Relationships Among Goals and Flirting: A Recall Study by

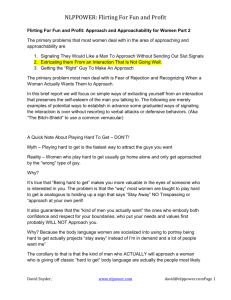

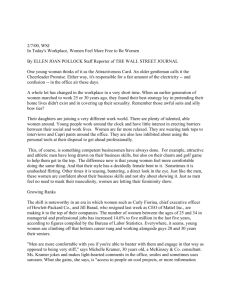

advertisement