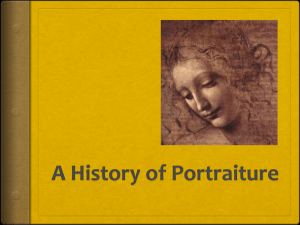

Portraits of patients and sufferers in Britain, c. 1660

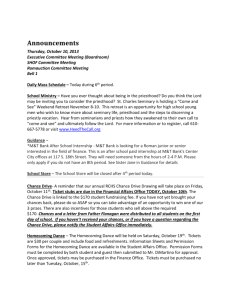

advertisement