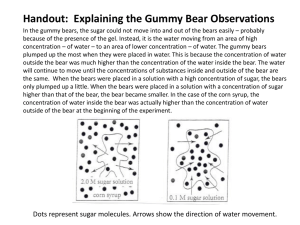

black bear management plan - Division of Fish and Wildlife

advertisement