Improving Student Learning Through Differentiated Instruction

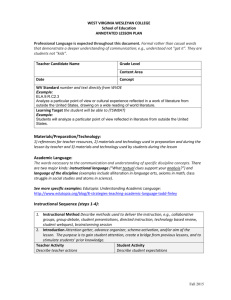

advertisement