Credit Guarantee Schemes for SME lending in Central, Eastern and

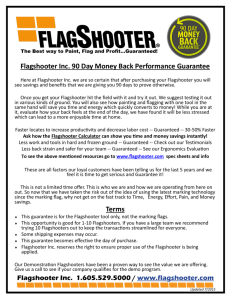

advertisement