail Jackson’s candidacy.45 The nullifiers’ faith in Jackson ultimately turned out to be displaced, however. By 1832, he had not delivered on tariff reform, and his infamous Nullification Proclamation—which denounced the doctrine as “incompatible with the existence of the Union”—led many to believe that he would not advocate for South Carolina’s rights. The South Carolina moderate who had earlier placed his faith in Jackson was welcomed to the cause of nullification through Calhoun’s doctrine, which artfully asserted that nullification was, in fact, compatible with the Union. In 1832, the support of moderates would pay dividends at the polls, and Calhoun’s intellectual contribution would prove invaluable to movement. The appeal of his work was that it went beyond the particular moment in South Carolina politics. It was not just about the tariff or slavery, but about the general workings of the United States government. The people of South Carolina who supported it, did so with the hope that it would become the ruling logic of the land. Outside of the state, however, it gained little traction. When South Carolina finally did take the plunge and nullified the tariff in 1832, its actions were widely denounced by other southern legislatures. The Alabama legislature pronounced the “alarming scheme “unsound in theory and dangerous in practice”; the Georgia lawmakers believed that the “mischievous policy” was “rash and revolutionary”; the Mississippi representatives denounced South Carolina for acting with “reckless precipitancy.”46 Despite the harsh language, most southern states remained sympathetic to South Carolina, for they, too, felt the same anxieties over the tariff and slavery. However, they 45 46 Ibid., 143-144. Ibid., 265; State Papers on Nullification (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, 1834), 219-223, 230, 274. 14 opposed nullification for a variety of reasons: Georgia and the southwestern states depended on Jackson to help them seize Indian lands (Jackson, ironically, had nullified a Supreme Court decision declaring states had no right to do so); North Carolina and Tennessee also followed the president’s lead; Kentucky remained aligned with Clay and his nationalist policies; and Virginia simply opposed South Carolina’s methods on constitutional grounds. Though Calhoun’s meticulously thought out nullification to be consistent with both the spirit and letter of the Constitution, the only state to see it as such was South Carolina. The doctrine drew the ire of many who held a fundamentally different vision of America. In Virginia and in much of the South, that vision was forged primarily by James Madison, the man at the center of any constitutional discussion. Ironically, though many of Madison’s doctrines diametrically opposed Calhoun’s, a few of his writings actually influenced the South Carolina statesman’s work on nullification. In the “Exposition,” Calhoun drew support from Madison’s Report of 1800, which defended the rights of states against federal overreach.47 In the report, Madison asserted, “that in cases of a deliberate, palpable and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the State[s], who are parties thereto have the right and are in duty bound to interpose to arrest the act and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities[,] rights and liberties appertaining to them.”48 The interposition of which Madison spoke in 1800 sounded to Calhoun and his fellow nullifiers exactly like the nullification they were advocating for thirty years later. In 1830, prominent nullifier and U.S. Senator Robert Hayne sent Madison copies of his 47 Calhoun, “South Carolina Exposition,” 508. James Madison, “Report on the Virginia Resolutions” in Jonathan Eliot, ed., The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787, Volume 4, (New York: Burt Franklin, 1888), 547. 48 15 speeches, hoping that the doctrine would win an endorsement from the American with the strongest constitutional credentials.49 Much to his chagrin, however, the response he received was not a vote of encouragement, but a lengthy rebuttal that denounced nullification as “pregnant with consequences subversive of the Constitution.” 50 Madison made clear that the interpositions that he had advocated for in 1800 were meant to be undertaken cooperatively by several states acting through specific constitutional procedure, not by a lone state that insisted on utilizing its original sovereignty.51 Though Madison did support the right of the states to seek redress from federal usurpations, nullifiers were incorrect in assuming that he would leap to embrace nullification. In truth, though he favored a balanced government in which states checked federal action, his ideal form of government was decidedly nationalistic. The failure of the Articles of Confederation had convinced him prior to his writing of the Constitution that “every concession in favor of stable Government not infringing fundamental principles” should be made.52 The Constitution that he envisioned would create a “due supremacy of the national authority” while leaving the states in a “subordinately useful position.”53 Madison, though supportive of local governments, feared the power of runaway state majorities to oppress the rights of the minority. While serving in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1784 to 1786, he saw such majorities essentially hijack state level 49 Ford, Lacy K. “Inventing the Concurrent Majority: Madison, Calhoun, and the Problem of Majoritarianism in American Thought.” The Journal of Southern History 60 (1994), 53. 50 James Madison to Robert Y. Hayne, April 3 or 4, in Hunt, ed., Writings of James Madison, IX, 388. 51 Ibid. 52 Ford, “Inventing the Concurrent Majority,” 24-25; James Madison to Edmund Randolph, April 8, 1787, in Papers of James Madison, Volume IX, ed. by Hutchinson (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1962), 318. 53 James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787, in Papers of James Madison, Volume IX, 369. 16 government in pursuit of the interests of those that comprised them.54 This often led to legislation that Madison considered dangerous. He thus believed that these state-level majorities, unless checked, posed the greatest threat to the well-being and stability of the nation—for “the majority who alone have the right of decision, have frequently an interest real or supposed in abusing it.”55 On the other hand, he saw no parallel issue extended over the entirety of the United States. He believed that in a large republic, “you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who fell it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other.”56 The numerous factions throughout the vast extent of the nation’s territory—far more numerous than those found within a single state—would work against each other, and were thus more likely to frustrate each other’s selfish ambitions that to impose their own on a helpless minority.57 As the primary writer of the Constitution, Madison’s beliefs tended to inform his contribution to what would become the highest law of the land, which in turn informed the national consciousness regarding the nature of American government. Calhoun, however, no longer bought into this conception by the time he adopted nullification. In the “Exposition,” he wrote, “That our industry is controlled by many, instead of one… forms not the slightest mitigation of the evil. In fact instead of mitigating it aggravates. In our case one branch of industry cannot prevail, without associating others; and thus 54 55 Ford, “Inventing the Concurrent Majority,” 25-26. James Madison to George Washington, April 16, 1787, in Papers of James Madison, Volume IX, 384. 56 57 Jacob E. Cook, ed., The Federalist (Middletown: Wesleyan), 63-65. Ibid., 56-65; Ford, “Inventing the Concurrent Majority,” 27-31. 17 instead of a single act of oppression we bear many.” 58 To him as well as other South Carolinians, it had become clear that the nation’s varied interests were not checking each other, but were joining forces. What Madison believed impossible—the formation of a permanent national majority—seemed, to Calhoun, a reality.59 Calhoun, as Madison did, used his experience to formulate a solution to a constitutional crisis. Madison sought to divide sovereignty between state and federal governments, ultimately relying on the will of the national majority; Calhoun placed sovereignty into the hands of the states and their respective inhabitants, and left federal policy up to a different kind of majority: what he called the “concurring majority.” This majority, in Calhoun’s words, “is estimated, not in reference to the whole, but to each class or community of which it is composed” with “the assent of each taken separately, and the concurrence of all constituting the majority.”60 The United States was not made up of a single national people, Calhoun maintained, but of several communities, the states. For any national law to achieve legitimacy, he argued, it must have the consent of a large majority of those communities. 61 He reasoned that no law could be valid, even with the support of an absolute majority, if it undermined entire communities vital to the survival of the nation. Thus, under a system ruled by the concurrent majority, a national law must not stand that did not have the consent of several states, regardless of how the absolute national majority voted on it. The state, he insisted, could call a convention of the people that could nullify that law. A convention would then be called among the several states of the nation, who would determine whether to uphold the nullification or 58 Calhoun, “South Carolina Exposition,” 490. Ford, “Inventing the Concurrent Majority,” 33-34, 44. 60 John C. Calhoun, Calhoun to Hamilton in The Papers of John C. Calhoun, XI, 640. 61 Ibid., 613-649; Ford, “Inventing the Concurrent Majority”, 47. 59 18 to prevent it by was of constitutional amendment. Though the concept was new, it was not incompatible with the existing foundation of the American constitution—in fact, Calhoun drew directly from the amending power of the constitution. He did not suggest anything radical, simply that an additional safeguard be permitted in order to protect the rights of certain classes. John C. Calhoun most certainly deserves his reputation as an ardent supporter of state autonomy. He did not consider the American people as a truly national people, but as an association of different communities. These communities were ontologically prior to the nation as a whole, and thus state identity was bound to triumph over any attempt at national coherence. However unconvinced Calhoun remained of the strength of the bonds between the several states, though, he most certainly valued those bonds. Though his reformulation of American constitutionalism emphasized the single state over the whole nation, his purpose was to preserve the nation. He embraced nullification as more than the solution to South Carolina’s problems, but as the solution to the American constitutional problem that seemed sure to destroy the union. The works Calhoun created in favor of nullification and the concurrent majority were, to some extent, built upon the backs of others. He refashioned Turnbull’s nullification in order to create a permanent constitutional check rather than a momentary protest. He reformulated Madison’s constitutionalism in order to make the nation safe for a future with permanent political coalitions. In his derivations, however, he created something entirely new: a constitutional framework which the majority of South Carolina came to believe would not only protect their rights, but would perpetually preserve their place within the union. Though this framework failed to take root on a national level, its 19 acceptance within South Carolina played a big part in transforming the nullification movement from a fringe revolt into a political force. 20