Sperm wars illuminated : Nature News

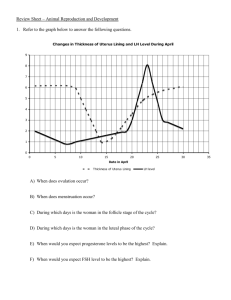

Page 1 of 3

Published online 18 March 2010 | Nature | doi:10.1038/news.2010.135

News

Sperm wars illuminated

Insect sperm fight one another with brute force and chemical weapons.

John Whitfield

When the sperm of different male insects meet inside a female, they use

everything from wrestling to chemical warfare to try and fertilize as large

a share of her eggs as possible, according to two studies published this

week. The studies also show that females don't just let the battle take its

course, but manipulate it to their own ends.

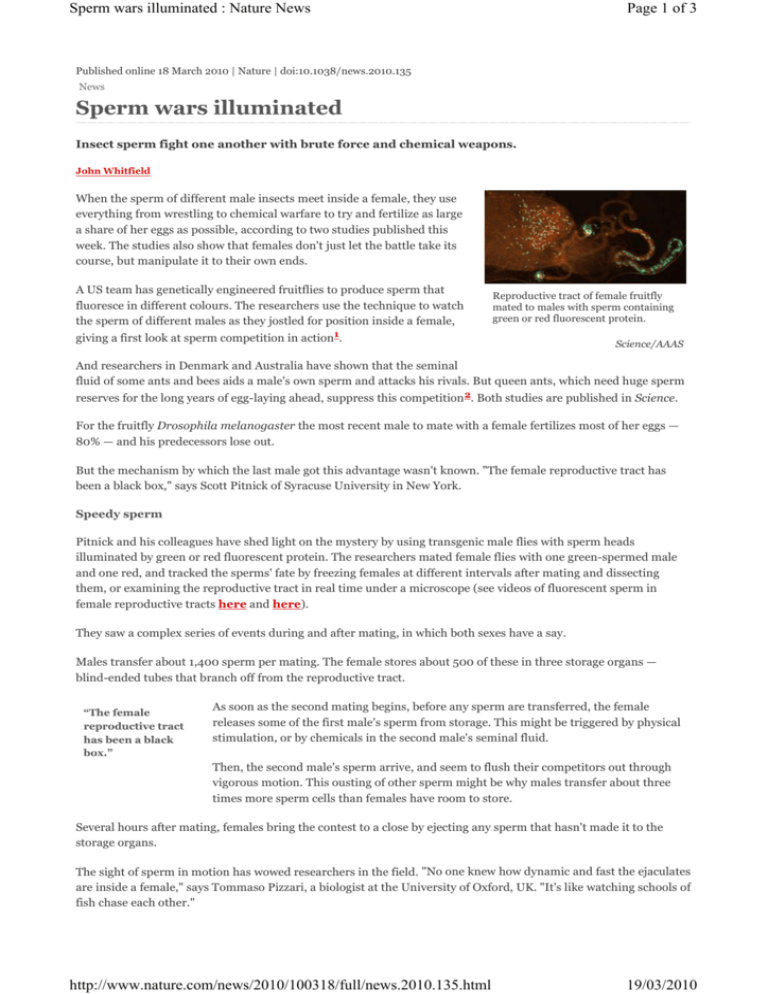

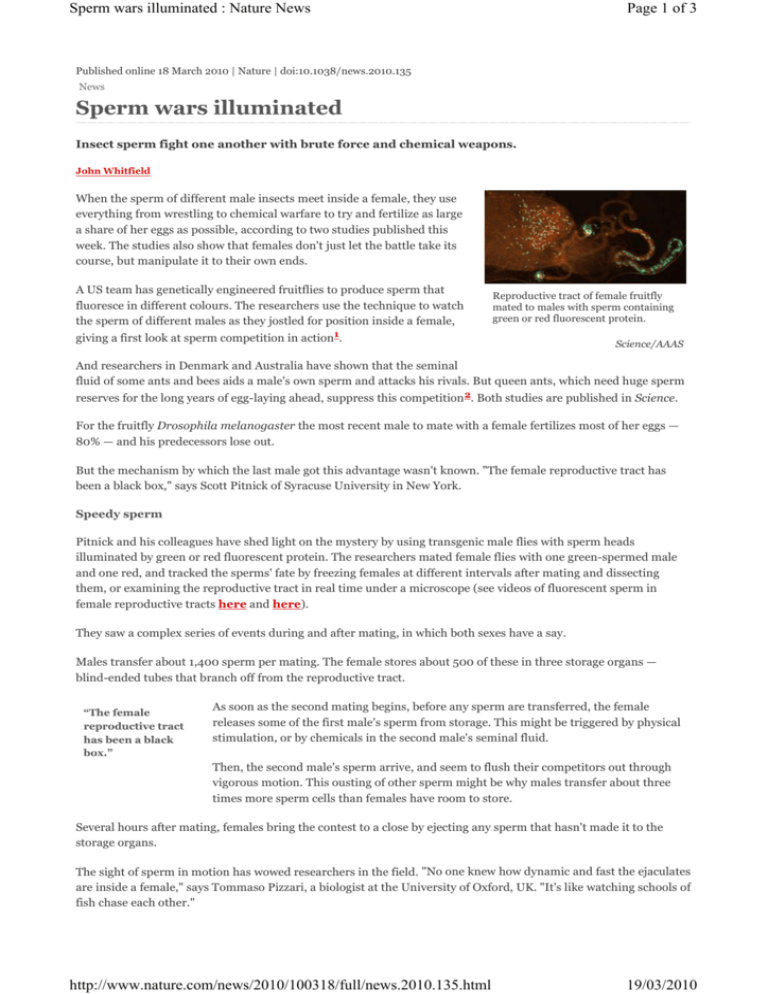

A US team has genetically engineered fruitflies to produce sperm that

fluoresce in different colours. The researchers use the technique to watch

the sperm of different males as they jostled for position inside a female,

Reproductive tract of female fruitfly

mated to males with sperm containing

green or red fluorescent protein.

giving a first look at sperm competition in action1.

Science/AAAS

And researchers in Denmark and Australia have shown that the seminal

fluid of some ants and bees aids a male's own sperm and attacks his rivals. But queen ants, which need huge sperm

reserves for the long years of egg-laying ahead, suppress this competition 2. Both studies are published in Science.

For the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster the most recent male to mate with a female fertilizes most of her eggs —

80% — and his predecessors lose out.

But the mechanism by which the last male got this advantage wasn't known. "The female reproductive tract has

been a black box," says Scott Pitnick of Syracuse University in New York.

Speedy sperm

Pitnick and his colleagues have shed light on the mystery by using transgenic male flies with sperm heads

illuminated by green or red fluorescent protein. The researchers mated female flies with one green-spermed male

and one red, and tracked the sperms' fate by freezing females at different intervals after mating and dissecting

them, or examining the reproductive tract in real time under a microscope (see videos of fluorescent sperm in

female reproductive tracts here and here).

They saw a complex series of events during and after mating, in which both sexes have a say.

Males transfer about 1,400 sperm per mating. The female stores about 500 of these in three storage organs —

blind-ended tubes that branch off from the reproductive tract.

“The female

reproductive tract

has been a black

box.”

As soon as the second mating begins, before any sperm are transferred, the female

releases some of the first male's sperm from storage. This might be triggered by physical

stimulation, or by chemicals in the second male's seminal fluid.

Then, the second male's sperm arrive, and seem to flush their competitors out through

vigorous motion. This ousting of other sperm might be why males transfer about three

times more sperm cells than females have room to store.

Several hours after mating, females bring the contest to a close by ejecting any sperm that hasn't made it to the

storage organs.

The sight of sperm in motion has wowed researchers in the field. "No one knew how dynamic and fast the ejaculates

are inside a female," says Tommaso Pizzari, a biologist at the University of Oxford, UK. "It's like watching schools of

fish chase each other."

http://www.nature.com/news/2010/100318/full/news.2010.135.html

19/03/2010

Sperm wars illuminated : Nature News

Page 2 of 3

Long struggle

Among female insects, the champions of storing and manipulating sperm are queen ants and bees.

In the largest and most complex insect societies, such as honeybees, and leafcutter and army ants, queens mate

with up to 20 males in a few hours. Males die after mating, but their sperm can live on for years.

A leafcutter ant queen, for example, takes around 100 million–400 million sperm on board. Over the next decade

or two, she will use them to fertilize some 50 million–150 million eggs. Honeybee queens have shorter lives, but

might still produce more than a million offspring.

Sperm don't simply wait their turn inside. "The queen's body is an

arena where sperm are allowed to fight it out for a while," says

Jacobus Boomsma, a population biologist at the University of

Copenhagen.

ADVERTISEMENT

To see what weapons males used in this fight, Boomsma and his

colleagues put sperm from male bees and ants on a microscope slide

with either saline, a male's own seminal fluid, or that of another male.

Sperm survived longer in their own male's seminal fluid, but died

more quickly in another male's. The fluid seems to contain chemicals

that nurture a male's own sperm and attack the sperm of other males.

Studies of honeybees suggest that it is proteins that attack alien cells,

in the same way the immune system does inside the body.

Uneasy truce

For species in which queens mate just once, such as bumblebees, sperm of different males never meet, so there is

no competition. The seminal fluid of these species does not harm rival sperm, the researchers found.

"Self-recognition is more pronounced in species with higher levels of sperm

competition. It's exactly what you'd expect," says Pizzari.

By letting sperm fight it out, females let the fittest males father their offspring. But

were this competition to continue, it might threaten the long-term supplies of sperm

— particularly in leafcutter ants, where queens pay out just a few sperm to fertilize

each egg. "Every sperm they store is precious," says Boomsma.

To see how these queens police sperm competition, Boomsma's team added fluid

from the leafcutter queen's sperm storage organ to the mix. This, they say, cancelled

out the negative effect of another male's seminal fluid.

It is thought that queens benefit from multiple matings by producing more

genetically diverse offspring, and so healthier colonies. If this is so, it might also be

in a male's interest not to do too much damage to his rival's sperm, notes Tracey

Chapman, an evolutionary biologist at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, UK

"Once they're in the storage organs, everybody had better settle down," she says.

Bumblebee queens mate

just once so the sperm of

these species d not

compete.

References

1. Manier, M. K. et al. Science advance online publication doi:10.1126/science.1187096

(2010).

2. den Boer, S. P. A. , Baer, B. & Boomsma, J. J. Science 327, 1506-1509 (2010).

B. Baer

Comments

http://www.nature.com/news/2010/100318/full/news.2010.135.html

19/03/2010

Sperm wars illuminated : Nature News

Page 3 of 3

If you find something abusive or inappropriate or which does not otherwise comply with our Terms or Community

Guidelines, please select the relevant 'Report this comment' link.

Comments on this thread are vetted after posting.

There are currently no comments.

Add your own comment

This is a public forum. Please keep to our Community Guidelines. You can be controversial, but please don't get personal or

offensive and do keep it brief. Remember our threads are for feedback and discussion - not for publishing papers, press releases

or advertisements.

You need to be registered with Nature to leave a comment. Please log in or register as a new user. You will be re-directed back to

this page.

Log in / register

About NPG

Contact NPG

RSS web feeds

Help

About Nature News

Nature News Sitemap

Privacy policy

Legal notice

Accessibility statement

Terms

Nature News

Naturejobs

Nature Asia

Nature Education

© 2010 Nature Publishing Group, a division of Macmillan

Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved.

Search:

partner of AGORA, HINARI, OARE, INASP, CrossRef and

COUNTER

http://www.nature.com/news/2010/100318/full/news.2010.135.html

19/03/2010