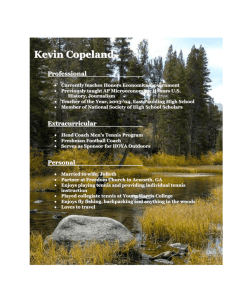

Community Development and Sport Participation

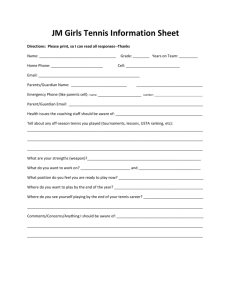

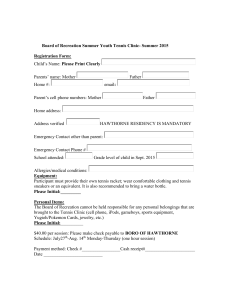

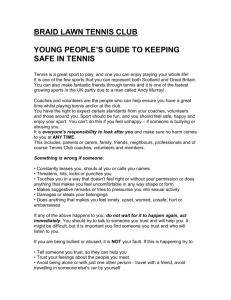

advertisement