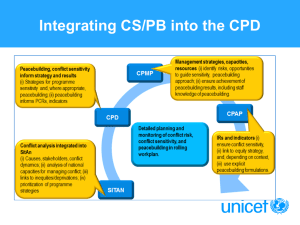

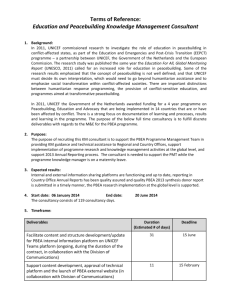

report - Disasters and Conflicts

advertisement