UNDERSTANDING BY

DESIGN® FRAMEWORK

BY JAY MCTIGHE AND

GRANT WIGGINS

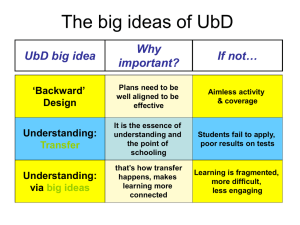

INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS UbD™ FRAMEWORK?

The Understanding by Design® framework (UbD™ framework) offers a planning process and structure to guide curriculum, assessment, and instruction. Its

two key ideas are contained in the title: 1) focus on teaching and assessing for

understanding and learning transfer, and 2) design curriculum “backward” from

those ends.

The UbD framework is based on seven key tenets:

1.Learning is enhanced when teachers think purposefully about curricular planning. The UbD framework helps this process without offering a rigid process

or prescriptive recipe.

2.The UbD framework helps focus curriculum and teaching on the development and deepening of student understanding and transfer of learning

(i.e., the ability to effectively use content knowledge and skill).

3. Understanding is revealed when students autonomously make sense of and

transfer their learning through authentic performance. Six facets of understanding—the capacity to explain, interpret, apply, shift perspective, empathize, and self-assess—can serve as indicators of understanding.

W W W. A S C D . O R G

1703 North Beauregard Street

Alexandria, VA 22311-1714 USA

1-703-578-9600 or

1-800-933-2723

©2012 ASCD. All Rights Reserved.

4. Effective curriculum is planned backward from long-term, desired results

through a three-stage design process (Desired Results, Evidence, and

Learning Plan). This process helps avoid the common problems of treating

the textbook as the curriculum rather than a resource, and activity-oriented

teaching in which no clear priorities and purposes are apparent.

5. Teachers are coaches of understanding, not mere purveyors of content knowledge, skill, or activity. They focus on ensuring that learning happens, not just

teaching (and assuming that what was taught was learned); they always aim

and check for successful meaning making and transfer by the learner.

6. Regularly reviewing units and curriculum against design standards enhances curricular quality and effectiveness, and provides engaging and professional discussions.

7.The UbD framework reflects a continual improvement approach to student achievement and teacher craft. The results of our designs—student performance—inform

needed adjustments in curriculum as well as instruction so that student learning

is maximized.

The Understanding by Design framework is guided by the confluence of evidence

from two streams—theoretical research in cognitive psychology, and results of student

achievement studies. A summary of the key research that undergirds UbD framework

can be found at www.ascd.org under Research A Topic.

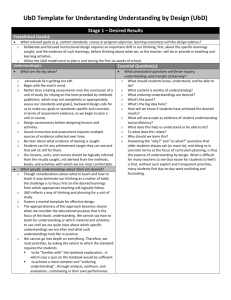

The Three Stages of

Backward Design

The UbD framework offers a three-stage

backward design process for curriculum

planning, and includes a template and set

of design tools that embody the process.

A key concept in UbD framework is alignment (i.e., all three stages must clearly

align not only to standards, but also to one

another). In other words, the Stage 1 content and understanding must be what is

assessed in Stage 2 and taught in Stage 3.

Stage 1—Identify Desired Results

Key Questions: What should students

know, understand, and be able to do?

What is the ultimate transfer we seek as a

result of this unit? What enduring understandings are desired? What essential

questions will be explored in-depth and

provide focus to all learning?

In the first stage of backward design, we

consider our goals, examine established

content standards (national, state, province, and district), and review curriculum

expectations. Because there is typically

more content than can reasonably be

addressed within the available time,

teachers are obliged to make choices.

This first stage in the design process calls

for clarity about priorities.

Learning priorities are established by

long-term performance goals—what it is

we want students, in the end, to be able

to do with what they have learned. The

bottom-line goal of education is transfer.

The point of school is not to simply excel

in each class, but to be able to use one’s

learning in other settings. Accordingly,

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 2

Stage 1 focuses on “transfer of learning.” Essential companion questions are used to

engage learners in thoughtful “meaning making” to help them develop and deepen

their understanding of important ideas and processes that support such transfer.

Figure 1 contains sample transfer goals and Figure 2 shows sample understandings

and essential questions.

FIGURE 1—SAMPLE TRANSFER GOALS

Discipline/Subject/Skill

Mathematics

Transfer Goals

• Apply mathematical knowledge, skill, and reasoning to solve real-world problems.

Writing

• Effectively write for various audiences to explain

(narrative, expository), entertain (creative), persuade (persuasive), and help others perform a

task (technical).

History

• Apply lessons of the past (historical patterns) to

current and future events and issues.

• Critically appraise historical claims.

Arts

• Create and perform an original work in a

selected medium to express ideas or evoke

mood and emotion.

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 3

FIGURE 2—SAMPLE UNDERSTANDINGS AND

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

Understandings

Essential Questions

Great literature explores universal themes of human existence

and can reveal truths through

fiction.

How can stories from other places and times

relate to our current lives?

Quantitative data can be

collected, organized, and

displayed in a variety of ways.

Mathematical ideas can be represented numerically, graphically, or symbolically.

What’s the best way of showing (or representing) ______________?

The geography, climate, and

natural resources of a region

influence the culture, economy,

and lifestyle of its inhabitants.

How does where we live influence how we

live?

The relationship between the

arts and culture is mutually

dependent; culture affects the

arts, and the arts reflect and

preserve culture.

In what ways do the arts reflect as well as

shape culture?

In what other way(s) can this be

represented?

Important knowledge and skill objectives, targeted by established standards, are also

identified in Stage 1. An important point in the UbD framework is to recognize that

factual knowledge and skills are not taught for their own sake, but as a means to larger

ends. Acquisition of content is a means, in the service of meaning making and transfer.

Ultimately, teaching should equip learners to be able to use or transfer their learning (i.e.,

meaningful performance with content). This is the result we always want to keep in mind.

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 4

Stage 2—Determine

Assessment Evidence

Key Questions: How will we know if students have achieved the desired results?

What will we accept as evidence of student understanding and their ability to use

(transfer) their learning in new situations?

How will we evaluate student performance

in fair and consistent ways?

Backward design encourages teachers

and curriculum planners to first think like

assessors before designing specific units

and lessons. The assessment evidence we

need reflects the desired results identified

in Stage 1. Thus, we consider in advance

the assessment evidence needed to

document and validate that the targeted

learning has been achieved. Doing so

invariably sharpens and focuses teaching.

In Stage 2, we distinguish between two

broad types of assessment—performance

tasks and other evidence. The performance tasks ask students to apply their

learning to a new and authentic situation

as means of assessing their understanding and ability to transfer their learning.

In the UbD framework, we have identified

six facets of understanding for assessment

purposes. When someone truly understands, they

• Can explain concepts, principles, and

processes by putting it their own words,

teaching it to others, justifying their

answers, and showing their reasoning.

• Can interpret by making sense of data,

text, and experience through images,

analogies, stories, and models.

• Can apply by effectively using and

adapting what they know in new and

complex contexts.

• Demonstrate perspective by seeing

the big picture and recognizing different points of view.

• Display empathy by perceiving

sensitively and walking in someone

else’s shoes.

• Have self-knowledge by showing

meta-cognitive awareness, using

productive habits of mind, and reflecting on the meaning of the learning

and experience.

Keep the following two points in mind

when assessing understanding through

the facets:

1. All six facets of understanding need

not be used all of the time in assessment. In mathematics, application,

interpretation, and explanation are the

most natural, whereas in social studies,

empathy and perspective may be added

when appropriate.

2. Performance tasks based on one or

more facets are not intended for use in

daily lessons. Rather, these tasks should

be seen as culminating performances for

a unit of study. Daily lessons develop the

related knowledge and skills needed for

the understanding performances, just as

practices in athletics prepare teams for

the upcoming game.

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 5

In addition to performance tasks, Stage 2

includes other evidence, such as traditional quizzes, tests, observations, and

work samples to round out the assessment picture to determine what students

know and can do. A key idea in backward

design has to do with alignment. In other

words, are we assessing everything that

we are trying to achieve (in Stage 1), or

only those things that are easiest to test

and grade? Is anything important slipping through the cracks because it is not

being assessed? Checking the alignment

between Stages 1 and 2 helps ensure

that all important goals are appropriately

assessed, resulting in a more coherent

and focused unit plan.

Stage 3—Plan Learning

Experiences and Instruction

Key Questions: How will we support learners as they come to understand important

ideas and processes? How will we prepare

them to autonomously transfer their learning? What enabling knowledge and skills

will students need to perform effectively

and achieve desired results? What activities, sequence, and resources are best

suited to accomplish our goals?

In Stage 3 of backward design, teachers

plan the most appropriate lessons and

learning activities to address the three

different types of goals identified in

Stage 1: transfer, meaning making, and

acquisition (T, M, and A). We suggest

that teachers code the various events

in their learning plan with the letters T,

M, and A to ensure that all three goals

are addressed in instruction. Too often,

teaching focuses primarily on presenting

information or modeling basic skills for

acquisition without extending the lessons

to help students make meaning or transfer the learning.

Teaching for understanding requires that

students be given numerous opportunities

to draw inferences and make generalizations for themselves (with teacher support). Understanding cannot simply be

told; the learner has to actively construct

meaning (or misconceptions and forgetfulness will ensue). Teaching for transfer

means that learners are given opportunities to apply their learning to new situations and receive timely feedback on

their performance to help them improve.

Thus, the teacher’s role expands from

solely a “sage on the stage” to a facilitator of meaning making and a coach giving

feedback and advice about how to use

content effectively.

SUMMARY

We have included a summary of the key

ideas in UbD framework as a figure (see

“UbD in a Nutshell”) in Appendix A at

the end of this paper. Also see “Learning

Goals and Teaching Roles” in Appendix B

for a detailed account of the three interrelated learning goals.

FREQUENTLY ASKED

QUESTIONS

Over the years, educators have posed the

following questions about the UbD framework. We provide brief responses to each

question and conclude with thoughts

about moving forward.

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 6

1. This three-stage planning

approach makes sense. So, why do

you call it “backward” design?

We use the term “backward” in two ways:

1. Plan with the end in mind by first clarifying the learning you seek—the learning

results (Stage 1). Then, think about the

assessment evidence needed to show that

students have achieved that desired learning (Stage 2). Finally, plan the means to

the end—the teaching and learning activities and resources to help them achieve

the goals (Stage 3). We have found that

backward design, whether applied by

individual teachers or district curriculum

committees, helps avoid the twin sins of

activity-oriented and coverage-oriented

curriculum planning.

2. Our second use of the term refers to

the fact that this approach is backward to

the way many educators plan. For years,

we have observed that curriculum planning often translates into listing activities

(Stage 3), with only a general sense of

intended results and little, if any, attention to assessment evidence (Stage 2).

Many teachers have commented that the

UbD planning process makes sense, but

feels awkward because it requires a break

from comfortable planning habits.

2. I have heard that the UbD

framework de-emphasizes the

teaching of content knowledge

and skill to focus on more general

understanding. Is this your

recommendation?

On the contrary, the UbD framework

requires that unit designers specify what

students will know and be able to do

(knowledge and skills) in Stage 1. However,

we contend that content acquisition is a

means, not an end. The UbD framework

promotes not only acquisition, but also the

student’s ability to know why the knowledge and skills are important, and how

to apply or transfer them in meaningful,

professional, and socially important ways.

3. Should you use the three-stage

backward design process and the

UbD template for planning lessons

as well as units?

Careful lesson planning is essential to

guide student learning. However, we do

not recommend isolated lesson planning

separate from unit planning. We have

chosen the unit as a focus for design

because the key elements of the UbD

framework—understandings, essential

questions, and transfer performance

tasks—are too complex and multifaceted to be satisfactorily addressed within

a single lesson. For instance, essential

questions are meant to be explored and

revisited over time, not answered by the

end of a single class period.

Nonetheless, the larger unit goals provide

the context in which individual lessons are

planned. Teachers often report that careful

attention to Stages 1 and 2 sharpens their

lesson planning, resulting in more purposeful teaching and improved learning.

4. What is the relationship between

the Six Facets of Understanding

and Bloom’s Taxonomy?

Although both function as frameworks

for assessment, one key difference is that

Bloom’s Taxonomy presents a hierarchy of

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 7

cognitive complexity. The taxonomy was initially developed for analyzing the demands

of assessment items on university exams.

The Six Facets of Understanding were

conceived as six equal and suggestive

indicators of understanding, and thus are

used to develop, select, or critique assessment tasks and prompts. They were never

intended to be a hierarchy. Rather, one

selects the appropriate facet(s) depending on the nature of the content and the

desired understandings about it.

5. I find it hard to use all Six Facets

of Understanding in a classroom

assessment. How can I do this?

We have never suggested that a

teacher must use all of the facets when

assessing students’ understanding. For

example, an assessment in mathematics

might ask students to apply their understanding of an algorithm to a real-world

problem and explain their reasoning. In

history, we might ask learners to explain

a historical event from different perspectives. In sum, we recommend that

teachers use only the facet or facets that

will provide appropriate evidence of the

targeted understanding.

6. Our national/state/provincial

tests use primarily multiple-choice

and brief, constructed response

items that do not assess for deep

understanding in the way that you

recommend. How can we prepare

students for these high-stakes standardized tests?

For many educators, instruction and

assessing for understanding are viewed

as incompatible with high-stakes

accountability tests. This perceived

incompatibility is based on a flawed

assumption that the only way to raise test

scores is to cover those things that are

tested and practice the test format. By

implication, there is no time for or need

to engage in in-depth instruction that

focuses on developing and deepening

students’ understanding of big ideas.

Although it is certainly true that we are

obligated to teach to established standards, it does not follow that the best

way to meet those standards is merely to

mimic the format of a standardized test,

and use primarily low-level test items

locally. Such an approach mistakes the

measures for the goals—the equivalent

of practicing for your annual physical

exam to improve your health!

In other words, the format of the test

misleads us. Furthermore, the format

of the test causes many educators to

erroneously believe that the state test or

provincial exam only assesses low-level

knowledge and skill. This, too, is false.

Indeed, the data from released national

tests show conclusively that the students

have the most difficulty with those items

that require understanding and transfer,

not recall or recognition.

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 8

7. Are textbooks important

in the implementation of

UbD framework?

Textual materials can provide important

resources for teachers. However, it is not

a teacher’s job to cover a book page-bypage. A textbook should be viewed as a

guide, not the curriculum. A teacher’s job

is to teach to established standards using

the textbook and other resources in support of student learning.

Major textbook companies have worked

to integrate UbD approaches into their

materials. When well done, such textbooks can be very helpful. Educators

are encouraged to carefully examine

textbooks and use them as a resource for

implementing the curriculum, rather than

as the sole source.

8. Is the UbD framework

appropriate for mathematics?

Some educators have questioned the

use of the UbD framework in mathematics (and other skill-focused areas, such

as world languages or early literacy). The

most commonly expressed concern is

that the UbD framework seems to stress

understanding to the exclusion of basic

knowledge and skills.

The suggestion that UbD framework

does not recognize the need for learners to develop basic knowledge and

skills could not be further from the truth!

Indeed, the UbD Unit Planning Template

in Stage 1 calls for teachers to identify

the important things students should

know (e.g., multiplication tables) and

be able to do (e.g., division). While

acknowledging the importance of the

basics, UbD framework also emphasizes

understanding of conceptually larger

ideas (e.g., equivalence and modeling)

and processes (e.g., problem solving and

mathematical reasoning). This is a point

repeatedly stressed in the new Common

Core Mathematics Standards.

The distinction between basic knowledge and understanding is important not

only for curriculum planning, but also for

pedagogy. Effective educators know from

research that rote learning of mathematical facts and skills does not promote

mathematical reasoning, problem solving, or the capacity to transfer learning.

In fact, test score analysis repeatedly

shows that although learners may be

able to solve a decontextualized problem

that resembles ones that they learned in

a mechanical way, they are often unable

to apply the same facts and skills to a

novel problem or more complex situation. Moreover, superficial learning in a

rote fashion leaves students unable to

explain their reasoning or the meaning of

the concepts involved.

These symptoms point to an essential

goal of UbD framework—teaching so students understand and can transfer

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 9

their mathematics learning to new situations. Because knowledge acquired in

a rote manner rarely transfers, there is a

need to develop understanding of the

larger concepts and processes along with

the basics.

Note: For a good example of an Algebra

1 course designed using the UbD framework, we encourage readers to visit the

following website and click on “Sample

Algebra Course” to download a PDF file.

This example shows how UbD framework

should be applied in mathematics:

www.acps.k12.va.us/curriculum/design.

9. What does it take for a school or

district to successfully implement

the UbD framework?

We propose three general requirements

for successful implementation of the UbD

framework.

1. Help the key constituents (administrators, teachers, parents, students, and the

general public) understand the rationale

for and the requirements of the UbD

framework prior to moving forward.

Without sufficient time to disseminate

basic information and offer necessary

training, key constituents may form opinions based on misconceptions or inaccurately conclude that the UbD framework

is too demanding or irrelevant to their

needs.

2. Teachers must have access to highquality UbD curriculum materials. Weak or

flawed examples convey the wrong idea

of what UbD curriculum should look like,

and teachers who use imperfect resources

will have negative experiences that hurt

the overall reform effort designed to influence student learning. Time is once again

an important factor here; we know from

years of experience that it takes time to

develop high-quality curriculum using the

UbD framework.

3. Long-term and ongoing professional

development is essential to ensure that

all teachers and administrators have sufficient expertise to implement the UbD

framework with fidelity.

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 10

For Further Information

Additional information about the Understanding by Design framework is available

through the following publications.

McTighe, J., & Wiggins, G. (1999). Understanding by Design professional development

workbook. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

http://shop.ascd.org/ProductDetail.aspx?ProductId=411

Tomlinson, C., & McTighe, J. (2006). Integrating differentiated instruction and

Understanding by Design: Connecting content and kids. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

http://shop.ascd.org/productdisplay.cfm?productid=105004

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (expanded 2nd edition).

Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

http://shop.ascd.org/ProductDetailCross.aspx?ProductId=406

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2007). Schooling by design: Mission, action, achievement.

Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

http://shop.ascd.org/ProductDetailCross.aspx?ProductId=822

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2011). The Understanding by Design guide to creating highquality units. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/109107.aspx

Understanding by Design® and UbD™ are trademarks owned by ASCD and may not

be used without written permission from ASCD.

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 11

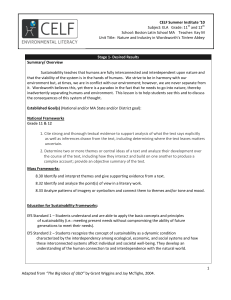

APPENDIX A

UBD IN A NUTSHELL

Stage 1: Desired Results

The Seven Tenets of the UbD Framework

What long-term transfer goals are targeted?

What meanings should students make in order to arrive at

important understandings?

What essential questions will students explore?

What knowledge and skill will students acquire?

What established goals/standards are targeted?

1. Learning is enhanced when teachers think purposefully about curricular planning. The UbD framework

helps this process without offering a rigid process or

prescriptive recipe.

Stage 2: Evidence

What performances and products will reveal evidence of

meaning-making and transfer?

By what criteria will performance be assessed, in light of

Stage 1 desired results?

What additional evidence will be collected for all Stage 1

desired results?

Are the assessments aligned to all Stage 1 elements?

Stage 3: Learning Plan

What activities, experiences, and lessons will lead to

achievement of the desired results and success at the

assessments?

How will the learning plan help students with acquisition,

meaning-making, and transfer?

How will the unit be sequenced and differentiated to optimize

achievement for all learners?

How will progress be monitored?

Are the learning events in Stage 3 aligned with Stage 1 goals

and Stage 2 assessments?

2.The UbD framework helps to focus curriculum and teaching

on the development and deepening of student understanding and transfer of learning (i.e., the ability to effectively

use content knowledge and skill).

3. Understanding is revealed when students autonomously

make sense of and transfer their learning through

authentic performance. Six facets of understanding—the

capacity to explain, interpret, apply, shift perspective,

empathize, and self-assess—can serve as indicators of

understanding.

4. Effective curriculum is planned backward from long-term,

desired results through a three-stage design process

(Desired Results, Evidence, and Learning Plan). This

process helps avoid the common problems of treating the

textbook as the curriculum rather than a resource, and

activity-oriented teaching in which no clear priorities and

purposes are apparent.

5. Teachers are coaches of understanding, not mere purveyors of content knowledge, skill, or activity. They focus

on ensuring that learning happens, not just teaching

(and assuming that what was taught was learned); they

always aim and check for successful meaning making

and transfer by the learner.

6. Regularly reviewing units and curriculum against design

standards enhances curricular quality and effectiveness,

and provides engaging and professional discussions.

7. The UbD framework reflects a continual improvement

approach to student achievement and teacher craft. The

results of our designs—student performance—inform

needed adjustments in curriculum as well as instruction so

that student learning is maximized.

Source: Adapted from Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2011). The Understanding by Design guide to creating high-quality units.

Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 12

APPENDIX B

LEARNING GOALS AND TEACHING ROLES

Learning Goals and Teaching Roles

Three Interrelated

Learning Goals

Note: These three goals are of

course interrelated. However,

there is merit in distinguishing them to sharpen and focus

teaching and assessment.

Teacher Role/

Instructional

Strategies

Note: Like the above

learning goals, these

three teaching roles

(and their associated

methods) work together in pursuit of identified learning results.

ACQUIRE

This goal seeks to help

learners acquire factual

information and basic

skills.

Direct Instruction

In this role, the teacher’s primary role is to inform the learners through explicit instruction

in targeted knowledge and skills;

differentiating as needed.

Strategies include:

❍ diagnostic assessment

❍ lecture

❍ advanced organizers

❍ graphic organizers

❍ questioning (convergent)

❍ demonstration/modeling

❍ process guides

❍ guided practice

❍ feedback, corrections

❍ differentiation

MAKE MEANING

TRANSFER

This goal seeks to help students

construct meaning (i.e., come to an

understanding) of important ideas

and processes.

This goal seeks to support

the learner’s ability to

transfer their learning

autonomously and effectively in new situations.

Facilitative Teaching

Teachers in this role engage the learners in

actively processing information and guide

their inquiry into complex problems, texts,

projects, cases, or simulations; differentiating

as needed.

Strategies include:

❍ diagnostic assessment

❍ using analogies

❍ graphic organizers

❍ questioning (divergent) & probing

❍ concept attainment

❍ inquiry-oriented approaches

❍ Problem-Based Learning

❍ Socratic Seminar

❍ Reciprocal Teaching

❍ formative (on-going) assessments

❍ understanding notebook

❍ feedback/ corrections

❍ rethinking and reflection prompts

❍ differentiated instruction

Coaching

In a coaching role, teachers

establish clear performance

goals, supervise on-going

opportunities to perform

(independent practice) in

increasingly complex situations,

provide models and give ongoing feedback (as personalized

as possible). They also provide

“just in time teaching” (direct

instruction) when needed.

Strategies include:

❍ on-going assessment

❍ providing specific

feedback in the context

of authentic application

❍ conferencing

❍ prompting self assessment and reflection

Source: Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2011). The Understanding by Design guide to creating high-quality

© 2011 Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe

units. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

1703 North Beauregard Street | Alexandria, VA 22311–1714 USA | 1-703-578-9600 or 1-800-933-2723 | WWW.ASCD.ORG

Page 13