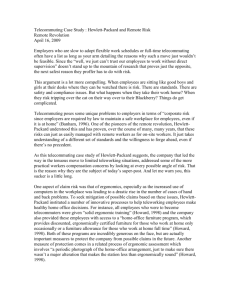

occasional telecommuting - Center for WorkLife Law

advertisement