Misrepresentation & Mistake Introduction Terms or Representations

advertisement

Law 231 L 06

Misrepresentation & Mistake

Introduction

Contractual obligations are based on notions of agreement and consent. Under certain

circumstances the apparent agreement or consent may be vitiated thus rendering the

contract either void or voidable. This is due to the fact that the "agreement" is flawed

in some fundamental manner, such that either it cannot be said that both parties agreed

/ consented to the same thing, or that the agreed subject matter does not in fact exist.

IN certain situations the same facts may involving misrepresentation and / or

mistake (Leaf v International Galleries [1950] 2 KB 86). The decision as to which

doctrine upon which to base one's argument has to be made with an eye to the

availability and desirability of the various remedies.

Where a contract is declared void, it is set aside and treated as if it never existed "void ab initio", and no rights or duties are created. In contracts for the sale of goods

this means that no title passes and 3rd party purchasers are left in a vulnerable

position. Some agreements affected by mistake provide examples of void contracts.

Voidable contracts on the other hand give rise to rescission, but until one party elects

to exercise that right, the contract remains valid. The right to rescind is also subject to

a number of obstacles that can result in the right being lost. Agreements affected by

misrepresentation provide examples of voidable contracts.

Terms or Representations

Statements (which are false) made in the course of pre-contractual negotiations may

be classified as "mere puffs", misrepresentations or contractual terms. "Mere puffs"

generally do not involve legal consequences. Statements that induce a party to

contract are classified as misrepresentations. In the latter case there will be no remedy

for breach of contract but rescission or damages, or both may be available. Certain

statements may be incorporated as terms of the contract. Some may be regarded as

collateral warranties, breach of which give rise to a right to damages.

-1-

Law 231 L 06

Oscar Chess v Williams [1957] 1 All ER 325 (CA)

Defendant said that it was a 1948 model, but in fact, it was a 1939 model, and was

hence worthless. Defendant honestly believed that it was a 1948 model, and so was

not fraudulent. Term or misrepresentation? Trial judge found in favour of the

plaintiff, and the Court of Appeal upheld the appeal - not a warranty / guarantee,

merely a pre-contractual misrepresentation. Denning LJ said that one has to look at

what the parties intended.

Dick Bentley v Harold Smith Motors [1965] 2 All ER 65 (CA)

Car sale to plaintiff. Defendant stated 20,000 miles on the clock since the new engine

had been fitted. Actually, the car had done much more than this, i.e. - there was a

false statement. Plaintiff seeked damages for breach of warranty. Trial judge found

in favour of the plaintiff, and the Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal.

The difference between this case and the one above is that in the latter case the

defendant was a business, where as in Oscar Chess v Williams the buyer was a

business buying for a private individual.

Misrepresentation Act 1967, s.1

Historically, there was no claim to damages or for misrepresentation, unless it was

fraudulent. It was then classes as honest. This was changed by the Misrepresentation

Act 1967. Non-fraudulent misrepresentations now classified either as negligent or

completely honest.

Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] 2 All ER 5 (CA)

This case doesn't come under the Act, as the facts pre-date 1967.

The case involves a forecast by Esso's experts of the throughput of fuel in a garage

that Mardon proposed to get the franchise of. The forecast was for 20,000 gallons.

Originally:

New Entrance:

-2-

Law 231 L 06

Esso knew about these new plans, so was their statement a term or not? Court of

Appeal said that it was a collateral warranty and a negligent misrepresentation.

Denning LJ said that it was not a guarantee, but is a warranty on reasonable

expectation, and that as Esso had specialist knowledge and skill there was a warranty

that the forecast was sound and reliable. Hence, although Denning LJ could not apply

the Act to the case, he applied the spirit of the Act to the case.

Fraud is much more difficult to prove, misrepresentation less so (on the basis of

probability). Negligent misrepresentation is a statement of fact, whereas if it is

opinion, there can still be claims for negligence without entering contract law.

Misrepresentation

It must be a false statement of fact (not opinion or intention) which induces the

representee to enter the contract. Silence does not (in general) constitute a

misrepresentation, unless a change in circumstances demands further disclosure.

Knowledge (of the representee) of its falsity bars relief.

Bisset v Wilkinson [1957] AC 177

Sale of a farm. Capacity - 2,000 sheep - seriously incorrect. Held as an expression of

belief, not fact, as the landlord was an absentee landlord.

→ silence doesn't generally⇒ a misrepresentation

Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885) 29 Ch D 459

This case deals with intention

Prospectus inviting loans from the public, the capital was to be used for the

improvement of buildings. In fact, it was used to pay off debts. The court ruled that

this was a statement of fact.

Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon [1976] 2 All ER 5 (CA)

Smith v Chadwick (1884) 9 App Cas 187

Redgrave v Hurd [1881) 20 Ch D 1

With v O'Flanagan[1936] Ch 375

-3-

Law 231 L 06

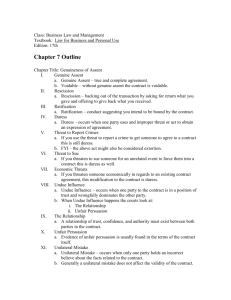

Classification of Misrepresentation

There are three types of misrepresentation - fraudulent; negligent; innocent.

Statements with do not induce a party to contract but which are acted in reliance upon

by the representee are best classified as mis-statements and are dealt with under the

law of tort.

i)

Fraudulent (knowingly or recklessly made) - Tort of Deceit

Derry v Peek (1889) 14 App Cas 337 (HL)

Prospectus for share investment. The company claimed that they had Board of Trade

consent for steam or mechanical power for their trams instead of horses. This was not

true - although they had applied to the Board of Trade, the company was refused

permission. There followed a claim of fraudulent misrepresentation, and the company

claimed that the false statement had not been made knowingly.

House of Lords - test for deceit (Lord Hirschell):

1) knowingly

2) without belief in its truth

3) recklessly (careless as to whether true or false)

Thomas Witter Ltd v TBP Industries Ltd [1996] 2 All ER 573

Carpets - audited and management accounts. One-off expense - not normally there, so

more profitable. Failed to disclose the difference bases on which the accounts were

prepared. The one-off expense was in fact only £50,000, not £120,000 as had been

claimed. Was this a fraudulent misrepresentation? The court said that there had been

no fraud, but that there had been recklessness that required some element of

dishonesty - the company had only been negligent.

This seems to say that the line is drawn - honest belief, when you ought to have

checked something out, is deemed to be negligence.

ii)

Negligent (carelessly made)

Misrepresentation Act 1967, s.2(1)

Hedley Byrne - burden of proof on the plaintiff

s.2(1) - burden of proof on the defendant

-4-

Law 231 L 06

Given the above, most plaintiffs will probably try to bring their case under s.2(1)

Howard Marine & Dredging Co Ltd v A. Ogden & Sons [1978] 2 All ER 1134 (CA)

The defendant (Ogden) chartered some barges from the plaintiff to dump some waste

at sea. They were informed that the barges could take up to 1,600 tons in weight,

based on the manager's reference to the Lloyds register of ships. But, the barges were

in fact only capable of taking 1,100 tons, and this information was in the manager's

possession. Therefore, the contract could not be completed in time, so they stopped

paying the charter fees. Sued, arguing negligent misrepresentation under s.2(1) and

common law. The Court of Appeal said that the manager had been honest. Denning

LJ (in the minority) said that the manager's belief was a perfectly "honest" belief.

However, the rest said that it was not reasonable for the manager to not have checked

his own company's documents, and he was therefore liable unders.2(1).

Also, note in this case, that there is no liability under Hedley Byrne.

iii)

Innocent {neither knowingly, recklessly or carelessly made)

Remedies for Misrepresentation

How a false statement is classified is of major significance in determining the

remedies available to the representee who is induced by it to enter a contract and

suffers loss as a consequence.

i)

Rescission

The term "rescission" appears to have more than one usage in legal disclosure but is

used here to signify that a contract is to be set aside due to some flaw in its formation.

This should be distinguished from another common usage, namely that a party may

"rescind" for breach of contract and claims damages, where it would be more accurate

to state that the innocent party repudiates the contract and is discharged from further

performance. Rescission then involves the setting aside of a contract and returning

the parties to their pre-contractual position. The remedy is available for all types of

misrepresentation, however it is an equitable remedy and is not available as of right,

only at the discretion of the courts.

There are a number of bars to rescission:

-5-

Law 231 L 06

•

Affirmation of the contract (subject to Misrepresentation Act 1967 s.1(b))

•

Lapse of time - see Leaf v International Galleries [1950] 2 KB 86 (CA)

•

Impossibility of restitution

•

Interference with third party rights

•

Misrepresentation Act 1967 s.2(ii)

Affirmation of the Contract:

Long v Hoyd

The defendant sold a lorry said to be in "exceptional" condition. The plaintiff found

that the speedo was not working, that there was a spring missing, and that it would not

go in to top gear. The defendant knocked £100 off the cost of the lorry, and the

plaintiff decided to buy it. Then the plaintiff found that the dynamo ceased to work

and that the lorry only did 5 miles to the gallon. He phoned the defendant who paid

50% of the cost of the new dynamo. The next day the lorry broke down completely,

and was deemed unroadworthy, and the plaintiff demanded the right to rescind. The

court found that this was a case of innocent misrepresentation, as the representation

was not fraudulent at the time, and there was therefore no right to damages. Also

because the plaintiff had accepted 50% of the cost of he dynamo, he was deemed to

have waived his right to rescission - affirmed the contract.

Nowadays, this type of action would probably be brought under s.2(1).

Lapse of Time:

Leaf v International Galleries [1950] 2 KB 86 (CA)

Bought a painting, supposedly a "Constable". 5 years later, it was discovered to be a

forgery, so the plaintiff attempted to rescind the contract. The Court of Appeal said

that after acceptance of the good, there could not be rejection, and that the contract

could not be rescinded.

Fraudulent misrepresentation - time starts from when the fraud is discovered.

Innocent misrepresentation - time starts the when the misrepresentation was made.

-6-

Law 231 L 06

Impossibility of Restitution:

Rescinding a contract is sometimes impossible due t the good being changed for

example. E.g. a car being resprayed. Prior to the 1967 Act, the court simply said

sorry - no rescission possible, unless fraudulent.

Interference with Third Part Rights:

In the case of third party rights, if the subject matter of the contract to be rescinded

has been sold to a third party prior to notice of rescission being given then the their

party is a bona fide purchaser without notice and thus acquires good title to the goods.

Prompt action is required to avoid such problems. Rescission take effect when the

innocent party either institutes proceedings or gives notice to the other party.

For example: (here the misrepresentation is the rubber cheque)

car

Seller

chq bounces

resale

Buyer

3rd Party

Can S get his car back?

If S notifies B before resale - legal title doesn't pass to B⇒ can't pass to 3rd P

If S notifies B after resale - bona fide purchaser without notice

Car & Universal Finance v Caldwell [1964] 1 All ER 290

ii)

Damages

a) for fraudulent misrepresentation (or for the tort of deceit)

Doyle v Olby (Ironmongers) Ltd [1969] 2 All ER 122 (CA)

IN this case, damages were awarded to return the plaintiff back to the position he was

in before the contract. Tort measure of damages applied - would include all losses

that directly flowed from the misrepresentation. Does this include loss of π 's?

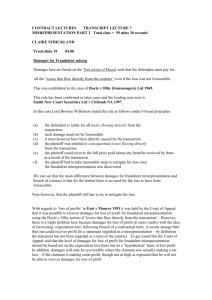

East v Maurer [1991] 2 All ER 733 (CA)

Bought a hair salon for £20,000. Representation that the defendant wouldn't work in

his other nearby salon. However, the seller did work in his other salon, and the

plaintiff had to sell his business for £7,500. Fraudulent misrepresentation. £33,000

damages for losses on business trading and sale. In addition, £15,000 awarded for

loss of π 's. The defendant appealed to the Court of Appeal over the £15,000, as he

-7-

Law 231 L 06

had given no guarantees about the π 's of the salon. However, he Court of Appeal

said that he loss of π 's could be recovered, since there had been deceit / fraud, but did

reduce the award to £10,000 on the basis that the fist court had used the wrong

method of calculation to calculate the damages.

Smith New Court Securities Ltd v Scrimgeour Vickers Ltd [1996] 4 All ER 769 (HL)

Sale / Purchase of shares.

Sale at 82.25p per share. Separate major fraud was discovered (3rd party), which put

the shares down to 44p each.

Q. What damages could be claimed?

82.25p? 78p (real value of share)? 10p (the difference)?

Claimed for 82.25p and 44p. Appeal Court said no - the difference between the price

paid and the actual price at that time.

House of Lords said that the Court of Appeal was correct in the normal method of

calculation, but on these facts, this wouldn't sufficiently compensate the plaintiff,

because they were locked into a contract that meant that they could not sell the shares

for a certain period of time. They said that all losses include the total, so they allowed

the whole amount.

There is confusion in this area, as tort and contract law seem to merge!

b) for negligent misrepresentation

Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd [1964] AC 465 (HL)

Misrepresentation Act 1967 s.2(i)

Under s.2(1) - damages should be the same as those for the tort of fraud. Could

eliminate claims for fraudulent misrepresentation? Damages have the potential to be

larger than under Hedley Byrne, but the courts may well impose lower damages.

Currently, providing that the misrepresentation has caused damages, this results in the

same damages as for fraud and negligence, but only at Court of Appeal Level, also,

fraud is harder to prove and does open up the possibility of criminal charges being

brought.

-8-

Law 231 L 06

Royscroft Trust Ltd v Rogerson [1991] 3 All ER 294 (CA)

Doubts have been expressed about this case, and the House of Lords may go against

this decision.

Gran Gelato Ltd v Richcliff (Group) Ltd [1992] 1 All ER 865

Failure to mention redevelopment - break clause.

The prospective lessor entered the contract and then found out, and claimed negligent

misrepresentation under s.2(1).

Plaintiff could have brought an action under either s.2(1) or Hedley Byrne.

The defence said that the plaintiff was contributory negligent, therefore the damages

should be reduced by a certain percentage. (Prior to 1945, proving this would have

lead to the case being wiped). The court said that the plaintiff should have checked

these clauses out, and so reduced the damages awarded.

Note that in cases involving fraud, contributory negligence cannot be used - see

Alliance & Leicester Building Society v Edgestop Ltd.

c) for innocent misrepresentation (non-fraudulent)

Misrepresentation Act 1967 s.2(ii)

Gives the courts very considerable discretion - damages may be awarded instead of

rescission for innocent misrepresentation if it is equitable to do so.

William Sindall plc v Cambridgeshire CC [1994] 3 All ER 932 (CA)

Sale of property for development. There was an underground sewer, of which the

local authority was unaware. Innocent misrepresentation. The court said that to

rescind the contract would have a catastrophic effect, and that it was therefore more

appropriate to award damages instead of rescission.

s.2(3) - damages limited (i.e. no "double" compensation), loss of π 's not covered.

Thomas Witter Ltd v TBP Industries Ltd [1996] 2 All ER 573

Can a court award damages after a bar to rescission has come into place? Obiter

comments say - yes, providing that you have had a right tot rescind at some point in

time. (This was based on Pepper & Harte)

note the distinction between damages and indemnity

-9-

Law 231 L 06

Whittington v Seals-Hayne (1900) 82 LT 49

Mistake

Mistake covers a variety of very different types of situation, many of which could be

dealt with under separate common law rules. The two main types of situation are,

firstly, where the parties are at cross-purposes as to what they have agreed and it is

impossible to ascertain the nature of the objective agreement. This can be a genuine

mistake of both parties or one party may know of the other's mistaken assumption

(unilateral mistake). Secondly, there is the situation where both parties had a shared

or common understanding which has been discovered after objective agreement has

been reached (common mistake).

Example:

Car

Seller

rd

Buyer

Cheque Bounces

3 Party

("Rogue")

(Bona fide

purchaser

minus notice)

Mistake as to the creditworthiness of the buyer.

If the seller notifies the buyer before third party takes "Ownership", then he still has

rights over the car.

If the car is passed on before notice is given, then the buyer "did" have legal

ownership, and third party is a Bona fide purchaser minus notice (BFP-N).

If a mistake and the court accepts this, then the seller-buyer contract is declared void

⇒ legal ownership never went to the buyer. So, legal case by seller against third

party. Both are "innocent". Ownership remains with the seller. Either way, it is not

fair!

Courts say "non-operative" mistake - third party keeps car, seller loses out. I.e. the

seller should have been more careful!

i)

"Agreement" Mistake

A party to a contract may find that he has contracted under some mistake as to a

crucial element of the contract such as the identity of the other party, the subject

matter of the contract, or the terms of the contract. Mistake as to identity has

occupied the courts on a number of occasions (note the overlap with fraud and

misrepresentation). Where the courts hold such a mistake to be operative, recognition

- 10 -

Law 231 L 06

is being given to the fact that the parties have never reached a true agreement, due to

the mistaken assumption as to a material fact on the party of the mistaken party. This

is often called "unilateral mistake". Due to the drastic nature of the effect of finding a

mistake to be operative - rendering the contract void - the courts have been less than

enthusiastic about doing so and the doctrine has a limited application.

Smith v Hughes (1871) LR 6 QB 597

Sold oats to the defendant, following an inspection of the oats. Described as "new

oats". Defendant thought he had contracted to buy "old oats". Defendant refused to

pay, arguing that there had been a mistake. Court said - there had been no mistake,

sine the defendant had inspected the oats before entering in to the contract.

Ingram v Little [1961] 1 QB 31 (CA)

Car sale - Bouncing Cheques - Lord Denning

Two old ladies sold a car to "Hutchinson". There was a "Hutchinson" in the 'phone

book, so they accepted a cheque from him. It bounced - hence "no payment".

"Hutchinson" then sold the car to the defendants. But - were the defendants bona fide

purchasers minus notice (BFP-N) … or … should the contract be declared void? Lord

Denning took sympathy on the old ladies - he said that they were only interested in

selling the car to "Hutchinson" - this was the "key factor", and they had checked the

'phone book to ascertain the identity of "Hutchinson". Hence - operative mistake⇒

sale to "Hutchinson" void ⇒ car still belonged to the old ladies!

Lewis v Avery [1972] 1 QB 198 (CA)

Advertised a car for sale. "Richard Green" agreed to pay. They believed that he was

a TV star, and he had ID to say he was. Cheque bounced, he disappeared. He sold

the car on to Avery. Case - no legal title passed. Court of Appeal said that the

contract between Lewis and Green was voidable by fraud ⇒ could be rescinded. But

… at the time of resale the cheque had not bounced. Intervention of third party rights

- bar to rescission. So Lewis argued mistake as well - he said that the identity of he

person he sold the car to was a key factor of the sale. The Court of Appeal said sorry - just a mistake as to the quality of the contract → not normally operative ⇒

contract not void for mistake.

Seller loses out - contradicts Ingham v Little - Second case seems fairer?

- 11 -

Law 231 L 06

ii)

"Possibility Mistake"

A different type of mistake is where the parties were in objective agreement but both

were mistaken as to some underlying fact which renders the purpose of he contract

impossible to achieve. These "possibility" mistakes include mistake as to the

existence of the subject matter - "res extincta", mistake as to ownership - "res sua",

and occasionally mistake as to quality. These are all referred to as "common

mistake".

Associated Japanese Bank v Credit du Nord [1988] 3 All ER 902

Comments are mostly obiter

Cooper v Phibbs (1867) LR 2 HL 149

Who owned what?

Cooper agreed to lease a salmon fishery from Phibbs. Cooper was already entitled to

the fish, because he already had a life tenancy. Therefore no need for lease. Phibbs

had no right to grant the lease - common mistake over ownership of the subject matter

⇒ contract inoperative ⇒ void!

Leaf v International Galleries [1950] 2 KB 86 (CA)

Leaf bought a painting - thought it was a Constable of Salisbury Cathedral. Actually,

five years later, it was discovered to be a forgery. Court of Appeal said misrepresentation - failed due to lapse of time - no fraud. Alternatively, Leaf claimed

mistake by both parties as to the quality of the subject matter of the contract. Court

said that it was a painting of Salisbury Cathedral - view taken that quality not

regarded as voidable. But, implied conditional term? ⇒ repudiation, but not argued.

Attempts have been made to formulate a test to determine when mistakes as to quality

would be operative. The test appears to require that the new facts must have so

altered from the original (Assumed) facts that the identity of the subject matter is no

longer the same, arguably resulting in a failure of consideration due to it being

impossible to perform the contract as originally agreed. On occasion it will be

difficult to distinguish, on the facts, between a mistake as to quality and a mistake as

to the subject matter, at least where the quality in question is fundamental to the

nature of the subject matter. Whatever the precise wording of the test, establishing

- 12 -

Law 231 L 06

that a mistake as to quality is operative, and thus that the contract is void, is extremely

difficult and a rare occurrence.

Bell v Lever Bros [1932] AC 161 (HL)

Bell was paid £30,000 - golden handshake - terminate contract of employment.

Unknown to either party, Bell and colleague had been in other activities in breach of

existing contract. When this came to light, Lever Bros. said mistake as to position of

Bell and colleague ⇒ contract of £30,000 should be declared void as there had been a

mistake as tot he quality of the contract. Both the trial judge and the Court of Appeal

agreed, but the House of Lords decided (on a 3:2 majority) that there had been no

operative mistake ⇒ contract not void ⇒ Bell keeps the money. Lord Atkin, in the

leading judgement, said that a mistake as to quality, if operative mistake, must go to

the core of the contract → failure of consideration? → not void for mistake

What factors will ever pass this test, if any?!

iii)

Common Law and Equitable Remedies

Where the mistake relates to he quality of he subject matter, this test has proved

difficult to apply. In response, it has been suggested that a doctrine of equitable

mistake existed alongside the common law doctrine which provided greater

flexibility. If this view is accepted, the effect is to render a contract voidable and

enable the court to set it aside after imposing new terms on the parties. Recognition

of this view is found, at first instance, in a recent case on the topic which also

provides a review of earlier authorities.

Solle v Butcher [1950 1 KB 671 (CA)

Lease of a flat - 7 years - £250 per year rent. Both believed flat not subject to any

statutory rent control. Mistake on both parts - there was a maximum of £140 per year.

Solle sought to recover excess paid. Defendant counterclaimed - contract void for

mistake. Court of Appeal said Solle had a choice - surrender altogether or pay the full

rent. But equitable doctrine if mistake as well - Denning.

This judgement has never been overruled, but is highly questionable!

Associated Japanese Bank v Credit du Nord [1988] 3 All ER 902

Steen seems to have endorsed this.

- 13 -

Law 231 L 06

Four machines were sold to the Associated Japanese Bank by X. Contract for sale

with a leaseback contract. Guarantors were Credit du Nord. X defected on his

payments. On investigation, AJB discovered that the machines did not exist. X

declared bankrupt. So, AJB sought recovery from Credit du Nord, using two

arguments - 1) condition precedent - upheld by Justice Steen - condition precedent

implies existence, but they did not ⇒ contract never in existence, 2) guarantee given

was void from the outset on the grounds of mistake - accepted as well.

So, is this a question of subject matter or quality? Existence. Quality - Steen treated

as if it were this.

These developments will only apply where there has been no allocation of the risks by

the parties themselves.

If void at common law, can we consider the equity of the case?

William Sindall plc v Cambridgeshire CC [1994] 3 All ER 932 (CA)

First of all, look at the terms of the contract - which party "accepted" the risk?

Had considered risk → didn't bring in mistake.

- 14 -