Meeting the Madwomen: Mental Illness in Women in Rhys's Wide

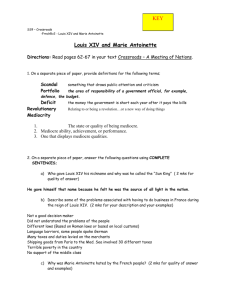

advertisement