Pituitary Gland Tumours

advertisement

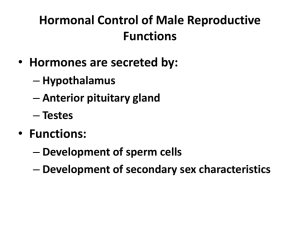

Pituitary gland tumours Pituitary gland tumours are classed as brain tumours. However they are different to most other brain tumours and are usually benign (non-cancerous). On this page The pituitary gland Pituitary tumours Causes of a pituitary gland tumour Signs and symptoms Tests and investigations Treatment Your feelings Useful organisation References and thanks This information should be read with our general information about brain tumours. We hope this information answers your questions. If you have any further questions, you can ask your doctor or nurse at the hospital where you are having treatment. The pituitary gland The pituitary gland is a small, oval-shaped gland found at the base of the brain (see diagram below), below the optic nerve (the nerve that leads to and from the eye). The pituitary gland produces hormones, which control and regulate the other glands in the body. These glands release hormones that help control and regulate growth and how the body works. The pituitary gland is divided into two parts: the anterior (front) and posterior (back). The anterior pituitary produces six hormones: growth hormone, which controls growth prolactin, which stimulates the production of breast milk after childbirth ACTH (adrenocorticotrophic hormone), which stimulates the production of hormones from the adrenal glands TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone), which stimulates the production of hormones from the thyroid gland FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone) and LH (leuteinising hormone), which stimulate the ovaries in women and the testes in men. The posterior pituitary produces: ADH (anti-diuretic hormone), which reduces the amount of urine produced by the kidneys oxytocin, which stimulates the contraction of the womb during childbirth and the release of breast milk for breastfeeding. Page 1 of 6 - Pituitary gland tumours - Macmillan 2014 pdfcrowd.com Side view of the head Pituitary tumours Cells within the brain normally grow in an orderly and controlled way. But if for some reason this order is disrupted, the cells continue to divide and form a lump or tumour. A tumour can be either benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Although a benign tumour can continue to grow, the cells do not spread from the original site. In a malignant tumour, the cells can invade and destroy surrounding tissue and may spread to other parts of the brain. Almost all tumours of the pituitary gland are non-cancerous and do not spread. They are sometimes called adenomas. Pituitary tumours are either secreting (producing hormones) or non-secreting tumours (not producing hormones). Secreting tumours can release excess amounts of any of the pituitary hormones, and are named after the hormone that’s being overproduced, for example a prolactin-secreting tumour. About 4,700 people are diagnosed with brain tumours each year in the UK. About 1 in 10 (10%) of these tumours are in the pituitary gland. They are most commonly found in young or middle-aged adults. Causes of a pituitary gland tumour As with most brain tumours, the cause of pituitary tumours is unknown. Research is being carried out into possible causes. Signs and symptoms Signs and symptoms of pituitary tumours are caused either by direct pressure from the tumour itself or by a change in the normal hormone levels. As the tumour grows, it puts pressure on the optic nerve (which leads to the eye) and this often causes headaches and sight problems. Symptoms caused by a change in hormone levels usually take a long time to develop. Prolactin-secreting tumours These are the most common type of secreting tumour. Women with this type of tumour may notice that their monthly periods stop and they may also produce small amounts of breast milk. Symptoms in men may Page 2 of 6 - Pituitary gland tumours - Macmillan 2014 pdfcrowd.com include impotence (inability to have an erection). Infertility (inability to have children) is common in both men and women, and the tumour may be discovered during routine tests for infertility. Symptoms of other secreting tumours will relate to the hormones that are released. Growth hormone-secreting tumours Excess production of growth hormones can cause a condition called acromegaly. This leads to abnormal growth and causes enlargement of the hands, feet, lower jaw and brows. It can also lead to high blood pressure, diabetes and excess sweating. TSH-secreting tumours A tumour that releases too much TSH may cause symptoms like weight loss, palpitations and feeling shaky and anxious. These tumours are extremely rare. ACTH-secreting tumours Overproduction of ACTH can produce a number of symptoms including Cushing’s syndrome, which is characterised by a round face (known as moon face), weight gain, increased facial hair in women and mental changes such as depression. Other anterior pituitary tumours Tumours that secrete FSH or LH are very rare and are likely to cause infertility. Posterior pituitary tumours Tumours in the posterior pituitary are very rare and disturbances in this area are more likely to be caused by pressure being applied to the area from the surrounding tissues. The most common symptom of a problem in the posterior pituitary is a condition called diabetes insipidus, which is different from the more common diabetes mellitus. The main symptom of diabetes insipidus is being very thirsty and passing large amounts of very weak urine. Tests and investigations For your doctors to plan your treatment, they need to find out as much as possible about the type, position and size of the tumour, so you may have a number of tests and investigations. Eye tests By examining your eyes, your doctor can detect pressure on the optic nerve, which may indicate that a tumour is present. A simple test may also be done to check your visual fields (range of vision). Pituitary tumours are often discovered during a blood test. If high levels of pituitary hormones are found in your blood, your doctor may arrange for you to have a CT scan or MRI scan. The scans will normally be able to confirm whether a pituitary tumour is present or not. CT (computerised tomography) scan A CT scan takes a series of x-rays that build up a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the body. The scan is painless and takes 10-30 minutes. CT scans use small amounts of radiation, which will be very unlikely to harm you or anyone you come into contact with. You will be given an injection of a dye, which allows particular areas to be seen more clearly. This may make you feel hot all over for a few minutes. If you are allergic to iodine or have asthma you could have a more serious reaction to the injection, so it’s important to let your doctor know beforehand. Watch our video about having a CT scan at macmillan.org.uk/testsandscans MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan Page 3 of 6 - Pituitary gland tumours - Macmillan 2014 pdfcrowd.com This test is similar to a CT scan but uses magnetism instead of x-rays to build up a detailed picture of areas of your body. Before the scan you may be asked to complete and sign a checklist. This is to make sure it’s safe for you to have an MRI scan. Before having the scan, you’ll be asked to remove any metal belongings including jewellery. Some people are given an injection of dye into a vein in the arm. This is called a contrast medium and can help the images from the scan show up more clearly. During the test you will be asked to lie very still on a couch inside a long cylinder (tube) for about 30 minutes. It is painless but can be slightly uncomfortable, and some people feel a bit claustrophobic during the scan. It’s also noisy but you’ll be given earplugs or headphones. Treatment Your treatment will usually be planned by a team of specialists known as a multidisciplinary team (MDT). The team will usually include: a doctor who specialises in disorders of hormone production (endocrinologist) a doctor who operates on the brain (neurosurgeon) a doctor who specialises in treating illnesses of the brain (neurologist) a doctor who specialises in treating brain tumours (an oncologist) a specialist nurse and possibly other healthcare professionals, such as a physiotherapist or dietitian. Consent Before you have any treatment, your doctor will give you full information about its aims and what it involves. They will ask you to sign a form saying that you give your permission (consent) for the hospital staff to give you the treatment. No medical treatment can be given without your consent. Benefits and disadvantages of treatment Treatment can be given for different reasons and the potential benefits will vary for each person. If you have been offered treatment that aims to cure your tumour, deciding whether to have the treatment may not be difficult. However, if a cure is not possible and the treatment is to control the tumour for a period of time, it may be more difficult to decide whether to go ahead. If you feel that you can’t make a decision about the treatment when it is first explained to you, you can always ask for more time to decide. You are free to choose not to have the treatment and the staff can explain what may happen if you do not have it. You don’t have to give a reason for not wanting to have treatment, but it can be helpful to let the staff know your concerns so they can give you the best advice. Surgery Surgery is the most common treatment for most pituitary tumours. The aim of surgery is to remove the tumour and to leave at least some of the normal pituitary gland behind. This is not always possible, and in some cases the whole gland may need to be removed. The procedure is called endoscopic transphenoidal resection and involves the surgeon passing a thin tube up the nose to reach the pituitary gland. There is a camera at the end of the tube so the surgeon can see the area that needs to be removed. Because there is no need to open the skull to carry out the operation, recovery after surgery is much quicker than other operations for brain tumours. Your doctor will explain the operation to you in more detail beforehand. Drug treatment Some prolactin-secreting tumours can be treated with a drug treatment that reduces the production of prolactin. These drugs include bromocriptin and cabergoline. If the whole pituitary gland is removed, drugs will have to be taken to replace the hormones that are normally produced (hormone replacement). Page 4 of 6 - Pituitary gland tumours - Macmillan 2014 pdfcrowd.com Radiotherapy Radiotherapy treatment uses high-energy rays to destroy abnormal cells, and is an extremely effective and safe form of treatment. It's often used following surgery for all types of pituitary tumour. Some small tumours which are away from the optic nerves may be suitable for radiosurgery. Radiosurgery is a type of stereotactic radiotherapy. It aims radiotherapy beams directly at the brain tumour from different angles around your head. Radiosurgery is usually given in a single dose, but you may have more if necessary. Follow-up Treatment of pituitary tumours is usually very successful, although many people will have to continue taking hormone replacements, sometimes for the rest of their lives. Regular check-ups at an endocrinology clinic are likely and may continue for several years. You may have further scans performed and will have blood tests to monitor your hormone levels. Your feelings You may find the idea of a tumour affecting your brain extremely frightening. The brain controls the body and not being in control is something that can be very worrying. You may experience many different emotions, including anxiety and fear. These are all normal reactions and are part of the process many people go through in trying to come to terms with their condition. Many people find it helpful to talk things over with their doctor or nurse, or with one of our cancer support specialists. Family members and close friends can also offer support. We have more information about dealing with the emotional effects of cancer and talking about your cancer. Useful organisation The Pituitary Foundation The Pituitary Foundation is a national organisation that provides information and support for people with pituitary disorders, and their relatives, friends and carers. References and thanks This information has been compiled using information from a number of reliable sources, including: Snyder et al, Causes, presentation and evaluation of sellar masses, January 2014, www.uptodate.com (accessed May 2014) NICE Guidance. Improving outcomes for people with brain and other CNS tumours – The manual. 2006. De Vita, et al. Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 8th edition. 2008. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Greenman Y, Stern N. Non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2009. 23: 625–638. Souhami, Hochhaser. Cancer and its management. 6th edition. 2010. Wiley-Blackwell. Tonn, et al. Neuro-oncology of CNS tumours. 2006. Springer. With thanks to Dr Carmel Loughrey, Consultant Neuro-Oncologist, who reviewed this edition. Page 5 of 6 - Pituitary gland tumours - Macmillan 2014 pdfcrowd.com Thanks to people like you Thank you to all of the people affected by cancer who reviewed what you're reading and have helped our information to grow. You could help us too when you join our Cancer Voices Network - find out more. Content last reviewed: 1 May 2014 Next planned review: 2016 We make every effort to ensure that the information we provide is accurate and up-to-date but it should not be relied upon as a substitute for specialist professional advice tailored to your situation. So far as is permitted by law, Macmillan does not accept liability in relation to the use of any information contained in this publication or third party information or websites included or referred to in it. Macmillan Cancer Support, registered charity in England and Wales (261017), Scotland (SC039907) and the Isle of Man (604). A company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales company number 2400969. Isle of Man company number 4694F. Registered office: 89 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7UQ. For cancer support every step of the way, call Macmillan free on 0808 808 00 00 (Mon-Fri, 9am-8pm) or visit macmillan.org.uk Page 6 of 6 - Pituitary gland tumours - Macmillan 2014 pdfcrowd.com