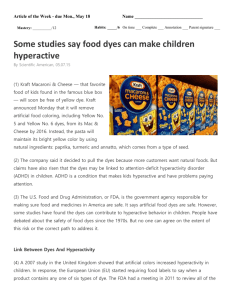

Petition to Ban the Use of Yellow 5 and Other Food Dyes

advertisement