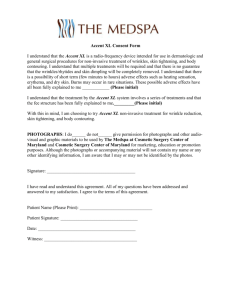

Accentual type vedo proofs

advertisement