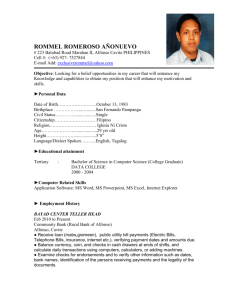

Bacolor - Holy Angel University

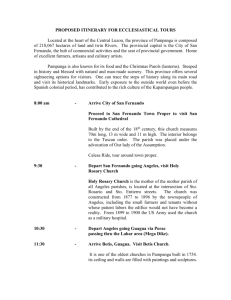

advertisement