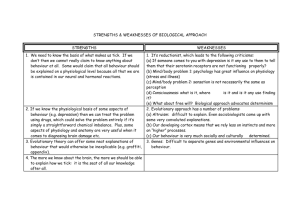

two example case reports

advertisement