EMS Response to Domestic Violence

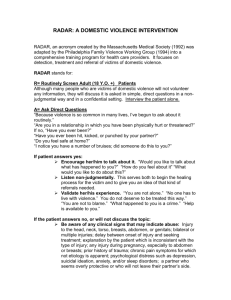

advertisement