Increasing Science Vocabulary Using PowerPoint Flash Cards

advertisement

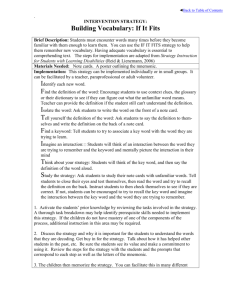

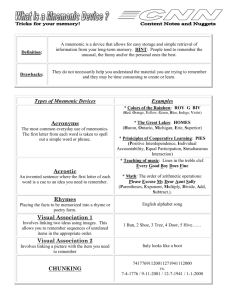

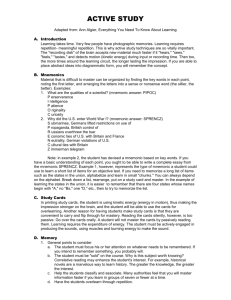

by Sara Aronin and Heather Haynes-Smith A s a group of teachers was eating lunch, the topic of standardized test scores in science came up— students at our school had not done as well as we had hoped. We felt they understood the concepts and concluded a contributing factor was insufficient knowledge of the scientific vocabulary used on the exam. Our school has a large number of students with special needs, as well as students who are learning English as a second language. After further discussion and planning, we decided to address this issue school-wide, integrating science vocabulary into our school culture (see Figure 1 for suggestions for using the strategy described here in a single classroom for a chapter or unit). Exploring science-vocabulary acquisition The vocabulary in science texts poses unique, discipline-specific challenges due to a high prevalence of technical words (Fang 2012). The difficulty in learning these technical words is often a result of the two types of technical vocabulary: (1) technical vocabulary unique to the discipline and not part of students’ everyday language (i.e., mitosis) and (2) technical vocabulary with multiple meanings used in everyday language, but with a different and more specific meaning when used in science texts (i.e., energy). In textbook reading and in hands-on experiments, technical vocabulary words from both categories are difficult to learn (Quinn, Lee, and Valdés 2012). Further, Horn (2003) suggests, “non-White, non-Asian students, as well as students with special needs and English Language Learners, are among the groups most deeply affected by high-stakes testing” (p. 30). Children who are learning English as a second language, as well as those who have reading disabilities, often decode words (using knowledge of letter-sound relationships to correctly pronounce the word) but can’t comprehend the text because they don’t know the word’s meaning. Effective vocabulary instructional practices Vocabulary is acquired both implicitly and explicitly. Implicit vocabulary learning occurs through exposure to oral language as well as exposure to new words through reading (Moats 2004). Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2002) explain that most children need at least 10–12 exposures to a word, in a variety of contexts, before they learn the word. Children who have disabilities in reading or are learning English as a second language require more exposures for implicit learning (Quinn, Lee, and Valdés 2012). Explicit acquisition of vocabulary occurs through direct instruction of new terms. One method for teaching vocabulary to students whose first language is not English or students who have learning disabilities is through the “mnemonic keyword method,” in which students associate images of the vocabulary word with the meaning of the word (Wyra, Lawson, and Hungi 2007). For example, students using the mnemonic keyword strategy in sci- N o v e m b e r 2 0 13 33 Increasing Science Vocabulary Using PowerPoint Flash Cards Figure 1 1. Steps for using the mnemonic keyword strategy in a single classroom Figure 2 Using the mnemonic keyword strategy to learn the word axis Figure 3 Science vocabulary planning chart Before introducing new content, identify keywords that your students are most likely not familiar with. 2. Give a pretest to determine if students know the vocabulary words chosen. 3. Based on the results of the pretest, divide up the vocabulary list among students in the class and have them use the mnemonic keyword strategy (see planning chart, Figure 3) to create slides for their assigned words. 4. Have students turn in their slides and check to make sure they have accurately defined their words, that the picture is suitable for most learners, and that they’ve used correct grammar; students who did not achieve mastery should resubmit their slides. 5. Assemble all of the slides into one slide show that you then show to the class during passing periods and downtime and send home with students to practice. 6. Throughout the chapter or unit, continually do formative assessment to see if students are learning and understanding the vocabulary. When an identified word comes up in class, make sure to go over the definition. ence to learn that the word axis means an imaginary line on which an object rotates (Earth’s axis) would first come up with a mnemonic that reminds them of the word—John says he thinks of an ax when he thinks of the word axis. Next, students incorporate the image with the definition—Earth with its axis drawn by an ax (see Figure 2). The mnemonic keyword method is a successful tool for teaching vocabulary words (Wyra, Lawson, and Hungi 2007), as so many science vocabulary words are unfamiliar and seldom used in students’ daily language (Shanahan 2012). When students are required to create associations between new terms and words with known vocabulary and images, they are applying multiple linguistic levels of the brain, thereby enhancing the number of exposures to the new word. With the mnemonic keyword method, students mentally create an image with the word and the meaning of the word. 34 Science vocabulary word ____________________ Grade ____ Definition _________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Is this word specific to science? q Yes q No Does this word have multiple meanings but with a more specialized meaning in science? q Yes q No Step 1: Type word on slide. Step 2: Choose an image using the mnemonic keyword method and insert it here. Apply animation so the word arrives before the image (this assists in recalling the definition). Step 3: Insert another transition to the same slide and with the appropriate definition. After the images are constructed, students build an association between the images, activating multiple levels of cognition. Although the individual imaging of the words is influential, students are able to take a peer’s imaging and make it their own better than with traditional forms of learning vocabulary. Implementing PowerPoint flash cards Based upon the above research on effective instructional strategies, the relationship between vocabulary and reading comprehension, and the effect of imagery Increasing Science Vocabulary Using PowerPoint Flash Cards in supporting vocabulary recall, we developed a schoolwide plan to use student-created digital flash cards created in PowerPoint and incorporating many elements of the software, including font color, font size, animation, slide transition, and importing/creating images (any presentation software that is able to do similar functions will also work). Our team decided that every vocabulary word from a state-issued vocabulary list for Florida’s science standardized test would have one slide with three elements utilizing transitions. First, the word is presented on the slide. Next, an image that uses the mnemonic keyword method to associate with the word and definition is placed on the slide, applying animation so the word arrives before the image. The image’s function is to assist in the recall of the definition. Finally, there is another transition to the same slide and the definition appears. Figure 3 is a planning document that can be used by students or teachers to create slides, and Figure 4 shows the three stages of the PowerPoint slide for the word carnivore (a student who said the word carnivore reminded her of the carnival chose a picture of a lion with a man’s head in its mouth to represent both the carnival and that “the lion eating a man is a carnivore”). Figure 5 is a PowerPoint slide for the word vibration. Integrating science vocabulary as a schoolwide, universal support We divided up the state-issued vocabulary lists for sixth-, seventh-, and eighth-grade science words among seventh- and eighth-grade students. Each student then created approximately three vocabularyword slides using the mnemonic keyword method. We had students make these slides in a computer lab while in science class during the first month of class. The seventh graders did the sixth-grade words as a review, the eighth graders did the seventh-grade words as a review, and the honors class worked closely with the teacher to complete the eighth-grade words. Each student could choose the colors, animation, and picture used for the assigned vocabulary words. Students were also instructed to think about images that represented the definition not only to themselves, but that would also assist others in remembering the definition of the term. In other words, students were explicitly told not to make the pictures something only the creator would understand. Only minimal accommodations, which were already in place (such as a rollerball mouse and enlarged keyboard), were needed for students with disabilities to complete the assigned vocabulary-word slides due to the built-in supports of PowerPoint. Figure 4 PowerPoint flash-card slide for carnivore Individual students’ PowerPoints were turned in to the student’s science teacher, who checked them for accuracy and assigned a grade. Students were responsible for fixing and resubmitting slides that the teacher identified as having inaccurate information, a picture that would not be understood by most students, or a sentence that was not grammatically correct. Students needed to achieve mastery on the slides in order to receive credit for the assignment, even if that took several sets of revisions. These student-generated slides were then assembled by the science teachers into several PowerPoints of 25 to 30 words each with the words in random order from all three grade-level lists. One of the PowerPoints was run on the schools’ televisions before morning announcements and during passing periods, and on a large screen during lunch. If your school does not have such systems, they could be run off of individual teachers’ computers in individual classrooms during these same time frames, since the slide shows are set to run on automatic with the slides changing after 10 seconds per slide. Students were excited to identify the slides that they had made and look for those of friends. In order for the words to show up with some frequency, sets of words (25–30) were chosen to run for a week at a time. For some students, the words were a review. For other students, these slide shows were the first time they were exposed to the words. This system allowed students to have multiple exposures to and reviews of the science vocabulary words. In the month prior to the state test, we used a different set of words each day (they had all been shown previously for a week at a time). We found this to be ex- N o v e m b e r 2 0 13 35 Increasing Science Vocabulary Using PowerPoint Flash Cards Figure 5 PowerPoint flash-card slide for vibration Other ideas Although we did not do it, utilizing interactive whiteboards with the PowerPoint slides could add other kinesthetic and audio/visual components to learning the vocabulary. Having the weekly words on a word wall, whether in individual classrooms or in a prominent place in the school, would also allow for additional exposure to the words. One final idea is to have the week’s science vocabulary words in an online flashcard program such as StudyStack, with a link on the school’s website. n References tremely helpful with reviewing terms that were used in sixth- and seventh-grade science classes in preparation for the standardized test at the end of eighth grade that covers the entire middle school science curriculum. We also found that students in all grades were familiar with more vocabulary terms prior to instruction as a result of being introduced to the words on the slides, even though they had not yet been taught the material. Individual teachers could use this strategy to review words from past units or years, with students in the class working together to create the final PowerPoint presentation (see Figure 1 for instructions on using the mnemonic keyword method to teach new vocabulary in a single classroom). The PowerPoint presentation was also used as a game. Our vice principal would go to the cafeteria to ask vocabulary questions of students in line to buy lunch. He would pick words from previous weeks’ slides to add an additional layer of review as well as to check for understanding of the words. Students who answered correctly were allowed to advance to the front of the lunch line. An unexpected outcome was that students became very competitive trying to say the definition before the transition showing it came on the screen, demonstrating that students were in fact learning from the slides. The principal supported the initiative during walkthroughs, trying to “catch” teachers (not just science teachers) and staff using the week’s vocabulary and would reward them with gift certificates provided by the PTA. Everyone in the school used the vocabulary, including the cafeteria workers, who talked about conduction and convection taking place in the kitchen! 36 Beck, I.L., M.G. McKeown, and L. Kucan. 2002. Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford. Fang, Z. 2012. The challenges of reading disciplinary texts. In Adolescent literacy in the academic disciplines: General principles and practical strategies, eds. T.L. Jetton and C. Shanahan, 34–68. New York: Guilford. Horn, C. 2003. High-stakes testing and students: Stopping or perpetuating a cycle of failure? Theory Into Practice 42 (1): 30–41. Moats, L.C. 2004. Language essentials for teachers of reading and spelling (LETRS): Module 4, The mighty word: Building vocabulary and oral language. Longmont, CO: Sopris West Educational Services. Quinn, H., O. Lee, and G. Valdés. 2012. Language demands and opportunities in relation to Next generation science standards for English language learners: What teachers need to know. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, Understanding Language Initiative at Stanford University. Shanahan, C. 2012. Learning with text in science. In Adolescent literacy in the academic disciplines: General principles and practical strategies, eds. T.L. Jetton and C. Shanahan 154–171. New York: Guilford. Wyra, M., M.J. Lawson, and N. Hungi. 2007. The mnemonic keyword method: The effects of bidirectional retrieval training and of ability to image on foreign language vocabulary recall. Learning and Instruction 17 (3): 360–71. Sara Aronin (sara.aronin@mail.wvu.edu) is an assistant professor in the Department of Special Education at West Virginia University in Morgantown, West Virginia. Heather Haynes-Smith is an assistant professor in the Department of Teacher Education at Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas.