Getting to Yes for Your Library

advertisement

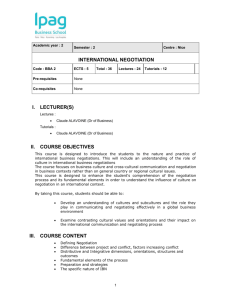

AALLApr2011:1 3/16/11 1:11 PM Page 9 Getting to Yes for Your Library Negotiating vendor contracts in your favor By Jane Baugh W e are all negotiators. From the toddler who wants a cookie, to the driver glaring at a competitor across the aisle for “his” parking space, to librarians renewing a vendor contract, people rely on innate and learned skills to get what they want. The techniques and the stakes vary, but at the end of the negotiation we all want to achieve success. Nonetheless, the very idea of formal negotiation causes stress in many people. Many are conflict-averse in temperament, and others don’t have enough experience with the process to be comfortable with it. Preparation and familiarity with both the theory and the technique of negotiating can make the process less stressful—and more successful. In Three Steps to Yes: The Gentle Art of Getting Your Way (Three Rivers Press, 2002), Gene Bedell defines negotiation as “back-and-forth communication designed to reach an agreement when you and the other side have some interests that are shared and others that are opposed.” Toddlers want cookies, while mothers want healthy children; both want the child to be happy. Both drivers want to park in the same spot close to the mall—this is both the shared and the opposing interest. In the case of librarians and vendors, both want the library’s end users to be able to have the best information available to meet their needs, whether those needs be papers that earn good grades or briefs that win cases; the differences generally involve which (or how much) information is available to the library and for how much money. Law librarians, by virtue of our training and experience, are well qualified to participate in negotiations with information vendors. We know what our end users want and need to get their jobs done, and we use those same tools to assist those users. Librarians deal with a wide variety of people and personalities in the course of a business day, and a skilled reference interviewer can often determine whether the other side has information that it has not yet shared. As trained researchers, librarians can gather background information needed for the negotiation and can organize it in a way that will keep the negotiations moving and focused on the task at hand. Primary Types of Negotiation There are two main schools of thought regarding negotiation skills. The Harvard Business School and its Negotiation Project advocate what they call principled negotiation, which assumes that all sides want to collaborate to a certain degree and that everyone is working for a win/win result. In many negotiation situations, however, especially those involving money, neither side is particularly interested in collaborating, and the negotiator who is looking for a good outcome needs to be prepared for those situations to arise. © 2011 Jane Baugh • image © iStockphoto.com/Alexey Belotsvetov Principled Negotiation In 1981, Roger Fisher and William Ury of the Harvard Negotiation Project published Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement without Giving In (Penguin, 1981), which advances the technique of principled negotiation. Its four key elements are: separating the people from the problem; focusing on the parties’ interests, not their bargaining positions; discussing a variety of options before making a final decision; and arriving at an end result that can be based on an objective standard. There are several key points to consider. People: Many of us have longstanding relationships with our vendor representatives who may come for training on a regular schedule and will continue to come after the negotiations are over (provided the negotiations are successful). You will still have to work with them so it is helpful to understand their points of view—even if you don’t agree with them—and to be respectful of them and of the vendor’s negotiators. Interests: Focus on the parties’ shared interest. The vendor wants to gain or keep your business, and you want to end up with a contract that will give your attorneys the information they need without bankrupting the firm. Don’t dig yourself so far into a position that you can’t dig out without saving face. If your organization has any deal-breaking clauses, like requests that your firm appear in advertisements for their products, let the vendor know that those AALL Spectrum ■ April 2011 9 AALLApr2011:1 3/16/11 11:42 AM Page 10 Checking Out the Contract: Contract Best Practices Compiled by Clare D’Agostino and Connie Smith After finalizing the negotiations, it is important to confirm that the correct information is in the formal agreement. Do not assume anything. Start with the basics. Are the following items stated correctly? Organization name and type (nonprofit, LLP, etc.) Mailing address and contact person (Your office may have relocated or your contact person may have changed since the previous renewal.) Locations-Does this contract cover one location or multiple ones, and are all of them listed properly? Does the agreement cover the addition or removal of locations during the life of the contract? Effective dates-Very often a template or older version is used to create the document, and old dates sometimes carry over. Check for vendor contract designations-Did last year’s contract say “Enterprise” but this year’s contract says “National”? Did last year’s contract have a number designation different from this year’s? These changes can be an indicator of subtle differences that may not have been spelled out in the negotiations. Ask the vendor to use the previously accepted contract or redline the differences. Confirm that money amounts and payment terms match your previously agreed-upon terms. When the invoice arrives, check again. Read the definitions carefully-Some electronic resource contracts state that the product can be used by the firm’s employees, and a partner is not an employee. If the contract covers multiple products, make sure you understand the acronyms, abbreviations, or file names, so that you can ensure that you are getting the correct resources. 10 AALL Spectrum ■ April 2011 are off the table immediately or there is no contract. Options: Discuss a number of possibilities before coming to a final decision. These could include which databases are included, the method for calculating charges, or whether the contract is for a site license or for a set number of users. Invent options for mutual gain (see Getting to Yes, page 11), but don’t give in to pressure and end up with a contract that doesn’t serve your needs. Objective standard: Insist that the end result be based on an objective, quantifiable standard. “This is our best offer and it’s a good one” is not objective—a contract based on usage figures or customary charges is. The “EASY” Process In The One-Minute Negotiator (BerrettKoehler Publishers, Inc., 2010) authors Don Hutson and George Lucas recognize that not everyone wants to collaborate and that every negotiation differs according to its participants. They encourage the use of the “EASY” process: Engage: Recognize you are in a negotiation and review viable strategies Assess: Evaluate your tendency, and that of the other side, to use various negotiation strategies Strategize: Select the strategy that fits the negotiation you are in Your One-Minute Drill: Take a minute to review these steps each time you begin a negotiation Hutson and Lucas have identified four negotiation strategies—competition, collaboration, avoidance, and accommodation. It is helpful for the negotiator to know not only what his/her strategy is but to also be able to identify the strategy of the person on the other side of the table. If you assume an accommodating style, which is the natural style of many librarians, while your vendor is clearly in competitive mode, you are not likely to get what you want. Furthermore, the vendor will remember that accommodation the next time your contract is due to be renewed and will take advantage of it. Collaboration would be the ideal, but true collaboration is rare, especially when both sides are looking at their bottom lines. Preparation is Key Before entering into a negotiation process, make sure you prepare. The more information you have at your disposal, the higher your likelihood of success. For new contracts, research the product, using both the manufacturer’s information releases about it and the experiences of your colleagues. For contract renewals, note your experiences with the product, its customer service personnel, and the content included in your agreement, and have a good grasp of your library’s previous usage patterns. This is especially true for flat rate contracts as the new offer will be based on those previous usage patterns. Prepare also for the personal aspects of the negotiation. If you know the negotiator, you will have a good idea of what his/her personal negotiating style will be. If you will be conducting the discussions with an unknown quantity, be prepared to make a judgment about that person’s style very early in the process; if you determine you are wrong after beginning talks, adjust your style and tactics accordingly. Noticing whether the other side focuses on his or her relationship with others at the table or on the task at hand is a good way to judge what his or her negotiation style is likely to be. “Knowing in advance what your ‘must have’ terms are as well as your ‘nice to have’ terms and where you have flexibility on these terms will also help you engage in an informed negotiation,” says Scott Schwartz, a shareholder at Cozen O’Connor in Philadelphia who reviews and negotiates most of the firm’s information-related agreements. The Negotiation Process It is best not to assume that you and the vendor are starting on the same page in the negotiation process. Vendors assume we’ll balk at their pricing and so may come in with an exaggerated price in order to get what they want while appearing to make concessions for the library. Others may come in with just the price levels you were hoping for but have cut back on the amount of content included for that price, forcing you to argue for more material to be included in the contract. Since you want the most content you can get for the lowest possible price, keep both of these factors in mind during negotiations. Be focused on and aware of what is going on around you during the negotiations. Have you noticed a change in the other side’s demeanor or tactics? Take notes about what’s being said and refer to them, especially if someone describes a change or concession that is not the way you remember it. Make it your business to keep everyone on the same page with the same idea about what’s been said. If you don’t get anywhere with the person you are dealing with, ask to meet with that person’s manager or someone else at the company. If you absolutely cannot arrive at a result that is satisfactory for your firm or institution, break off the negotiations, either for that day or completely. AALLApr2011:1 3/16/11 11:42 AM Page 11 After the Negotiation Phase Between the negotiations and the actual signing of the contract, it is a good idea for the people representing your library in the process to meet and discuss the negotiation session. Review the notes you took and add to them during the negotiating team’s post-mortem. Determine how close you got to your goals during the negotiations and review the points or principles gained and lost during the discussions. If you agreed to follow up on any points raised during the negotiations, do it now. Arriving at Win/Win for All Parties At this point, you’re ready to notify the vendor that you will either accept or decline the offer as it stands. If you are accepting, it’s time to sign. If you are declining, the vendor will likely make a counter-offer; if the counter is closer to your goals than the previous offer, you may choose to accept it now. Remember, however, that walking away is always an option if you do not think any of the vendor’s offers will be advantageous for your firm. “Thinking creatively can also assist in reaching a resolution to an otherwise untenable negotiation,” suggests Schwartz. “I have seen many negotiations that were otherwise at a standstill that concluded successfully based on thinking outside of the proverbial box.” The toddler may not get her cookie, but apple slices are a sweet substitute. Your firm gets the databases it wants at the price level it wants, and the vendor keeps your business. The parking lot negotiation, however, may not end well—unless another space opens up that’s even closer to the stores. ■ Jane Baugh (baugh@woodsrogers. com) is the director of information services at Woods Rogers PLC in Roanoke, Virginia. announcements It’s Time to Renew Your AALL Membership Renew early for a chance to win a free 2011 AALL Annual Meeting registration In March, AALL dues invoices for 2011-2012 were mailed to all library directors for their institutionally paid memberships and to all other individual members. The deadline for membership renewal is May 31. This year, when you renew early—by May 1—you will be entered in a drawing for a free 2011 AALL Annual Meeting and Conference registration. If you renew on time—by May 31—you’ll be entered in a drawing for a free AALL webinar of your choice in 2011-2012. Following is the 2011 membership renewal schedule: March: First dues invoices mailed out. May: Second dues invoices mailed out. June: Third dues invoices mailed out. July: Expiration notices e-mailed to all members— individuals and those paid by institutions. August 1: Expired members deleted from the AALL membership database, and access to the AALLNET Members Only Section and Law Library Journal and AALL Spectrum subscriptions discontinued. For more information or to renew your membership online, view the application form on AALLNET at www.aallnet.org/about/join.asp. If you have any questions about your membership renewal, contact AALL Headquarters at membership@aall.org or 312/205-8022. Join Us in Philly! The program “Getting to Yes for Your Library: Negotiating Vendor Contracts in Your Favor,” sponsored by the Private Law Libraries Special Interest Section and the Committee on Relations with Information Vendors, will be presented at the 2011 AALL Annual Meeting in Philadelphia on Tuesday, July 26, at 9 a.m. Speakers will be Clare D’Agostino, assistant counsel to the firm, and Connie Smith, director of firm libraries, both at Morgan, Lewis & Bockius in Philadelphia, as well as Scott Schwartz, shareholder, and Loretta Orndorff, director of library services, both at Cozen O’Connor in Philadelphia. announcements Unleash Your Inner Leader: Apply for the 2011 AALL Leadership Academy Law librarians in the early stages of your career— achieve your leadership potential by attending the 2011 AALL Leadership Academy, October 28-29, at the Hyatt Lodge in Oak Brook, Illinois. Train for leadership roles by discovering how to maximize your personal leadership style while connecting with other legal information professionals. Designed as an intensive learning experience aimed at growing and developing leadership skills, the program will include assessments, interactive discussions, small group activities, and mini-presentations. The academy will feature speakers Gail Johnson and Pam Parr. Johnson is a widely regarded leadership and communications expert and holds a master of arts in communication studies. Parr has extensive business management and customer service expertise. They have conducted many leadership programs for library organizations and will speak at the 2011 American Library Association Annual Conference. Applications are due by June 30. For more information and to apply, visit www.aallnet.org/prodev/event_ leadershipacademy.asp. Interested applicants should seek to obtain two professional recommendations (at least one from someone in a supervisory or managerial role). Please send recommendations to AALL Education and Meetings Assistant Vanessa Castillo at vcastillo@aall.org. Selected fellows will have an opportunity to obtain a mentor and receive ongoing leadership development opportunities. Apply today! AALL Spectrum ■ April 2011 11