Money market reform and the short end of the bond market

advertisement

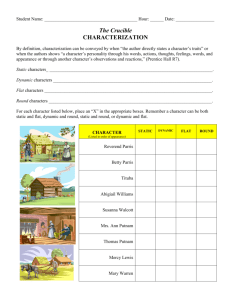

March 2015 » White paper Bonds or bond funds? reform and the Why Money a bond fundmarket might be the better choice for most clients short end of the bond market Michael V. Salm Co-Head of Fixed Income Jo Anne Ferullo, CFA Senior Investment Director Joanne M. Driscoll, CFA Portfolio Manager Key takeaways The transformation of U.S. money markets •New Rule 2a-7 money market reforms were enacted by the SEC in 2014 to address concerns regarding potential “runs” on money market funds. •The new reforms mandate tests and triggers for redemption fees and gates, among other measures. •As the regulations are implemented, volatility at the short end of the yield curve may increase as retail and institutional investors recognize the relative attractiveness of government money market funds without any fees and gates. Recent money market reform, as well as the ongoing process of systemic regulatory change in the nation’s financial infrastructure, is having an impact on the overall liquidity of U.S. markets, much of which is squarely focused on the front end of the U.S. Treasury yield curve. In this first paper of a two-part series, we examine the market conditions that primarily motivated recently enacted money market reform and outline the key changes embedded in these new rules, including any potential downstream market effects that we think they may be likely to cause. After several years of debate, the most recent set of money market reform measures were finally voted into reality in the summer of 2014. On July 23, 2014, the SEC approved final rules that amend Rule 2a-7, the governing regulation for money market funds. A narrow 3–2 vote set in motion the implementation of rules that had been under debate for several years. The rules became effective October 13, 2014. The implementation period is staggered from nine months to two years. This long time frame is certainly needed as market participants have nearly 1,000 pages of rule changes to digest and implement, including in investor disclosures and educational material, on web-based platforms, and within fund providers’ internal systems. Money markets in crisis The rule changes were enacted in order to protect money market funds, and thus the financial markets, from a potential “run” if there is another crisis similar to that which we experienced beginning in 2007. The credit crisis primarily manifested itself in the short end of the market in two ways: first, with investors backing away from the asset-backed commercial paper (“ABCP”) market, and second, when the Reserve Primary Fund “broke the buck” as a direct result of the Lehman bankruptcy on September 15, 2008, and the subsequent price markdown of its Lehman debt holdings. PUTNAM INVESTMENTS | putnam.com FOR USE WITH INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS AND INVESTMENT PROFESSIONALS MARCH 2015 | Money market reform and the short end of the bond market Commercial paper under pressure Interestingly, retail funds saw net inflows during this time as retail investors sought safety, while it was the prime institutional money market funds that experienced over $170 billion in net outflows from September 15 to 17, 2008. The majority of that outflow moved into government institutional money market funds. This is the key reason why the new 2a-7 rules differentiate between the retail and the institutional investor, and are imposing the floating NAV on institutional money market funds rather than retail funds. Various types of ABCP came under extreme pressure in the summer of 2007 after two Bear Stearns hedge funds that invested in subprime mortgages filed for bankruptcy. Shortly thereafter, three BNP Paribas assetbacked bond funds* suspended redemptions due to their inability to adequately assess the value of the mortgages (approximately one third of the funds were invested in subprime) and other investments held by those funds. ABCP may be backed by a variety of collateral (e.g., trade receivables); in 2007, some ABCP deals were also backed by subprime mortgages. As a consequence of the Bear Stearns and BNP Paribas events, investors generally moved away from the ABCP market broadly, regardless of collateral type, which triggered substantial credit and liquidity pressures in that market. From August 2007 to August 2008, the amount of ABCP outstanding fell from $1.2 trillion to $745 billion — a 37% decline1 as these short-term instruments matured and were not renewed (“rolled over”) as would normally have been the case. Commercial paper is a corporate linchpin Beyond these more obvious impacts is the trickle-down effect that a run on money market funds could precipitate. Money market funds are the primary buyers of CP. If there is a run on the money market fund system, money market funds will be working to raise cash, not invest it. Commercial paper debt is issued by many companies in order to fund themselves over short time periods, typically no longer than 270 days, or about nine months. Those funding needs tend to be fairly consistent, so companies will simply “roll over” their CP — when the security reaches maturity, a new one is immediately issued, effectively rolling that debt to a new maturity date in the future. In a liquidity event, money market funds could pull away from the CP market and, left without the cash on hand to pay off their short-term CP debt, companies will be faced with a lack of liquidity and will need to turn to other sources. The buck breaks In September 2008, under severe pressure from the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, the Reserve Primary Fund — the oldest U.S. money market fund — saw the net asset value (“NAV”) of its shares fall to 97 cents from the supposedly rock-solid $1.00 NAV. This was the second major crisis-driven event to impact the short end of the market. This announcement drove a wave of highly publicized redemptions by jittery institutional investors from money market funds and short-term funds, which were forced to liquidate assets or impose limits on redemptions. Even though the U.S. government decided to provide deposit insurance to investments in money market funds and the flood of redemptions slowed drastically, many money market funds chose to reduce their holdings of any traditional commercial paper (“CP”) they believed their investors might perceive as too risky. By mid-October 2008, what had been $1.8 trillion outstanding in CP fell by 15% to $1.43 trillion.2 This precipitous decline in the CP market was halted only when the Federal Reserve began purchasing commercial paper directly from CP issuers. PUTNAM INVESTMENTS | putnam.com Many companies have bank lines of credit to fall back on, but these are more expensive and have limitations on the amount that may be drawn. Companies without backup sources of liquidity (or whose liquidity needs exceed their backup facility) and with no way to quickly raise money, may default on their CP debt and/or other short-term obligations. Without short-term funding or readily liquid assets on hand, the companies may have to declare bankruptcy. Given the widespread use of CP for short-term funding (in early 2007, before the crisis, there was $1.97 trillion in outstanding CP3), the potential exists for significant bankruptcies to occur, creating a downward spiral and serious economic damage. 2 PUTNAM INVESTMENTS | putnam.com Post-crisis regulations: The first wave of change The third significant liquidity requirement was the change in the allowable level of credit quality; this reduced the amount permitted to be purchased of what is referred to as Tier 2 or A-2/P-2 rated (roughly equated to BBB) securities to 3% of net assets versus what had originally been 5%. This quality limitation has created a dislocation between the higher-rated money-marketfund-eligible securities and short-dated BBB-rated securities — a potential opportunity for gaining additional yield for funds not managed under Rule 2a-7. In 2010, the SEC made their first round of changes to Rule 2a-7 in response to the impacts of the credit crisis. This initial set of rule changes were intended to hone in on increasing the resiliency of money market funds to economic stresses. We believe that, among the changes made at that time, the most important updates were ensuring that money market funds maintained a high degree of liquidity and highlighting the “shadow,” or market value, NAV of a money market fund. Lastly, stress testing was required for the actual market value (or “shadow”) NAV of money market funds, which represents what the fund’s NAV would be if its securities were priced according to market value as opposed to amortized cost pricing. The goal of stress testing is to measure a money market fund’s ability to maintain a $1.00 NAV in the event of shocks to the market. The stress testing is meant to identify the potential for any one money market fund to “break the buck,” or fail to provide investors with transactions valued at $1.00 NAV. Additionally, the actual shadow NAV was also required to be reported to the SEC and then made available to the public 60 days later. This requirement put a bright light on the shadow, or market value, NAV of a money market fund, which many typical investors were not even aware existed. Shorter WAM, higher liquidity, stress testing With the goal of ensuring liquidity, the SEC insisted on three points. The first focused on the weighted average maturity (“WAM”) of money market funds. The SEC under Rule 2a-7 has always proscribed the WAM of a money market fund; before the 2010 changes, it was 90 days. The new change mandated the WAM to be no longer than 60 days. While a one-month change, as interpreted by the casual observer, may not seem to matter much, it was a significant change for money market funds because it reduced the WAM by 33%. Figure 1. Weighted average maturity (days) 90 Pre Rule 2a-7 Post Rule 2a-7 Post-crisis regulations: The second wave of change 60 The new SEC 2014 changes for Rule 2a-7 allow the potential implementation of redemption fees and gates should a money market fund’s weekly assets fall below the 30% threshold. This is intended to stem the tide of potential redemptions for retail and institutional non-government money market funds in times of market stress, helping to ensure that money market funds do not retreat from the market en masse. By allowing fees and gates, the mechanism is in place for money market fund Boards to opt to reduce the amount of redemptions by imposing a fee, thereby creating a deterrent for investors to redeem, and/or to halt redemptions for a specific period of time, thereby enabling money market funds to avoid becoming forced sellers into a deteriorating market. Source: Securities and Exchange Commission. The second point was the brand new provision mandating liquidity requirements that now specified that money market funds maintain a minimum of 10% in daily liquidity and that 30% of the fund must be liquid within seven days (certain securities with longer maturities also meet the criteria). The updated WAM and new liquidity requirements pushed money market fund demand even shorter on the yield curve, which has added to the downward pressure on the level of yields for shorter maturities. 3 MARCH 2015 | Money market reform and the short end of the bond market Redefining money market funds the two-decimal $1.00 NAV; likewise, if a tax-exempt money market fund is deemed institutional, it will transact using a four decimal NAV. The amendments addressed three major topics of concern as well as updated a number of other areas of the regulation. The three major topics are 1) officially defining various types of money market funds, 2) requiring a floating NAV for certain “non-retail” money market funds, and 3) allowing the imposition of redemption fees and gates. While not all the rules impact every type of money market fund in exactly the same way, all money market funds will be affected by the latest cycle of changes. 3.Redemption fees and gates Money market funds are required to maintain 30% in weekly liquid assets (i.e., assets maturing in seven days or less). There are two types of redemption fee scenarios that apply to both retail and institutional money market funds, though not to government money market funds unless they opt in and have disclosed that choice in a prior prospectus. 1. Money market fund definitions a.Retail funds: The new rules define a “retail” money market fund to be a fund with policies reasonably designed to limit its investors solely to “natural persons.” The fund industry will be working with the SEC to provide further definition for the categories of investors eligible to invest in “retail” funds. a.If the money market fund’s weekly liquidity falls below the required 30%, the fund’s Board has the discretion to impose a maximum 2% redemption fee if it decides it is in the best interest of the fund to do so. b.Additionally, if the weekly liquidity falls below 10% there is a default redemption fee of 1% that is imposed automatically unless the fund’s Board decides it is in the fund’s best interest to not impose that fee or to impose a higher fee of up to 2%. Once the 30% weekly liquid asset test is again met, the fees automatically stop. b.Institutional funds: Non-retail, or institutional, funds are defined as funds with beneficial owners who are not “natural persons” but entities, such as corporations, partnerships, certain trust structures, etc. c.Retail and institutional tax-exempt funds: Tax-exempt money market funds will also follow the retail versus institutional rules. A gate means that a fund temporarily suspends redemptions. If the fund’s weekly liquidity falls below 30% and remains below 30% for up to 10 business days, the fund’s Board may temporarily suspend redemptions if it determines that it is in the best interest of the fund. The gate may only be imposed for the shorter of 10 days or until the weekly liquidity returns to at least 30%. The gate may only be used for up to 10 days during any 90-day period. This is applicable to both retail and institutional money market funds, although not to government money market funds unless they opt in and have disclosed that choice in a prior prospectus. d.Government funds: The new rules also define a “government” money market fund to be a fund with 99.5% of its assets invested in cash, U.S. government securities, and/or repurchase agreements that are collateralized by U.S. government securities. 2.Floating NAV Under the new rule, only retail and government money market funds may utilize the rounded two-decimal NAV, which under normal circumstances allows a fund to maintain a stable $1.00 NAV. Non-retail funds (other than government funds) will be required to use a four-decimal NAV. The additional two decimal points Additional second-wave changes Beyond these major changes, a number of other changes refining diversification, disclosure, and stress testing (among others) are also being implemented. Depending on the change, the implementation period may range from nine months to two years from the October 2014 effective date. The three major changes outlined above are to be implemented in two years. eliminate the ability of institutional non-government funds to strike a $1.00 NAV; their NAV will float based on the four-decimal NAV. If a tax-exempt money market fund is deemed to be retail, it may continue to maintain PUTNAM INVESTMENTS | putnam.com 4 PUTNAM INVESTMENTS | putnam.com The regulatory transformation of money market funds Fund differentiation Prime institutional Retail Government (retail or institutional) Tax exempt (retail or institutional) Definition No “natural persons”; only institutions Beneficial owners limited to “natural persons” 99.5% invested in cash, government securities, 100% governmentcollateralized repo Institutional and retail definitions apply Floating NAV Floating $1.00 $1.00 Institutional and retail definitions apply Redemption fee Based on weekly liquidity: Based on weekly liquidity: Based on weekly liquidity: If <30%, max 2% fee at board discretion If <30%, max 2% fee at board discretion May opt in with prior prospectus disclosure If <10%, 1% fee required, unless board removes or increases up to 2% If <10%, 1% fee required, unless board removes or increases up to 2% Based on weekly liquidity: If <30%, board may suspend up to 10 days Based on weekly liquidity: If <30%, board may suspend up to 10 days Gates If <30%, max 2% fee at board discretion If <10%, 1% fee required, unless board removes or increases up to 2% May opt in with prior prospectus disclosure Based on weekly liquidity: If <30%, board may suspend up to 10 days All funds are required to comply with new disclosure and reporting, diversification, and stress testing requirements. Anticipated market impacts their assets into a suitable money market fund, while others may consider the broader universe of the growing category of ultra-short funds. A number of investors may choose to redeploy assets into completely different strategies outside of short-dated fixed-income assets. The splitting up of assets based on investor type may thus force potentially material fund flows, both within the money market fund universe and outside it. Consequently, these flows may amplify market volatility, depending on the magnitude of movement and the types of assets being traded. With a long transition period to implement the various reforms, the likelihood of significant market change in the near term is low. However, over time the short end of the market may become markedly different from how it is today. Some effects engendered by reform will be fairly obvious — such as greater demand for government securities — while others will be more subtle, such as the potential flow effect related to increased disclosure of fund liquidity. The first and most obvious impact of the reform stems from the definition of the types of money market funds and the application of the floating NAV. Differentiating between retail and institutional investors in and of itself does not wreak havoc on the system. However, we believe that eliminating the floating NAV for institutional investors may create significant transitional effects. Fund companies will need to review their full investor base to differentiate their institutional versus retail investors, and will likely designate an existing money market fund as either retail or institutional. Those investors who do not fit within the designated definition of their current money market fund investment will need to redeem their shares and will be faced with a choice regarding a new investment for those assets. Some investors will move Additionally, with the definition of government money market funds changing, from maintaining at least 80% government assets to increasing that minimum level to 99.5%, it is clear there will be more demand for short-term government assets. Since 2008, with the exception of one year, U.S. Treasury bills outstanding have decreased each year. Combined, the decline in outstanding bills from 2009 through the end of 2014 is $404 billion. If institutional investors opt for government money market funds in order to maintain the $1.00 NAV, demand for short -term government assets would be even greater. Less supply and greater demand typically translates into lower yields, which will continue to pressure rates at the short end of the yield curve. 5 MARCH 2015 | Money market reform and the short end of the bond market Annual U.S. Treasury bill issuance and outstanding SIFMA year to date 12/31/14 (USD billions) Year Gross issuance Outstanding Change 1998 $759.1 $691.0 ­— 1999 — 737.1 $46.1 2000 1,725.4 646.9 -90.2 2001 2,362.5 811.2 164.3 2002 3,241.0 888.7 77.5 2003 3,503.3 928.8 40.1 2004 3,836.4 1,001.2 72.4 2005 3,615.7 960.7 -40.5 2006 3,632.7 940.8 -19.9 2007 3,742.3 999.5 58.7 2008 5,627.7 1,861.2 861.7 2009 6,417.7 1,793.5 -67.7 2010 6,099.7 1,772.5 -21.0 2011 5,401.7 1,520.5 -252.0 2012 5,623.8 1,629.0 108.5 2013 5,715.9 1,592.0 -37.0 2014 4,815.0 1,457.9 -134.1 Source: Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. Further, beyond the more obvious potential impacts, we must also consider the possible impact of increased disclosure for money market funds. While the revised disclosure requirements are not considered especially onerous or wrenching for the money market fund industry, it will be the first time that investors will be able to clearly see the amount of liquidity money market funds may be maintaining. Importantly, the money market fund industry will need to consider investor responses to these new requirements. There will almost certainly be issues given the additional demand for short-term assets and/or the potential for outflows when a fund begins to appear to be liquidity-challenged. Will investors opt to exit a money market fund showing levels of liquidity below 30% in an effort to avoid the potential imposition of fees or gates? Investors in aggregate may become wary of any developments that could materially reduce their ability to keep the entire balance of their assets upon redemption and/or impair their ability to exit at their desired time. PUTNAM INVESTMENTS | putnam.com 6 PUTNAM INVESTMENTS | putnam.com Conclusion If a disruptive market environment should create material outflows from money market funds, the possible implementation of fees or gates could certainly serve as an incentive for investors to flee the funds much earlier than they normally might. Armed with the knowledge that they could be hit with a fee or restricted by a gate that could significantly delay their exit, investors may opt to redeem sooner rather than later if they observe that liquidity at the fund level is close to being compromised. No one wants to be the last one out. In other words, the conditions set up by fee and gate structures could themselves precipitate the situation the SEC was attempting to avoid in the first place: a “run” on money market funds and the downstream pull back of money market funds from the CP market. This is a long-standing industry criticism of the SEC’s solution. In working to obviate the potential for massive redemptions from money market funds, the changes by the SEC to Rule 2a-7 have effectively steered more demand to the U.S. Treasury bill market and potentially increased the pace of redemptions from money market funds as investors may be inclined to exit before fees and gates are imposed. The greater demand for and reduced supply of Treasury bills is likely to suppress yields in the short end. Accelerating the pace of redemptions merely increases the probability of imposing fees and gates on investors. These dynamics could materially impact liquidity in important market segments like the CP market, which continues to be an important funding mechanism for companies. It remains to be seen how money market funds will react to extreme environments under the new regulation, but by all appearances, it could be highly challenging for investors and investment funds. If accelerated redemptions do occur, there will likely be other active market disruptions amid a serious riskoff environment. Significant market dislocation will push the limits of broader market liquidity, which already has materially changed over the past five years due to financial regulation and reform. In general, market strategists are concerned that the money market fund reform measures may have created a situation in which there is greater market sensitivity to potential liquidity events and a greater chance of market seizure. Endnotes 1BNP Paribas ABS Euribor Fund, BNP Paribas ABS Eonia Fund, and Parvest Dynamic ABS Fund. Footnotes 1. Marcin Kacperczyk and Philipp Schnabl, “When Safe Proved Risky: Commercial Paper during the Financial Crisis of 2007–2009,” vol. 24 number 1, Winter 2010, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29. 2. Kacperczyk and Schnabl, 30. 3. Kacperczyk and Schnabl, 30. 7 MARCH 2015 | Money market reform and the short end of the bond market This material is prepared for use by institutional investors and investment professionals and is provided for limited purposes. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument, or any Putnam product or strategy. References to specific asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or investment advice. The opinions expressed in this article represent the current, goodfaith views of the author(s) at the time of publication. The views are provided for informational purposes only and are subject to change. This material does not take into account any investor’s particular investment objectives, strategies, tax status, or investment horizon. The views and strategies described herein may not be suitable for all investors. Investors should consult a financial advisor for advice suited to their individual financial needs. Putnam Investments cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any statements or data contained in the article. Predictions, opinions, and other information contained in this article are subject to change. Any forward-looking statements speak only as of the date they are made, and Putnam assumes no duty to update them. Forward-looking statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks and uncertainties. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. This material is not directed at, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity that is a citizen or resident of or located in any jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability, or use would be contrary to applicable law or regulation or would subject any Putnam company to any registration or licensing requirement within such jurisdiction. The information is descriptive of Putnam Investments as a whole and certain services, securities, and financial instruments described may not be suitable for you or available in the jurisdiction in which you are located. This material or any portion hereof may not be reprinted, sold, or redistributed in whole or in part without the express written consent of Putnam Investments. The information provided relates to Putnam Investments and its affiliates, which include The Putnam Advisory Company, LLC and Putnam Investments Limited®. Issued in the United Kingdom by Putnam Investments Limited®. Putnam Investments Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). For the activities carried out in Germany, the German branch of Putnam Investments Limited is also subject to the limited regulatory supervision of the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht - BaFin). Putnam Investments Limited is also permitted to provide cross-border investment services to certain EEA member states. In Europe, this material is directed exclusively at professional clients and eligible counterparties (as defined under the FCA Rules, or the German Securities Trading Act (Wertpapierhandelsgesetz) or other applicable law) who are knowledgeable and experienced in investment matters. Any investments to which this material relates are available only to or will be engaged in only with such persons, and any other persons (including retail clients) should not act or rely on this material. This material is prepared by Putnam Investments for use in Japan by Putnam Investments Securities Co., Ltd. (“PISCO”). PISCO is registered with Kanto Local Finance Bureau in Japan as a financial instruments business operator conducting the type 1 financial instruments business, and is a member of Japan Securities Dealers Association. This material is prepared for informational purposes only, and is not meant as investment advice and does not constitute any offer or solicitation in Japan for the execution of an investment advisory contract or a discretionary investment management contract. Prepared for use with wholesale investors in Australia by Putnam Investments Australia Pty Limited, ABN,50 105 178 916, AFSL No. 247032. This material has been prepared without taking account of an investor’s objectives, financial situation, and needs. Before deciding to invest, investors should consider whether the investment is appropriate for them. Prepared for use in Canada by Putnam Investments Canada ULC (o/a Putnam Management in Manitoba). Where permitted, advisory services are provided in Canada by Putnam Investments Canada ULC (o/a Putnam Management in Manitoba) and its affiliate, The Putnam Advisory Company, LLC. Putnam Investments| One Post Office Square | Boston, MA 02109 | putnam.com 292521 3/15