Phineus

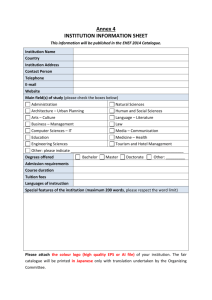

advertisement

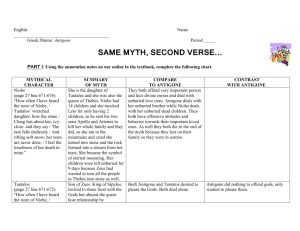

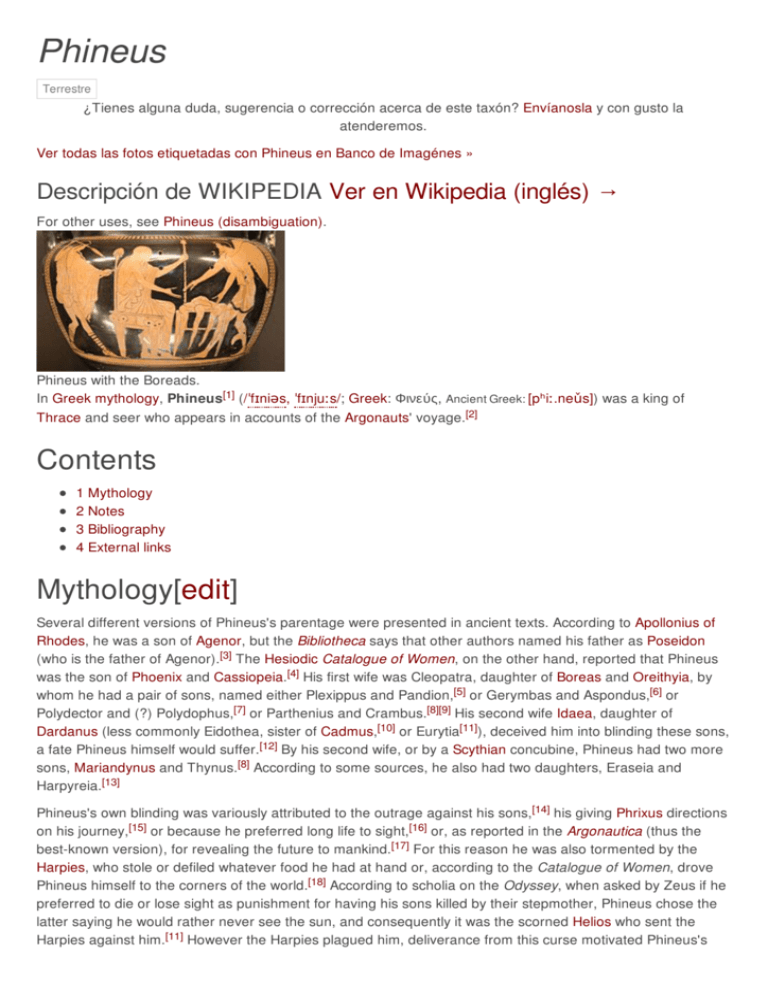

Phineus ¿Tienes alguna duda, sugerencia o corrección acerca de este taxón? Envíanosla y con gusto la atenderemos. Ver todas las fotos etiquetadas con Phineus en Banco de Imagénes » Descripción de WIKIPEDIA Ver en Wikipedia (inglés) → For other uses, see Phineus (disambiguation). Phineus with the Boreads. In Greek mythology, Phineus[1] (/ˈfɪniəs, ˈfɪnjuːs/; Greek: Φινεύς, Ancient Greek: [pʰiː.neǔs]) was a king of Thrace and seer who appears in accounts of the Argonauts' voyage.[2] Contents 1 2 3 4 Mythology Notes Bibliography External links Mythology[edit] Several different versions of Phineus's parentage were presented in ancient texts. According to Apollonius of Rhodes, he was a son of Agenor, but the Bibliotheca says that other authors named his father as Poseidon (who is the father of Agenor).[3] The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women, on the other hand, reported that Phineus was the son of Phoenix and Cassiopeia.[4] His first wife was Cleopatra, daughter of Boreas and Oreithyia, by whom he had a pair of sons, named either Plexippus and Pandion,[5] or Gerymbas and Aspondus,[6] or Polydector and (?) Polydophus,[7] or Parthenius and Crambus.[8][9] His second wife Idaea, daughter of Dardanus (less commonly Eidothea, sister of Cadmus,[10] or Eurytia[11]), deceived him into blinding these sons, a fate Phineus himself would suffer.[12] By his second wife, or by a Scythian concubine, Phineus had two more sons, Mariandynus and Thynus.[8] According to some sources, he also had two daughters, Eraseia and Harpyreia.[13] Phineus's own blinding was variously attributed to the outrage against his sons,[14] his giving Phrixus directions on his journey,[15] or because he preferred long life to sight,[16] or, as reported in the Argonautica (thus the best-known version), for revealing the future to mankind.[17] For this reason he was also tormented by the Harpies, who stole or defiled whatever food he had at hand or, according to the Catalogue of Women, drove Phineus himself to the corners of the world.[18] According to scholia on the Odyssey, when asked by Zeus if he preferred to die or lose sight as punishment for having his sons killed by their stepmother, Phineus chose the latter saying he would rather never see the sun, and consequently it was the scorned Helios who sent the Harpies against him.[11] However the Harpies plagued him, deliverance from this curse motivated Phineus's [19] involvement in the voyage of the Argo.[19] When the ship landed by his Thracian home, Phineus described his torment to the crew and told them that his brothers-in-law, the wing-footed Boreads, both Argonauts, were fated to deliver him from the Harpies.[20] Zetes demured, fearing the wrath of the gods should they deliver Phineus from divine punishment, but the old seer assured him that he and his brother Calais would face no retribution.[21] A trap was set: Phineus sat down to a meal with the Boreads standing guard, and as soon as he touched his food the Harpies swept down, devoured the food and flew off.[22] The Boreads gave chase, pursuing the Harpies as far as the "Floating Islands" before Iris stopped them lest they kill the Harpies against the will of the gods.[23] She swore an oath by the Styx that the Harpies would no longer harass Phineus, and the Boreads then turned back to return to the Argonauts. It is for this reason, according to Apollonius, that the "Floating Islands" are now called the Strophades, the "Turning Islands".[24] Phineus then revealed to the Argonauts the path their journey would take and informed them how to pass the Symplegades safely, thus filling the same role for Jason that Circe did for Odysseus in the Odyssey.[19] A now lost play about Phineus, Phineus, was written by Aeschylus and was the first play in the trilogy that included The Persians, produced in 472 B.C.[25] Notes[edit] 1. ^ The name is occasionally rendered "Phineas" in popular culture, as in the film Jason and the 2. 3. 4. 5. Argonauts. "Phineus" may be associated with the ancient city of Phinea (or Phineopolis) on the Thracian Bosphorus.[citation needed] ^ Bremmer (1996), Dräger (2007). ^ Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 2. 236–7; Bibliotheca 1. 9. 21 ^ Catalogue fr. 138 (Merkelbach & West 1967). ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3. 15. 3 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. ^ Scholia on Sophocles, Antigone, 981, 989 ed. Brunck ^ Scholia on Ovid, Ibis, 273 ^ a b Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 2. 140 ^ Dräger (2007) ^ Scholia on Sophocles, Antigone, 989 ^ a b Scholia on Odyssey, 12. 69 ^ Scholia to Argonautica 2.178; cf. Sophocles, Antigone 966–76. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. ^ Tzetzes, Chiliades, 1. 220; on Lycophron 166 ^ Sophocles fr. 704 Radt ^ Megalai Ehoiai fr. 254 (Merkelbach & West 1967). ^ Catalogue of Women fr. 157 (Merkelbach & West 1967). ^ Apollonius, Argonautica 2. 178–86. ^ Phineus' food: Argonautica 2. 187–201; his wandering torment: Catalogue of Women fr. 151 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. (Merkelbach & West 1967). ^ a b Dräger (2007). ^ Apollonius, Argonautica 2. 234–9. ^ Apollonius, Argonautica 2. 244–61. ^ Apollonius, Argonautica 2. 263–72. ^ Apollonius, Argonautica 2. 282–7. ^ Apollonius, Argonautica 2. 288–97. 25. ^ Thomson, G. (1973). Aeschylus and Athens (4 ed.). Lawrence & Wishart. p. 279. Bibliography[edit] Bremmer, J.N. (1996), "Phineus", in S. Hornblower & A. Spawforth (eds.), Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd rev. ed.), Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-866172-6. Dräger, P. (1993), Argo Pasimelousa. Der Argonautenmythos in der griechischen und römischen Literatur. Teil 1: Theos aitios, Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3-515-05974-9. Dräger, P. (2007), "Phineus", in H. Cancik & H. Schneider (eds.), Brill's New Pauly: Antiquity, 11 (Phi– Prok), ISBN 978-90-04-14216-9. Merkelbach, R.; West, M.L. (1967), Fragmenta Hesiodea, Oxford, ISBN 0-19-814171-8. West, M.L. (1985), The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women: Its Nature, Structure, and Origins, Oxford, ISBN 0-19-814034-7. External links[edit] Media related to Phineus at Wikimedia Commons Authority control GND: 1036917665