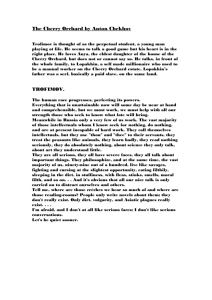

before seeing the performance…

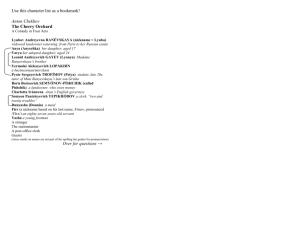

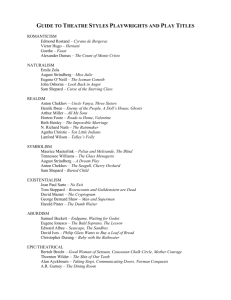

advertisement