Telecommuting Case Study - Hewlett

advertisement

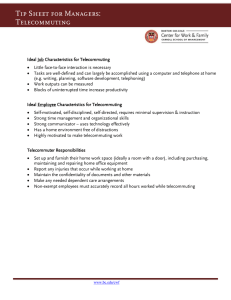

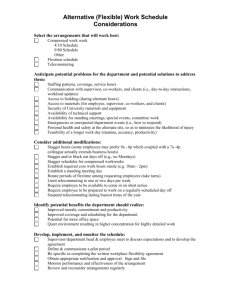

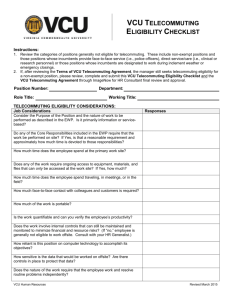

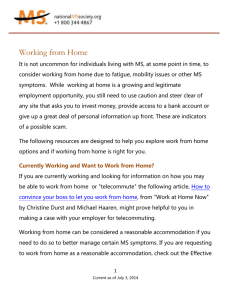

Telecommuting Case Study : Hewlett-Packard and Remote Risk Remote Revolution April 16, 2009 Employers who are slow to adopt flexible work schedules or full-time telecommuting often have a list as long as your arm detailing the reasons why such a move just wouldn’t be feasible. Since the “well, we just can’t trust our employees to work without direct supervision” doesn’t stand up to the mountain of research that proves just the opposite, the next safest reason they proffer has to do with risk. This argument is a lot more compelling. When employees are sitting like good boys and girls at their desks where they can be watched there is risk. There are standards. There are safety and compliance issues. But what happens when they take their work home? When they risk tripping over the cat on their way over to their Blackberry? Things do get complicated. Telecommuting poses some unique problems to employers in terms of “corporate risk since employers are required by law to maintain a safe workplace for employees, even if it is at home” (Banham, 1996). One of the pioneers of the remote revolution, HewlettPackard understood this and has proven, over the course of many, many years, that these risks can just as easily managed with remote workers as for on-site workers. It just takes understanding of a different set of standards and the willingness to forge ahead, even if there’s no precedent. As this telecommuting case study of Hewlett-Packard suggests, the company that led the way in the tenuous move to limited teleworking situations, addressed some of the more practical workers compensation concerns by looking at every possible angle of risk. That is the reason why they are the subject of today’s super-post. And let me warn you, this sucker is a little long. One aspect of claim risk was that of ergonomics, especially as the increased use of computers in the workplace was leading to a drastic rise in the number of cases of hand and back problems. To seek mitigation of possible claims based on these issues, HewlettPackard instituted a number of innovative processes to help teleworking employees make healthy home office decisions. For instance, all employees who were to become telecommuters were given “solid ergonomic training” (Howard, 1998) and the company also provided these employees with access to a “home-office furniture program, which provides discounted, ergonomically certified furniture for those who work at home only occasionally or a furniture allowance for those who work at home full time” (Howard, 1998). Both of these programs are incredibly generous on the face, but are actually important measures to protect the company from possible claims in the future. Another measure of protection comes in a related process of ergonomic assessment which involves “a periodic photograph of the home-office arrangement, just to make sure there wasn’t a major alteration that makes the station less than ergonomically sound” (Howard, 1998). During the experimental period of the Hewlett-Packard telecommuting trial, company officials and human resources managers examined the possibility of risk from all levels and implemented a written agreement that all employees who were part of the initial teleworking experiment were required to sign. During these initial experiments in the early 1990s, Hewlett-Packard was able to refine their telecommuting agreement to manage the host of complex issues inherent to the employee being at home during the day--outside of a carefully managed and monitored situation. One of the most critical issues that emerged involved general matters of time management and tracking and how to assist and record the amount of time worked without traditional measurements. To remedy the problem of not knowing how employees were managing their time, the company created specific elements in their telework agreement that instituted flexible policies that were of benefit to both the telecommuter and the organization. Important elements of these agreements included, for example, measures for keeping track of an assigned number of hours the employee was to be working and what those hours were on a daily basis. The company made it clear to employees that they were not locked into a rigid 9 to 5 schedule, however an important component of the agreement was that the employee did need to set an exact schedule and follow through by working those hours at the same pace he or she might do if committed to the office (Howard, 1998). The time and tracking component of the Hewlett-Packards telecommuter agreement is noteworthy because it directly addresses two of the most prominent concerns for employers and employees alike—time and progress as well as circumstantial scheduling potential. On the one hand, it grants employers some control over the nature of the workday and allows for firm expectations to be set based on the stated schedule. The benefits for the employee are in the area that is stated as being most important when employees crave a teleworking situation—flexibility. In this model, the crucial aspect of flexibility is retained for the employee while still allowing the employer some degree of control over the time spent working. With such an arrangement, a telecommuting parent could decide to take his child into a daycare center at 9:30, run errands and have breakfast and do some general housework until 11:00 a.m. and then begin working at 11:30. In the agreement the employee makes with the company, he begins at the firmlyenforced time of 11:30 and works until he needs his wife arrives home after picking up their child at 7:30. This is certainly not an ideal schedule for everyone, but given the employee’s home situation (perhaps his wife works until 7:00) the flexibility makes life far less stressful and more tailored to the unique circumstances of his family. The issue of telecommuting workers with families, however, comes with its own set of concerns for employers who are often worried about how the balance might be struck if the children are present during the time work is to be completed. One of the major provisions in the agreement Hewlett-Packard formed was that teleworkers could not expect the new situation of being at home to mean that they could pull children out of childcare situations and keep them at home in an effort to balance the two duties. According to an assessment of the company’s stance, “telecommuting is not supposed to be a substitute for dependent-care arrangements” (Howard, 1998). To remedy this possible cause for concern, Jerry Cashman, who served as Hewlett-Packard’s work and personal life manager during the experimental phase (and following the shift to an even larger number of telecommuting employees) and the team handling the agreement looked for policy solutions to help guide employees. Cashman stated that “a telecommuter can work within the parameters if dependent care if provided inside the home when the employee is working and the office is separated from the home-care situation” (from interview Howard, 1998) and furthermore, that a home office would have to be an area that was, in every respect, like the traditional office with quiet and organized areas and not being used as a dual child-watching and working station. In other words, by inserting this into the agreement, Hewlett-Packard was suggesting that teleworkers could enjoy time with their families, but this had to be in an area outside of the home office and outside of the hours set aside for work. I should refresh here and mention that this is before widespread internet use with sophisticated employee and monitoring tools. Risk management for telecommuters is a matter of sense and understanding of what needs to be done but once employers get past the initial hurdle of figuring out these standards, it should be cake, no?