WAL-MAO: THE DISCIPLINE OF CORPORATE CULTURE

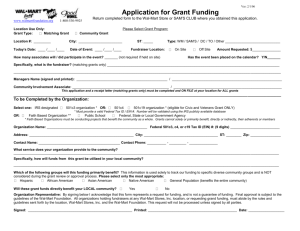

advertisement

WAL-MAO: THE DISCIPLINE OF CORPORATE CULTURE AND STUDYING SUCCESS AT WAL-MART CHINA David J. Davies∗ Wal-Mart, the world’s largest company, is famous for being nimble and flexible despite its size, constantly evolving through innovation and reliance on cutting-edge technology in transportation logistics and sales across a global network.1 One afternoon in the summer of 2005, Steve,2 a 27-year-old store manager at a Chinese Wal-Mart, offered a different perspective on the company’s success, one that emphasized its corporate culture. This culture, as every employee knows, is described formally in company training and depicted on posters and images displayed on the retail stores’ office and breakroom walls. Wal-Mart’s culture, Steve explained, is a comprehensive system that fosters positively-motivated employees and creates a unique work environment as the foundation of the company’s global success. During our conversation, he further offered a remarkable ideological lineage for the ∗ 1 2 Portions of this paper were first presented on the panel “China and the ‘End of History’: Critical Perspectives on Culture, Government and Civil Society” organized by Gary Sigley at the Fourth Annual International Convention of Asia Scholars held in Shanghai, 20-24 August 2005. Thanks to Laurie Duthie, Andrew Kipnis, Nelson Lichtenstein, Saul Thomas, Luigi Tomba, Jonathan Unger and two anonymous reviewers at The China Journal for their very helpful comments and valuable feedback on various drafts of this paper. I also benefited from the insightful questioning of students in my study-abroad seminar, Made in China: The Cultures of Economic Transformation. A number of recent essays examining Wal-Mart’s technological innovations can be found in Nelson Lichtenstein (ed.), Wal-Mart: The Face of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism (New York: New Press, 2006). Its social and economic effects are explored in Charles Fishman, The Wal-Mart Effect: How the World’s Most Powerful Company Really Works—and How It’s Transforming the American Economy (New York: Penguin Press, 2006). In the United States, negative descriptions of Wal-Mart have focused on its antiunion activities, its reliance on low-wage labor and discriminatory hiring practices, and environmental impacts. Liza Featherstone, Selling Women Short: The Landmark Battle for Worker’s Rights at Wal-Mart (New York: Basic Books, 2004); Al Norman, The Case against Wal-Mart (St. Johnsbury: Raphel Marketing, 2004). As noted below, it is common practice at Wal-Mart China for employees to use English names. Since employees, in effect, use pseudonyms while at work, I have chosen to give them new ones to offer a measure of anonymity. THE CHINA JOURNAL, NO. 58, JULY 2007 2 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 creation of that culture—assuring me quite matter-of-factly: “Sam Walton studied Mao Zedong Thought for five years before he opened Wal-Mart”. Chairman Mao’s ideology, Steve explained, had inspired the corporate culture designed by Wal-Mart’s founder. Walton, like Mao, had been born in a poor rural area and started from a base of committed colleagues. Ignoring large urban areas, he built an organization by consolidating power step by step. Only later did Walton, like Mao, move into cities and on to other countries using the revolutionary strategy of “the countryside encircling the city”. Today, Steve pointed out, Wal-Mart practices a kind of egalitarian management style among colleagues based on “servant leadership” not so different in tone from “serving the people”. The company’s emphasis on the security and stability of full-time employment, with bureaucratic grievance processes, was similar to the guaranteed “iron ricebowl” of state socialism. Didn’t Wal-Mart, like Mao, emphasize honesty as most important? Didn’t Wal-Mart even have its own dance demonstrating loyalty to the corporation? Even our conversation occurred beneath one of the many Walton images around the store, his hand raised in a benevolent wave reminiscent of the Chairman. The books that Steve and one of his colleagues offered as the source of their knowledge of Sam’s five-year study do not mention anything about it either in their English versions or Chinese translations.3 Apparently Walton never did read Mao. The relationship appears to be myth, in the anthropological sense, circulating among some Chinese Wal-Mart management.4 The lack of a historical relationship notwithstanding, Steve’s claim certainly had explanatory value—accounting for similarities between Wal-Mart’s corporate culture and his understanding of the Chinese socialist period. This paper draws on Steve’s “Wal-Mao” link as a metaphor for examining the localization of Wal-Mart’s corporate culture in China. Based on data collected from interviews, store tours, informal conversations and observations with current and former Wal-Mart managers at two stores in China from 2004 to 2006, it examines the ways in which the company’s corporate culture is translated, expressed, formally presented and enforced as a 3 4 Both thought they had read about the connection in The Wal-Mart Decade. This reference has been difficult to confirm because there are at least two different books available in China titled The Wal-Mart Decade, translated into Chinese as “Wal-Mart Dynasty” (Woerma wangchao). The first appears to be the official translation of Robert Slater’s (Luobaite Silaite) Woerma wangchao (Wal-Mart Dynasty) (Beijing: CITIC Publishing House, 2003). The second also appears to be a translation of a book by Licha Hamoer (Richard Hammer?), but I have been unable to locate a corresponding book in English. Licha Hamoer, Woerma wangchao (The Wal-Mart Decade), trans. Mo Wei (Tianjin: Tianjin Kexuejishu Chubanshe, 2004). Cf. the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss. Claude Lévi-Strauss, “The Structural Study of Myth”, in his Structural Anthropology (New York: Basic Books, 1963), pp. 202-12. WAL-MAO 3 means of disciplining behavior among management in China. 5 As a disciplinary structure, the “culture” rationalizes the day-to-day activities of individual employees across the transnational retailer’s thousands of stores. It is formally expressed in a Chinese context, however, in a moral language and tone in dialogue with Chinese associations of wenhua (᭛࣪), or culture, and the historical precedents of state enterprise culture under Mao. Correct practice of corporate culture claims to result in personal transformation and professional success and, at the same time, contribute to Chinese society more generally. After a slow start in the late 1990s, in the past few years Wal-Mart’s retail operations have been expanding aggressively in China—from 43 stores in 2004 to a projected 300 stores by the end of 2010. A significant challenge to this growth is hiring, training and retaining new retail employees. The projected growth necessitates adding nearly 3000 managers, 100,000 office staff and an additional 100,000 store employees within the next four years. The unending need for new staff makes Wal-Mart a relatively secure employer in China. The success of this dramatic expansion depends on mid-level management—a group of Wal-Mart employees often not considered in the critical examinations of Wal-Mart in mainstream academic and popular studies that have attracted so much recent media attention in the West. In China, Wal-Mart managers consider themselves part of the Chinese “white collar” (bailing ⱑ 乚 ) working class—a new class of private corporate functionaries that has emerged as China has been integrated into the global economic system. As “white collar” professionals they carry the dreams of future prosperity and global cosmopolitanism and are the subjects for whom the Reform period offers the most opportunity.6 They are also heavily invested 5 6 The initial data for this paper were gathered from a Wal-Mart store during a visit in 2004, and two longer periods in conjunction with an undergraduate study-abroad seminar in 2005 and 2006. During an extended research period in the spring of 2006 I collected data from an additional Wal-Mart store and from some of Wal-Mart’s competitors. The data include both formal and semi-formal presentations of Wal-Mart’s culture and participant observation at social events. As a private corporation, Wal-Mart has strict rules for dealing with outside inquiries for information. Members of Wal-Mart’s management, however, are generally proud of their corporate culture, confident in their work, and willing to talk about it. In one manager’s words, “we can talk about culture, but please don’t ask me about numbers”. Specific numbers in this paper were thus either provided by former employees or estimates given by competitors, or are cited from the literature. None of the “numbers” in this paper were provided by current employees of Wal-Mart, China. Laurie Duthie, “White Collars with Chinese Characteristics: Global Capitalism and the Formation of a Social Identity”, Anthropology of Work Review, Vol. 26, No. 3 (2005), pp. 1-12. Lisa Hoffman examines the aspirations of these professionals, economic competition and links to nationalism in what she describes as “patriotic professionalism”. Lisa Hoffman, “Autonomous Choices and Patriotic Professionalism: On Governmentality in Late-Socialist China”, Economy and Society, Vol. 35, No. 4 (2006), pp. 550-70. 4 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 in corporate culture discourses both as a means of doing their job and as a pathway to future success. Beginning with a brief discussion of corporate culture and enterprise culture under Mao, this essay summarizes how Wal-Mart’s corporate culture is deployed in its Chinese retail stores. Like the pre-reform period’s “work unit” (danwei ऩԡ) culture, Wal-Mart’s corporate culture is presented as a comprehensive “way of life” that unites employees’ work performance with personal and social morality. As store managers explain, they subject themselves to the culture because of the stress and uncertainty of China’s freewheeling (and often corrupt) market economy and in reaction to mainstream discourses that seek to demystify the sudden appearance of wealthy and successful entrepreneurs. Wal-Mart’s culture is seen as a reliable shortcut to “studying success” (chenggongxue ៤ ࡳ ᄺ ). “Wal-Mao”, this essay argues, is a useful metaphor for examining how corporate culture is presented, taught and policed as Wal-Mart localizes in China. In addition, it suggests ways that corporate culture articulates global and local aspects of transnational corporate power and influence, as it evokes utopian aspirations not so dissimilar from the Maoist ones that preceded them. “Corporate Culture” and the Ideal Modern Workplace A cursory search through both English and Chinese business literature yields hundreds of books and articles published on the subject of “corporate culture”. In these books, the concept of “culture” is used routinely either as shorthand for the unique character of an organization—its “brand”—or to summarize normative expectations for valued behavior within the organization. Asserting a “culture” assumes that organizations have different values and orientations within the larger socio–economic system outside of strict business. As “corporate”, however, the values and behavioral expectations are formally codified. The concept of culture referenced in this business literature is fundamentally different from the concept as commonly deployed by anthropologists. The latter see culture as a negotiated symbolic system that emerges in historical time rather than as a system of behavioral “software” available for managerial adjustment. Allan Batteau argues that corporate “organizational cultures” establish regimes of “goal-oriented instrumental rationality” concerned with imposing order for strategic ends. They do this by imposing “cultures of rationality, inclusion, command and authority” while simultaneously eliciting “cultures of adaptation and resistance” among members.7 While corporate cultures work toward distinct ends, they depend on the language, meanings, myths and values of culture in an anthropological sense, as it has emerged over historical time, to communicate their vision of order, establish boundaries, focus resources and promote the enterprise’s success. 7 Allen W. Batteau, “Negations and Ambiguities in the Cultures of Organization”, American Anthropologist, Vol. 102, No. 4 (2001), pp. 726-40. WAL-MAO 5 “Semantically”, Batteau writes, “they circumscribe order; poetically they imagine motivation”. 8 Corporate culture, in other words, draws upon the poetic associations and meanings of the larger socio–cultural context to communicate its messages of organization. In a Chinese context, even the term “corporate culture” (qiye wenhua ӕϮ ᭛ ࣪ ) evokes associations with the history of previous attempts at modernizing through culture. For much of modern Chinese history, the category of culture has been a central concept for orienting correct behavior, imagining order and circumscribing the Chinese nation. It is a foundational category central to thinking about modern social transformation and has a long history stretching from the late Qing debates about modernization, through the May 4th period, through the Cultural Revolution, to the present. Comprised of the characters for “writing” (wen ᭛) and “transformation” (hua ࣪), the word “culture” indicates the social transformations that take place when one becomes literate. As Angela Zito observes, these transformations involve social hierarchies and ways of being human. 9 The correct education of the behaviors and values of various “new cultures” have been indicators and metrics for modernity as well as for marking boundaries and justifying revolutions. 10 Discussion of what constitutes an appropriate culture and how to spread it through education has been seen as key to achieving a number of goals, from “saving the nation” to struggling for socialism or realizing the nationalist dream of “wealth and power” (fuqiang ᆠ ᔎ). During the last half of the 20th century, culture was tied to national modernizing projects through the state enterprise system and its “work units”—an ideal modern workplace that merged work, housing and social welfare together into a single site of both material and social production. While Cold War–era scholarship on work units took them as uniquely Communist institutions, a flurry of recent work links work units to preCommunist national political, economic and social trends. 11 These studies suggest that the system emerged as an urban organizational strategy designed to rationalize social behavior, inculcate nationalist ideology, enculturate new 8 9 10 11 Allen W. Batteau, “Negations and Ambiguities in the Cultures of Organization”, p. 726. Angela Zito, Of Body and Brush: Grand Sacrifice as Text/Performance in EighteenthCentury China (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1997), p. 58. Glen Peterson, Ruth Hayhoe and Yongling Lu (eds), Education, Culture and Identity in Twentieth-Century China (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2004). Morris Bian, The Making of the State Enterprise System in Modern China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), pp. 2-16; David Bray, Social Space and Governance in Urban China: The Danwei System from Origins to Reform (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005); Mark W. Frazier, The Making of the Chinese Industrial Workplace: State, Revolution, and Labor Management (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); Duanfang Lu, Remaking Chinese Urban Form (New York: Routledge, 2006); Xiaobo Lü and Elizabeth J. Perry (eds), Danwei: The Changing Chinese Workplace in Historical and Comparative Perspectives (Boulder: M. E. Sharpe, 1997). 6 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 national subjects, and organize economic production for state economic development. Thinking about work units also provided opportunities for imagining a modern utopian space—one confident in the power of rational planning to shape behavior and ideology. 12 Work unit culture made moral claims to remake its members. 13 The enterprise system also became central to the Chinese government’s exercise of political power and a primary source of the urban resident’s identity. As David Bray argues: It would be no great exaggeration to contend that the danwei is the foundation of urban China. It is the source of employment and material support for the majority of urban residents: it organizes, regulates, polices, trains, educates, and protects them; it provides them with identity and face; and, within distinct spatial units, it forms integrated communities through which urban residents derive their sense of place and social belonging.14 During the most radical political periods associated with Maoism, work units were both nationalist tools of nation-building and organizational units for political action, ideological work and the struggle for socialism. If urban danwei were a primary structure of the “new culture” of China’s revolutionary modernity, then perhaps in contemporary China’s era of global modernity, as private corporations emerge as the source of spectacular wealth and international attention, they are the new locations for inculcating new cultures—corporate ones. Such a proposition is not surprising given the fact that the Reform period was not established by asserting a comprehensive program, but informally in opposition to the Mao period by “crossing the river by feeling stones” (mo shitou guohe ᩌ༈䖛⊇) or other similar slogans. The mythical lineage that finds the roots of Sam Walton’s corporate culture in the fertile ideology of Mao Zedong Thought speaks to these associations. “Corporate culture” is in dialogue with both culture, as a category of social change, and the historical legacy of the organizational culture of the “work unit” as a place where culture and work were united. Steve’s assertion of a “Wal-Mao” relationship was shorthand for a variety of 12 13 14 David Bray traces the roots of the work unit’s institutional form to the imagination and planning of other utopian modernist projects in 19th-century Europe and America and later in the Soviet Union. David Bray, Social Space and Governance in Urban China. Similarly, Duanfang Lu analyzes the way that the built environment of urban China was reconstructed to meet the idealized vision of a modern utopian space. Duanfang Lu, Remaking Chinese Urban Form. Henderson and Cohen describe the way that work units struggled to balance the promise of Maoist egalitarianism with the hierarchical authority of the work unit leaders. This was primarily accomplished through a conception of the unit leaders that emphasized their moral character to lead. Gail E. Henderson and Myron S. Cohen, The Chinese Hospital: A Socialist Work Unit (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1984), pp. 140-45. David Bray, Social Space and Governance in Urban China, p. 4. WAL-MAO 7 Wal-Mart tactics, control mechanisms, policing and morality that resembled his understanding of the ethos of enterprise culture under Maoism. Wal-Mart Culture In his corporate history of Wal-Mart, Robert Slater provides an introduction to the corporate culture created by Sam Walton and expressed formally in its retail stores.15 According to Slater, the most elementary form of Wal-Mart’s culture consists of “three basic beliefs”: 1. Respect for the individual 2. Service to the customers 3. Striving for excellence. To this are added “ten rules of business” written by Sam Walton himself: 1. Commit to your business 2. Share your profits with all your associates, and treat them as partners 3. Motivate your partners 4. Communicate everything you possibly can to your partners 5. Appreciate everything your associates do for the business 6. Celebrate your success 7. Listen to everyone in your company 8. Exceed your customer’s expectations 9. Control your expenses better than your competition 10. Swim upstream. Walton added two more guidelines for daily employee conduct. The “tenfoot rule” mandates that “any time an employee comes within ten feet of a customer the employee is to look the customer in the eye and ask if he or she requires help of any kind”. The “sundown rule” stipulates that employees are “expected to answer requests by sundown on the day the requests are received”.16 Sam Walton intended that the foundational “beliefs” and “rules” would create an exciting and motivational atmosphere among store employees. The atmosphere was predicated on the ideal of each employee being aware and living out the corporate culture in dealings with other employees and customers. Walton believed that, if the employees felt good, then it would be easy “to make customers feel good being at Wal-Mart”—giving customers the impression of a warm, caring and personal “hometown” relationship.17 This corporate culture is shared across Wal-Mart’s stores globally. In fact, as its international division formally explains it, the success of Wal-Mart’s continued global growth depends on correctly moving and adapting this culture across national, regional and local differences: Despite obvious cultural and business challenges, Wal-Mart International has experienced success because of its ability to transport the company’s 15 16 17 Robert Slater, The Wal-Mart Decade (New York: Portfolio, 2003). Robert Slater, The Wal-Mart Decade, pp. 54-55. Robert Slater, The Wal-Mart Decade, p. 45. 8 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 unique culture and effective retailing concepts to each new country. The division makes a concerted effort to adapt to local cultures and become involved in the local community. Associates respond to customer needs, merchandise preferences and local suppliers. By serving each hometown in the same way, Wal-Mart International has realized significant growth with potential for much greater development worldwide [italics mine].18 Wal-Mart’s neutral language of cultural localization certainly suggests a benign exchange process. Culture, however, is used in this passage in two different senses—the corporation has a culture of “concepts”—ideas, methods, values—for operation, while the “local cultures” have needs and preferences to be served. Only by reducing local cultural difference to “preferences” or tastes is it possible to assert the contradictory claim to “serve each hometown in the same way”—to be the hometown supplier to local communities globally. The “transport” of Wal-Mart’s corporate culture to China certainly appears successful to Joe Hatfield, who until 2006 was the head of Wal-Mart’s operations in Asia. In a 2005 interview with Time Magazine, Hatfield spoke of his Chinese employees in glowing terms, adding: “The culture of Wal-Mart is stronger in China than anywhere else in the world”. 19 Certainly the principles of Wal-Mart culture are expressed clearly and ubiquitously at WalMart stores in China. Asking a frontline Wal-Mart employee about “Wal-Mart culture” (woerma wenhua ≗ᇨ⥯᭛࣪) often elicits a prompt recitation of the “three beliefs”, “ten rules” and the other guidelines. During my first formal visit to a retail store, Frank, a Wal-Mart regional manager, introduced Wal-Mart by gesturing to the crowded management office wall next to which we were standing, exclaiming, “This is our culture!” Affixed to the wall were four posters with various images and text that Frank told me would explain everything I needed to know about the company. Outside in the hall near the staff changing rooms was an even larger “culture wall” (wenhua qiang ᭛࣪) with further examples and explanations of the key aspects of Wal-Mart’s corporate culture. 20 Together this collection of posters presented the primary aspects of Wal-Mart’s global corporate culture as localized in China. Concepts are never simply translated cross-culturally, however, but are subject to recontextualization in new cultural milieus. The posters demonstrate how Wal-Mart’s concepts have taken on Maoist overtones in contemporary China. 18 19 20 walmart.com, International Operations: Global Strategy, Local Focus (Wal-Mart.com, 2007; available from http://www.walmartstores.com/GlobalWMStoresWeb/navigate.do? catg=369, accessed 19 March 2007. Dorinda Elliott and Bill Powell, “Wal-Mart Nation”, Time (27 June 2005), p. 38. Exchanges similar to my initial conversation with Frank occurred in subsequent visits with three different managers at two different Wal-Mart stores. Initial questions about corporate culture elicited a reference to the formal expression of the corporate culture on a “culture wall”. WAL-MAO 9 Sam Walton and Chairman Mao hand-wave The largest poster featured the benevolent fatherly image of Sam Walton. Dressed in a dark formal suit and conservative burgundy tie, his corporate image was softened by the simple working-class Wal-Mart baseball cap sitting slightly askew high on his head in rural American style. An everyday red, white and blue Wal-Mart employee nametag was pinned over his heart. Walton’s right hand is raised in a partial wave of greeting and his face has a muted expression of pleasant indifference. The conventions of such a posture are strikingly familiar to the religious images of the bodhisattva, Guanyin or even Jesus Christ. Drawing on more recent imagery, Walton’s pose is eerily similar to the images of Mao Zedong that circulated during the Cultural Revolution, hand raised in greeting at the top of Tiananmen gate, wearing his own symbol of unity with the masses—the armband of the Red Guard. By itself, the image of Walton might only be a curiosity and not extraordinarily remarkable. Like all images, however, its significance intensifies through reproduction. At one store I counted no less than five copies of the image in employee work areas, overlooking workers in the company cafeteria and hung along the employee entranceway leading into the store. Two additional copies were hung in public shopping areas. These were not different images of the founder in different poses, but reproductions of the exact image—which appears to be the only image of Walton in circulation at Wal-Mart China. 21 Beneath Walton’s image, in handwritten Chinese calligraphy, as if penned by the founder himself, was written, “pride comes 21 The use of this image also extends to Wal-Mart’s China website and can be found next to the “ten rules of business” at: http://www.wal-martchina.com/walmart/culture.htm, accessed 31 May 2007. 10 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 from outstanding performance” (zihao laizi chuse biaoxian 㞾䈾ᴹ㞾ߎ㡆㸼 ⦄).22 To the left of Walton’s image are the “ten rules of business”. In Chinese, however, the mundane tone of “ten rules” is replaced by “ten laws” (shige faze कϾ⊩߭) or “ten great laws for success of the cause” (shiye chenggong de shi da faze џϮ៤ࡳⱘक⊩߭). Similarly, the tone and associations of the translated laws shift from what might be glossed in English as a “language of marketing” to a Chinese vocabulary tinged with distinctly “revolutionary” connotations. Rule number one, for example, which in English is “commit to your business”, in Chinese says “be loyal to your cause” (zhongyu nide shiye ᖴѢ Դ ⱘ џ Ϯ )—a phrasing linguistically evoking other “great and glorious causes” (weida er guanrongde shiye ӳ㗠ܝ㤷ⱘџϮ) of recent Chinese history. 23 Rule number three in English speaks with the business tone to “motivate your partners”. The Chinese uses the word jili (▔ࢅ), to impel or inspire, a word used often in military examples of improving morale or in revolutionary-era party propaganda to inspire the struggle toward Communism. In English, rule number five asks employees to “appreciate the work that fellow employees do for the business”. The Chinese translation, however, replaces the simple congratulatory connotations of “appreciate” with ganji (ᛳ ▔), a feeling of heartfelt gratitude and indebtedness. Rather than simply “controlling expenses” as rule number nine asserts, the Chinese entreats employees to jieyue (㡖㑺) “economize” or “be thrifty”—a term familiar during Communism’s lean years in the 50s and 60s when Chinese citizenry were asked to “use less water” (jieyue yongshui 㡖㑺⫼∈) or “use less electricity” (jieyue yongdian 㡖㑺⫼⬉) for the greater good of production. Finally, in rule number ten where Walton challenges employees to “swim upstream”, the Chinese presents a similar phrase, to “go against the current” (niliu 䗚⌕), but adds an injunction in literary language to “forge new paths” (pi xijing 䕳䐞ᕘ) and to “not stick to conventions” (moshou chenggui ᅜ៤㾘). The point here is not to overstate the Chinese rules as dramatically different from their English originals, but to indicate the different poetic associations. The space between the original English and Chinese translation allows for a localization of meaning that defies a transparent term-for-term translation. Together, the “ten laws” present the corporate culture in language and associations reminiscent of revolutionary Communism and the many lists of rules for proper conduct articulated by the party. The “ten laws”, for example, are similar both in form and content to rules such as the Red Army 22 23 “Performance” in English contains both associations of efficacy or accomplishment of work and the acting, showing or expression of a particular behavior. The term biaoxian, which I have translated here as “performance”, has the associations of the latter meaning—the outward expression of a particular behavior. My translation, of course, plays with the polysemy of shiye, which can mean cause, enterprise or business. WAL-MAO 11 Code of Discipline’s Three Main Rules of Discipline and Eight Points for Attention (sandajilü, baxiangzhuyi ϝ㑾ᕟˈܿ乍⊼ᛣ), which stipulate obeying orders, frugality, interacting with others fairly and being honest in these interactions. Honesty and caring between employees is, furthermore, evoked by the “ten laws” through the formal use of tongren (ৠҕ) as a translation for “associates”. A fairly common term in Taiwan and Hong Kong, in Mainland China it is not as common as tongshi. While both Chinese terms may be translated into English as “colleagues”, the latter term tongshi ( ৠ џ ) emphasizes sharing common work, while the former tongren connotes shared humanity or morality between people.24 An assistant Wal-Mart store manager explained that, unlike tongshi, which is just a “co-worker”, tongren means “hearts united” (xinlianxin ᖗ䖲ᖗ) for a common cause or vision. Historically ren (ҕ), or “benevolence”, foregrounds the ethical qualities of personal relationships, and implies that they are properly constituted by subduing oneself to the proper social rituals of human interaction. The emphasis on work or morality implied by tongshi or tongren has displaced the common socialist era the term for “comrade”, tongzhi ( ৠ ᖫ )—someone sharing a common will or desire. The formal moral tone between “colleagues” (tongren) is reinforced in the language of the “gift policy” posted to the right of Sam Walton’s image. A rule throughout the Wal-Mart Corporation, this policy establishes that the giving of gifts and interactions of personal relationships is opposed to the rational function of the business between the company and its suppliers. It does so through a moral injunction against corruption. Given China’s giftgiving culture and the role of human relationships in doing business, the “gift policy” is a rule that is especially emphasized in the China operations.25 It is also the most thoroughly explained: No matter if one is a staff member whose duty is large or small, no one may, for his or her own personal benefit, accept any gift, tip, compensation, sample or anything that appears to be a gift. This is a basic principle of this company. 24 25 The associations of the term tongren seem to be inconsistent across age groups and regions. While younger workers seem familiar with the term, no doubt from working in foreign corporations, the older generation seems to associate it with ren. A colleague of mine from Beijing described the associations of tongren as reminding her of the Chinese four-character phrase yishitongren (ϔ㾚ৠҕ), which carries connotations of pan-human benevolence and equality that have a moral tone deeper than the fairly neutral term “colleagues” in English. Interestingly, the emphasis on social relationships that Mayfair Yang describes as emerging in opposition to state power during the Mao era is repositioned in opposition to Wal-Mart’s own corporate culture. Mayfair Mei-hui Yang, Gifts, Favors, and Banquets: The Art of Social Relationships in China (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1994). 12 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 These gifts may include: tickets for entertainment activities, commission paid in cash or products, a discount given to any staff member, sample products, travel paid for by a supplier, holiday gifts or other such gifts. Any staff member who receives gifts such as those outlined above is requested to please return it at the expense of the other party. Treating a guest to dinner is also a type of gift. If there is a need to have dinner with a supplier, staff from this company and the supplier should each pay their own costs. The principles outlined above are to be followed by all staff members of Wal-Mart and Sam’s Club. If you learn of an individual who makes any request for personal remuneration from a supplier, please directly inform a high-level company leader.26 Nearby two smaller individual posters described the “ten-foot rule”, modified in China to the “three-meter principle” (sanmi yuanze ϝ㉇ॳ߭), and “the sundown principle” (riluo yuanze ᮹㨑ॳ߭). The posters did not explain either of these parts of Wal-Mart’s corporate culture in great detail. It is, however, fascinating that, taken together, the two principles require that employees submit to a ritual of social interaction—appearing both engaged and friendly to customers regardless of underlying feelings. The ideal image of smiling workers and smiling customers evoke a “capitalist realism” perhaps not so distant in effect from the ruddy-cheeked workers smiling from socialist propaganda images. One Wal-Mart store even has mounted a full-length mirror near the employee lockers with the question “Are you smiling today?” written above, so that employees can “check their smiles” before heading out onto the sales floor. A final poster of Wal-Mart’s corporate culture, which appears to be unique to China, features the image of Joe Hatfield and outlines the “three basic beliefs”. The “beliefs” are translated into Chinese as jiben yuanze (ᴀॳ߭), or basic principles, implying a morality or rules for living. Above Joe Hatfield’s image, the value of these principles is explained: These [principles] are not simply rules for a style of work, but are “a kind of way of life”: we must take these convictions and dissolve them into every hour and every minute of our lives, embody them as colleagues and work together in the process of serving our customers. The culture formally codifies behavior for the corporation’s daily operations. They represent the company’s rules in a voice that borders on the religious—perhaps betraying a relationship to the southern rural American roots of Wal-Mart’s corporate culture. The ten “rules for business” translated as “laws” (faze ⊩߭) might even be translated more appropriately in English as “ten commandments”. Posting the commandments as guidelines for thought and action are not an unfamiliar American Christian practice. Joe Hatfield’s 26 Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own. WAL-MAO 13 call to take the basic principles as a “way of life” embodied through service to others certainly echoes Protestant Christianity’s emphasis on demonstrating belief through “living a Christian life”. These observations support Nelson Lichtenstein’s observation that Protestant Christian values infuse the discourse of American Wal-Mart stores. “Like the mega-churches, the TV evangelists and … motivational seminars”, he writes, “Wal-Mart is immersed in a Christian ethos that links personal salvation to entrepreneurial success and social service to free enterprise”.27 And yet, in a Chinese context, corporate cultural values have a different poetic cast—one with distinctly Chinese associations. The wenhua scripts a harmonious exchange among colleagues and between employees and customers. It projects a moral system onto relations typically considered exclusively economic. Thus, one does not need to believe in the principles and rules as a necessary precondition for them to be efficacious. Loyalty to the cause is demonstrated through their daily practice. Invoking “loyalty”, “inspiration” and “frugality” and “forging new paths” relies on the image of Walton and is authorized by the success of his legacy. At one Wal-Mart store, images of the founder were accompanied by a display of “corporate spirit” (qiye jingshen ӕ Ϯ ㊒ ⼲ )—translated, compiled and posted quotations from Walton. Printed in plain white lettering on a solid blue background and authorized by a copy of Walton’s own signature, the individual “Wal-quotes” were placed on the walls of the employee entrance. Staff ascending and descending the employee staircase from the city streets to the store pass nearly a dozen quotations and four images of the founder as they arrive and depart their work shifts each day. A selection of the quotations read: Strive to make customers return to shop at our store … only through this can we reap profits. Ensure the satisfaction of the customer, and they will continually patronize our store. Do not allow yourself to land in an unchangeable predicament. Listen to staff suggestions; they can come up with the best ideas. Make us work together as one to do our very best to market our products. Be grateful for every single thing our staff does for the company. Outstanding product marketers are able to guarantee a supply of product on hand to sell at all times. 27 Nelson Lichtenstein (ed.), Wal-Mart: The Face of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism, p. 18. Lichtenstein also observes how Christian references infuse Don Soderquist’s description of Wal-Mart’s corporate culture in his book, The Wal-Mart Way. Don Soderquist, The Wal-Mart Way: The Inside Story of the Success of the World’s Largest Company (New York: Nelson Business, 2005). The relationship between Wal-Mart’s corporate culture and Protestant Christianity is a compelling topic for further research, especially in the context of China’s reform-era religious revival. Cf. Richard Madsen, “Chinese Christianity: Indigenization and Conflict”, in Elizabeth J. Perry and Mark Selden (eds), Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance, 2nd Edition, (New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003), pp. 271-88. 14 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 Only by concerted efforts to reduce costs are we able to lower prices to the best of our ability. We must achieve true honesty. The difference between the competition and us lies in that we pay attention to cultivating staff consciousness about the products. To be more frugal with our expenses than our competitors is to fight for competitive superiority. It might be easy to dismiss the formal expression of a Wal-Mart “culture” as corporate propaganda designed to create the appearance of care where none exists. In other words, the “rules and beliefs” might be nothing more than a ploy to cover up a “deeper” corporate reality. Without denying this view, I suggest the possibility that the “rules and beliefs” have another use. Taken together they assert a system in which emphasizing the morality of correct behavior marks company membership—membership that is valuable among the predominantly young managerial workforce at a time where the rules for success in Chinese society are uncertain and in flux. The extent to which the corporate culture defines membership was illustrated to me by an exchange between some managers one evening as a group gathered for dinner. A member of the local Wal-Mart purchasing team, King, had been visiting the store and was invited to dinner by some store managers. He was a relatively new employee hired away from one of WalMart’s competitors. Other colleagues chided him about this and indicated his status as someone not entirely acculturated into the company, and perhaps morally suspect, by referring to him as the “half-bandit” (bange tufei ञϾೳ ࣾ )—using the derogatory term for the traitorous Nationalists during the Chinese civil war. When I asked King about the exchange he replied that even after months of working at Wal-Mart he was linglei (㉏), a different type of person from them—an “outsider”. Jane Collins and others have observed that transnational corporations have ruptured the bond of place that has historically linked consumers to producers.28 In China, of course, such an observation might be extended to include the reform-era reconfiguration of work and living spaces, and the social rules for work and production once unified under the concept of the work unit. As Michael Dutton suggests, the end of the work unit is a precondition of the “placelessness” that has come to mark the reform era.29 The codified moral instructions communicated through the “culture” posted on the management office’s walls certainly assert a community and define membership as they project a moral system onto employment relations typically considered only economic—providing a place and a corresponding 28 29 Jane L. Collins, Threads: Gender, Labor, and Power in the Global Apparel Industry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003). Michael Dutton, Streetlife China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 2122. WAL-MAO 15 new subjectivity amid the uncertainty of the present. When Frank directed me to the formal displays and proudly proclaimed that “it” was Wal-Mart culture, he was certainly speaking confidently and sincerely and without a trace of irony. Like nearly all of the other managers I met, he was at some level a believer, and the more I learned about his personal life, the more convinced I became that only some element of commitment, loyalty or belief could explain his cheerful disposition in the face of an unbelievable workload far from his family. This corporate membership, not unlike the forms that preceded it, represents itself as a total “way of life” that is affirmed through participation and enforced through a variety of surveillance techniques. It is the corporation as “way of life” and the utopian aspirations for ideal sociability and shared goals to which an association like “Wal-Mao” speaks. “My Wal-Mart”: Corporate Culture as a Way of Life “My Wal-Mart” is a popular slogan across the Wal-Mart corporation. The subject to whom the “my” refers is left open, permitting the slogan to speak broadly. Among employees the slogan asserts a claim of employee ownership, while it also suggests the individual attention to satisfaction that each customer can expect. In both cases, that Wal-Mart is “mine” as opposed to “someone else’s” sets an expectation for loyalty and commitment to the company. “My Wal-Mart” unites each individual employees’ performance with the success of the company even as it claims to satisfy individual consumers’ desires at the lowest possible cost. Wal-Mart’s corporate website projects this image through the stories of satisfied customers and postings through which individual employees speak of how “my Wal-Mart” took care of them in tough times or taught them new skills.30 At Wal-Mart, China, many employees wear a small “My Wal-Mart” (wode woerma ៥ⱘ≗ᇨ⥯) lapel pin. The pin provides the slogan in both English and Chinese—foregrounding the large Chinese characters for “my” (wode ៥ⱘ) and the large English word “Wal-Mart”, leaving the remaining Chinese and English words in the background. The effect makes the pin appear to read “wode Wal-Mart” a hybrid of both Chinese and English. At the top of the pin, in very small lettering, a question asks “Whose Wal-Mart is it?” The pin has two stars and is printed in the familiar American red, white and blue—adding, however, just a dash of gold, perhaps making the color scheme more similar to the Chinese national flag. Managers frequently highlight the extent to which individual employees— especially frontline employees—demonstrate the spirit of ownership to which a slogan like “My Wal-Mart” speaks. Staff members, for example, frequently design product displays, model for store advertisements and suggest new customer service techniques and ways to improve product sales. On a tour, Frank proudly showed off a huge airplane suspended from the ceiling above a 30 A selection of such narratives, many of which explicitly thank “my Wal-Mart”, can be found at: http://www.walmartfacts.com/lifeatwalmart/, accessed 31 May 2007. 16 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 product display that had been fashioned by employees from cardboard advertisements. They had creatively borrowed two floor fans to place under the wings as “jets” and had used a small ceiling fan as a propeller in the plane’s nose. A year later, the same store featured a display for a brand of mosquito repellent consisting of enormous Chinese characters fashioned out of product boxes suspended from the store ceiling. For managers, the creations—paper airplanes and big characters—were more than just advertisements; they were concrete examples of the worker creativity and initiative that flourish within Wal-Mart culture. They were symbolic indications of the freedom of expression and participation that Wal-Mart employees enjoyed. That they were also cobbled together from makeshift parts demonstrated frugality. While the displays were certainly invited by the corporation, just as models are solicited for advertising, the exact shape and form of the work was decided freely through the employees’ face-to-face work. At all of their stores, Wal-Mart uses face-to-face techniques to solicit worker input. Perhaps the most regular technique is the morning meeting held on the sales floor prior to the workday. Unlike the typical arrangement of similar meetings in Chinese companies, where management stands facing the workers in a military formation to do morning exercises and communicate important information, the Wal-Mart floor meetings are convened with management standing in a circle for discussion. When the manager speaks, he moves to the comparatively more vulnerable center of the circle to address his colleagues. At floor meetings managers of specific departments are praised for positive sales, confronted for lagging performance and encouraged to suggest improvements. More generally, faces, in the form of photographs, are posted regularly on management boards and checkout lanes, on sale products “sponsored” by a specific employee incentive, on performance boards posted near breakrooms, and on worker name badges. Responsibility for specific jobs and their resulting successes and failures is always tied to a specific face. The metaphor used commonly to describe the effect of the face-to-face meetings, voluntary participation and individual responsibility in store culture is that Wal-Mart is a “family”. Together Wal-Mart’s strong culture, its demanding work schedule and the young average age of employees result in an insular workforce where, as one manager observed, employees rarely like to deal with people outside of Wal-Mart and “take the store to be their family”. The culture is so strong that it creates, in Steve’s words, a “fundamentally different mode of thinking” from other organizations—especially local Chinese ones. Similarly to a family, he added, everyone has a unique role but they look out for one another, care for one another and show concern for the whole unit’s welfare and success. At Wal-Mart China, however, one could argue that many employees have little choice but to “take the company as their family”, as it creates so many dependencies and demands so much from a young workforce. Without exception, every one of the two-dozen or so managerial staff at the store level with whom I have interacted for the past three years is under 35 years old— WAL-MAO 17 the vast majority are in their late 20s. They were hired by Wal-Mart immediately following school and a few even worked their way up through the store hierarchy. The break-neck speed of Wal-Mart’s expansion in China has required that managers constantly be posted to new locations. When I met Steve, for example, he had just moved from south China; less than a year later he had moved again. The store had seen three different managers in three years, as seasoned managers were moved around to open new stores or aid at other stores. The work is so time-demanding that few managers seem to move beyond the immediate store vicinity and their residence. Given that all the managers I met were from distant cities and “outsiders” in the communities where they worked, it is not surprising that they would rely on the paternalistic security of the store as their family. One hard-working store manager who married within the Wal-Mart family has been separated from his wife for nearly three years as both took training and managerial positions at two different stores. The manager hopes that further expansion at Wal-Mart will enable himself and his wife to be united if multiple stores get built in the same city. If the store is a family, however, it is not thought of as a “Chinese family” with a rigid hierarchy but as the flexible, more egalitarian arrangement between “individuals” thought of as characteristic of American families. As Steve explained, “Chinese here at Wal-Mart live an American lifestyle and many readily take in American culture in their work habits, their individual lifestyle and their honesty”. Employee work habits were, he explained, laid out in a very structured and ordered way, with each individual’s responsibilities clearly described. As the training manuals and management materials attested, there was a plan to the work. This plan, however, was not the final word for every employee; “just like in America”, Steve pointed out that each employee can speak directly to any other employee—including a superior. He was proud that as a manager he was not immune to criticism. He explained: Before, at my old job, I had to listen to my boss and follow his instructions, but here [at Wal-Mart] any worker can talk to me. Working at Wal-Mart we practice egalitarianism (pingdengzhuyi ᑇㄝЏН) … for example, nobody calls me Manager Wu, they call me Steve. This is practicing the aspect of American culture of freedom and equality and respect for the individual … the female staff especially are really not used to this. This really is completely an American lifestyle. Emphasizing the egalitarian nature of work at Wal-Mart, every manager that I met has at some point or another commented on the fact that store managers do not even have their own offices, but share an office with the entire management team. When they were not working on managerial tasks in 18 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 the office they were expected to be out on the floor among the employees and customers.31 Among female employees, the structured nature of Wal-Mart’s culture provides a measure of protection from sexual harassment or discrimination. One female store manager, Sonja, agreed that women at Wal-Mart were more protected than in the workplaces of Chinese competitors. Wal-Mart has promoted a number of female employees to the store-manager level and in China there does not appear to be the same kind of gender imbalance noted until recently in American stores.32 Of course, female employees face other challenges. Many managers have commented on the tremendous stress that female leaders face in their relationships and marriages, where male partners might not be tolerant of long work hours or the conflicting commitments of the Wal-Mart “family”. Steve, Mark, two assistant managers and even the relatively new employee King all expressed the opinion at various times that “Wal-Mart culture is American culture” in the sense that it emphasizes individual lifestyles. This gives Wal-Mart, as a “way of life”, an association with an aura of urban—or even global—cosmopolitanism.33 As Steve expressed it to me, “Traditionally Chinese don’t want to leave home, but Wal-Mart employees travel to different cities and the company allows transfers between stores”. Wal-Mart offered movement between large Chinese cities, and it seemed that advancement generally occurred with moves to other locations. Moving from large city to large city to open new stores, to ascend management ranks and to gain new responsibilities is an exciting prospect for young employees. Initially I thought that the mobility of Wal-Mart management might have been intentionally instituted as a means to limit the formation of relationships that might lead to corruption. Mark told me, however, that similar movement takes place at Wal-Mart stores in the US and is one of the only means for advancement in Wal-Mart’s strict corporate hierarchy. Certainly, however, the regular movement of employees does have the useful side-effect of creating a primary affiliation with the corporation at the expense of local relationships. All of the managers I met at Wal-Mart stores in China commented on the difficulty of constantly getting used to new locations. One even commented that he had been in his current location for over two years and did not have a single friend outside of Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart’s global reach presents opportunities that certainly amplify this excitement. Every year, Wal-Mart China sends Chinese employees to stores in 31 32 33 Contrast this lack of offices to Lisa Rofel’s description of the spatial separation of management offices and the shop floors which reinforced hierarchy and provided privacy from the gaze of the workers during the Mao Period. Lisa Rofel, “Rethinking Modernity: Space and Factory Discipline in China”, Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1992), pp. 93-114. Liza Featherstone, Selling Women Short. Pheng Cheah and Bruce Robbins (eds), Cosmopolitics: Thinking and Feeling Beyond the Nation (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998). WAL-MAO 19 the United States for management training. Chinese managers who go to “study abroad” in the US learn about the larger corporation and the culture that founded it. Mark, a manager who had studied abroad in a small midwestern town for a year, explained that he returned to China with a deeper understanding of Wal-Mart’s American culture and of life in small towns. He was impressed with the friendliness of American employees, but also surprised at how much more hard-working Chinese employees were. He was grateful, however, that Wal-Mart had given him a great opportunity to improve his English—a valuable skill for communication and advancement. Even for managers and frontline workers who do not travel abroad, a significant moment of acculturation into the company—making Wal-Mart “mine”—begins with naming. Wal-Mart’s company policy stipulates that all Chinese employees are identified by English first names. If they do not have an English name when they join Wal-Mart, employees are “named” by their managers during training when they join the community of the global retailer. While frontline workers, most of whom speak little English beyond what they might have picked up in school, do not seem to use the English names in casual conversation, among managers the use of English names is much more common. A few managers even joked with me that they don’t know their coworker’s Chinese names. In her recent examination of the use of English names at foreign corporations, Laurie Duthie has argued convincingly that the practice of English naming is a marker of professional status—marking a worker’s position as a “modern Chinese” working in a global economy. 34 Certainly when a group of Wal-Mart managers eats together in public, or converse with one another in the store, the sound of English names interrupting the flow of a Chinese conversation mark them as individuals who can negotiate a transnational workplace. “My Wal-Mart”: Corporate Cultural Discipline The positive description of “My Wal-Mart” as a “family-like”, egalitarian, free corporate culture that emphasizes the value of the individual while fostering a spirit of cooperation is not simply savvy marketing. Attentive, smiling employees and cooperative, hard-working managers express the corporate culture on the sales floor. Store workers compete for sales, share ideas and comment at face-to-face meetings about performance and contributions to the store. Mark was grateful that Wal-Mart rewarded his loyal work with a “study abroad” opportunity. Steve seemed genuinely pleased with the cosmopolitan mobility of being a manager. Sonja felt comparatively protected by the company’s rule-driven corporate system that provided her with a dependable work environment. 34 . Laurie Duthie, “The Chinese Meaning of English Names: Shanghai’s Business Professionals and Western Naming Practices”, China Study, Vol. 2 (Fall 2005), pp. 49-73. 20 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 Yet, to focus exclusively on Wal-Mart’s corporate culture as it is formally presented would map marketing onto reality too closely—confusing the neat strategies of corporate culture with the messiness of culture as it is negotiated in daily life. One would not want to take the formal expression of an ideal corporate culture as proof of an “actually existing Wal-Martism”. Behind, under and around the assertion of corporate culture are a variety of “side effects” that render the workforce visible, coerce compliance and monitor workers. English names are a useful example of such a side effect. While English names are embraced—if mostly by the management—as markers of Wal-Mart identity, they are more than simply markers of global cosmopolitanism. According to one manager, all corporate correspondence is expected to take place in English. E-mails within the company system, for example, are written in English and signed by the English names of the employees, followed by either initials for the store location or the store number. The use of English names makes the Chinese managers visible to the international company, opening up the entire workforce to monitoring by English-speaking managers and corporate computer systems. While taking an English name, receiving training or going abroad may be formal examples of “My Wal-Mart”, the slogan has another, less formal usage that comments upon these “side effects”. At times, “My Wal-Mart” is invoked as sardonic commentary on the way the corporation individuates, isolates and disciplines individual managers. One evening over dinner, for example, King described how the manager of a nearby Wal-Mart store, Paul, was not doing well. He had moved up through the company to be a store manager, but had remained a poor leader. He was loyal to Wal-Mart, but the culture had made him too dependent and concerned with protocol or with offending subordinates. As a result, Paul had become a good part of the corporate machine, but not an effective leader. “That’s my Wal-Mart”, King said sarcastically—implying that Wal-Mart was not Paul’s, but that Paul had become Wal-Mart’s. The company discipline had made Paul a good follower, but had robbed him of the ability actually to make independent decisions that would make the store competitive. “My Wal-Mart” was also invoked to describe store purchasing. While most of Wal-Mart’s major competitors have a great deal of local control over purchasing, more than half of the goods at Wal-Mart are purchased centrally for distribution countrywide. According to a former employee, Carrefour, one of Wal-Mart’s main competitors, permits local stores to purchase up to 90 per cent of goods locally, reflecting local markets and local tastes. If more than half of the goods at a Wal-Mart store are purchased centrally, the brands and styles might be from areas unfamiliar to local customers and thus not sell well. Regardless of the fact that local managers have little control over purchasing, their effectiveness is measured by how much they sell. King described it thus: Wal-Mart just pays attention to the system, and not the people. But seriously, we should ask, does the system manage people, or should the WAL-MAO 21 people manage the system? [Wal-Mart] is like an ostrich with its ass in the air and its head in the ground … the culture is too closed … Wal-Mart can be too insular, seeing the world like a frog from the bottom of a well. And this has a huge impact on the ability to be competitive. The employee summed up his frustration by saying, “That’s my WalMart!” He used the corporate slogan to describe the way that the company held individual managers responsible for performing despite a corporate culture that shackled their decision-making. Mark, a store manager, described the feeling as being caught between “rules and reality”. It was a situation compounded further by the fact that WalMart’s strict corporate rules do not permit employees to accept gifts or have dinner with their vendors. He could not even have dinner with government officials, and “you know what China is like, everything is done over dinner! If a supplier asks me out for dinner, I tell them ‘I am sorry, but I cannot. Our company does not permit it’”. This can make Wal-Mart appear very strange in the eyes of other companies. The primary things over which store managers have control are the employees’ behavior and the customers’ experience at the retail stores. Managers cut costs whenever possible, but a primary goal is growing a customer base through offering a good shopping experience and the best possible service. Corporate culture is the primary means by which this experience may be controlled. Management insists that the culture cannot be demanded of employees; rather, employees must be convinced through effective education and modeling of behavior. In an earlier time one might be temped to use the concept of propaganda work. Store managers are expected to be the standard bearers of the corporate culture at the stores—the corporate cadres of “Wal-Mao”—modeling the behavioral expectations of the organizational culture for one another as well as the approximately five hundred employees and outside contractors who work at an average retail outlet. The success of Wal-Mart’s expansion, as managers explain it, is a cultural challenge, depending on them to model, teach and spread the organizational culture. They are the ones ultimately held responsible for constantly monitoring every aspect of store function. An extreme example of monitoring is the technological innovation that “pushes” hourly store data to store managers’ cell phones. Every hour throughout the day until 11:00pm, an hour after the store closes, store managers are notified of the volume of sales, number of customers, average total purchase and other information. The hourly data stream reminds the manager constantly of the ultimate sales goal. A cellphone message beep at the top of the hour is followed by a quick glance and an emotional response. A sunny weekend day might elicit a contented smile—indicating many customers and a high sales volume—while a rainy cold weekday might elicit a sigh and a comment to the effect that, “I am going to need an explanation to give my boss in the morning”. 22 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 That a store manager would even comment on needing an explanation to a superior for low sales on a rainy day speaks to the extent that store managers are watched by their superiors. Regional managers are sent regular electronic updates on store sales. This monitoring, however, does not only come from above. Managers are made most visible to their subordinates, as described explicitly in Wal-Mart corporate culture and directly enforced through methods, such as telephone hotlines, that are used to report ethical violations. As signs at the entrance of stores assert proudly, Wal-Mart practices “servant leadership” (gongpu lingdao ݀ Қ 乚 ᇐ ). This leadership style features an inverted leadership pyramid placing the store manager at the foundational “apex” followed by assistant managers and other managers above them. At the top are the “lowest” levels of managers. While the sign does not have room for a complete illustration, accompanying text indicates that the mass of workers is even higher and that the mass of customers is at the top. The sign illustrates the manager’s important role of “balancing” the pyramid from the crucial tipping point at the very bottom. From this servant position, the manager must “provide workers the opportunity for success”. The inverted pyramid image—putting the masses at the top—and the appeals to “serving” both customers and workers is strikingly evocative. It is similar to the appeals of the revolutionary new class hierarchy and the role of the post-revolutionary party leadership to “serving the people”. The similarities were not lost on Steve, who provided them as evidence of the WalMao connection mentioned at the beginning of this essay. A middle-aged friend of mine, who I accompanied on a shopping trip to the Wal-Mart store even described the language of “servant leadership” as a kouhao (ষো)—or slogan, reminiscent of the revolutionary past. Although the “servant leadership” poster is a formal statement to customers and employees about Wal-Mart’s values, it does provide workers and customers with a measure of power to make claims on managerial performance. As standard-bearers for the corporate culture, if managers do not perform the role of “servant leader” sufficiently or follow the “laws” stipulated by corporate culture, employees have a moral claim to criticize them and seek redress. A poster hung next to Walton’s “ten laws” articulates this moral claim most clearly. The notice, “Worksite Standards for Moral Behavior” (gongzuo changsuo xingwei daode guifan Ꮉ എ ᠔ 㸠 Ў 䘧 ᖋ 㾘 㣗 ) provides a telephone hotline and e-mail address for reporting ethical violations to WalMart’s ethics office in China or directly to the US. The hotline is clearly intended to catch serious violations of unethical behavior such as embezzlement, corruption or gift-giving. It does, however, also open the door for allegations of behaviors broadly defined as “harassment” (saorao 偮ᡄ) or “discrimination” (qishi ℻㾚). Because the hotline is anonymous, employees may use it to complain about any managerial behavior, no matter how small. While individual personality may mitigate an assertion of the rights to complain, serious or regular complaints by employees are investigated and some managers commented that it chills their effectiveness. This is especially WAL-MAO 23 true when compared to the cutthroat tactics of the local competition. In fact, more than one manager commented that Wal-Mart is so forgiving that it is an “iron ricebowl” (tiefanwan 䪕佁). Even in official store tours, managers describe how difficult it is to get fired from Wal-Mart. One manager offered an example, describing that he could not demand workers take shorter smoke breaks for fear that they would complain; instead, he had to “convince them” that it was not in their best interests, or the store’s best interest, for them to take more than the allotted time. Poor job performance is only dealt with though proper education and mentoring. The only behavior that will get an employee terminated immediately consists of a chengshi wenti (䆮ᅲ䯂乬)—an “honesty problem”. As Steve explained to me, honesty was the foundation of Wal-Mart’s work. Trust in this honesty is paramount and: Just as long as one does not have an “honesty problem” there is no problem. If a staff member is having a problem with their work, or is not performing well, we can teach them and train them. Just as long as they do not have an honesty problem. “Honesty problems” typically involve theft, offering kickbacks, or violations of the gift policy. The designation of this category is intriguing because it distinguishes between a physical component of work performance and a component of morality. While the system comes to the aid of an underperforming co-worker, an “honesty problem” speaks of something “deeper” in the quality of a person that might not be possible to resolve. The threat of consequences for honesty problems is greater in Chinese Wal-Marts where, unlike the United States, a majority of employees are full-time and have a larger investment in the corporation. Furthermore, Wal-Mart invests considerable time and resources training each employee in Wal-Mart’s culture of customer service. “Honesty problems” tend to be rare and it appears that the “iron ricebowl” of Wal-Mart employment has an exceedingly low turnover. Two employees described cases where employees who had left the company later returned seeking their old jobs. Both mentioned that after being with Wal-Mart for a while they were “not adapted” (bushiying ϡ䗖ᑨ) to life and work in another company on the outside—an effect of the workplace-as-lifestyle of “My WalMart”. “Studying Success”: From Mao Zedong Thought to Sam Walton Theory In an original book by a Chinese author that analyzes Wal-Mart’s retail strategy, Fangmeng Tian describes its corporate culture as “perfect” because it emphasizes and respects the individual, “thereby training the staff with a spirit of sacrifice and team spirit”. The success of Wal-Mart’s cultural training is a Wal-Mart spirit which Tian argues is a source of labor stability, and its recognition of workers reduces “labor turnover”. An important lesson of Wal- 24 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 Mart culture, he argues, is that the company must be responsible for its workers and that in return they will be loyal to it.35 The organization’s culture dictates that its success depends on each individual comprising it. Wendy expressed this best during a conversation: “It is just like our nametags say: ‘our people make the difference’”. The Chinese translation of that claim, however, is much more ambitious: “Our colleagues produce the extraordinary” (women de tongshi chuangzao feifan ៥Ӏⱘৠџ ߯ 䗴 䴲 ). In other words, the corporation creates, trains or empowers individuals who carry out extraordinary work, unlike other more mundane organizations. Such statements make claims that Wal-Mart employees are fundamentally of superior quality compared to average people. Indeed, job advertisements for Wal-Mart employees stipulate that they seek “individuals of outstanding quality”. In another book describing Wal-Mart’s retail strategy, Wang Xianqing describes “Wal-Mart people as different from the masses”. This difference, he argues, comes from the incredible success of a model of corporate culture that creates outstanding “loyalty”, an ethic of “hard-work”, and a “spirit of group unity”.36 And yet the advantages of the ideal system of “My Wal-Mart” come at the price of individuals subjecting themselves to a burden of supervision and discipline that also extends out from the company into their personal lives. As the sardonic readings of “My Wal-Mart” suggest, the system is emphasized over the individual. Despite the sacrifices, conversations with managers suggest that the opportunity to learn the “culture” of the successful global retailer is considered partial compensation for the high demands placed on employees’ personal lives, and for the low wages they are paid compared to their competitors. Taking the comments of Wal-Mart management and the secondary literature on Wal-Mart’s successful corporate culture together, one must conclude that Wal-Mart creates “high quality people”. The formal presentation of Wal-Mart culture suggests clearly that correct practice will improve an individual’s “quality” or suzhi ( ㋴ 䋼 ). Even the “negative” aspects of corporate discipline are seen as important to train oneself for competition in the marketplace. In contemporary Chinese corporate life the level of an individual’s suzhi may be referred to when rationalizing decisions about hiring, explaining work behavior, or channeling aspirations for future success. It is significant, however, that while suzhi is an important category of evaluation and speaks to a broad range of situations, there is no social agreement as to the specific means by which one may successfully increase one’s quality. This ambiguity 35 36 Fangmeng Tian, Woerma lingshou fangfa (Wal-Mart’s Retail Method) (Beijing: Zhongguo Shangye Chubanshe, 2002), pp. 25-26. Xianqing Wang, Woerma lingshou fangfa (Wal-Mart’s Retail Method) (Guangzhou: Guangdong Jingji Chubanshe, 2004). pp. 65-66. WAL-MAO 25 permits suzhi to be used to classify people without offering a dependable means for social mobility.37 This ambiguous relationship between “quality” and “success” has fueled a cottage industry of Chinese publications that define quality, and suggest how to increase it to achieve success. This genre of “studying for success” (chenggongxue ៤ࡳᄺ) dissects the lives of the famous and successful to arrive at underlying rules or principles of behavior to be emulated.38 Similar to Communist era models like Chen Yonggui, Lei Feng, Dazhai or Daqing, these individual and corporate successes are raised as examples to be emulated. Not surprisingly, Sam Walton is often discussed as a successful entrepreneur to be emulated. In one such book, Walton is described as a success story with “enlightening” lessons for contemporary Chinese who seek success.39 He was, we are told, a “high quality ordinary person” from a poor family who built his empire slowly and was “not eager for instant success or profit”. Long Shuai writes, “The contemporary success that Wal-Mart has reaped originated in its founder Sam Walton who was never content with the status quo and was highly dedicated to his cause”.40 Shuai offers an image of Walton as an average “man of the people” who even after becoming rich never changed his fundamental personality. He remained frugal. He was always on the move, and his management style involved frequent interaction with his employees. Walton succeeded because he was farsighted and established clearly-defined and attainable goals. “Furthermore, Sam Walton did not make the mistake that countless losers have made by being too eager for instant success”.41 Working at a successful foreign corporation like Wal-Mart is a shortcut to “studying success” where the quality control of corporate training, rigorous management, and cosmopolitanism intersect conveniently with assumptions for improving one’s competitive “quality” on the market. What could be more desirable, after all, than working at a company where the employees claim to 37 38 39 40 41 See Ann Anagnost, “The Corporeal Politics of Quality (Suzhi)” Public Culture, Vol. 16, No. 2 (February 2004), pp. 189-208; Børge Bakken, The Exemplary Society: Human Improvement, Social Control, and the Dangers of Modernity in China (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Andrew Kipnis, “Suzhi: A Keyword Approach”, The China Quarterly, No. 186 (2006), pp. 295-313. Examples include: Liguang Zhang, Zuoren jueding yisheng chengbai (Behaving Correctly Decides the Success or Failure of One’s Life) (Beijing: Zhongguo Shangye Chubanshe, 2005); Zhongli Zhang, Chenggongzhe de sishisige xinfa:chenggong bushenmi (Forty-Four Rules of Successful People: Success Is Not Mysterious) (Tianjin: Tianjin Kexuejishu Chubanshe, 2005); Zhiqing Zhang and Jieyun Zhang, Chenggongshu: gaosuzhi rencaide moshi yu suzao (The Tree of Success: Models of High-Quality Talent) (Beijing: Dizhen Chubanshe, 2005). Long Shuai, Suzhi jueding chengbai (Quality Determines Success or Failure) (Chengdu: Sichuan Wenyi Chubanshe, 2005), pp. 188-97. Long Shuai, Suzhi jueding chengbai, p. 193. Long Shuai, Suzhi jueding chengbai, p. 197. 26 THE CHINA JOURNAL, No. 58 “produce the extraordinary?” Even the moral language of discipline, anticorruption and loyalty of Wal-Mart’s corporate culture resonates with the moral overtones of self-cultivation found in suzhi.42 In effect, corporate culture, in the case of Wal-Mart, becomes an engine of transformation that is not only economic but socio-cultural. Rachel Murphy suggests that suzhi discourse enables the Chinese state to shift from welfare support to an emphasis on helping citizens to improve their “quality”. 43 If private global corporations are one path for improving that quality, then private corporations become another tool for the transformation of China into a “strong nation”. Conclusion Seeing the corporation and the successful adaptation of its culture to the host country as the latest in a lineage of revolutionary claims to transform Chinese society might offer a means to understand the startling lineage that links the inspiration for Wal-Mart’s corporate culture to the thought of Mao Zedong. On a basic level, the Wal-Mao myth ties together a number of superficial similarities and poetic associations between the way that Wal-Mart culture is deployed in a Chinese context and the formal presentation of revolutionary culture. The myth also short-circuits the post-Mao lineage of Reform to tap directly into the legacy of Chairman Mao himself—potentially making Sam Walton the heir to Mao Zedong thought and Wal-Mart a revolutionary force. It speaks to utopian dreams of success by uniting corporate culture and daily routines with the goals of national development, prosperity and equality. Interestingly, “Wal-Mao” also offers its own critique of the Reform era by providing a system that seems preferable to the unknown rules of wealth generation and rampant corruption of the relatively “chaotic” system of capitalism outside Wal-Mart’s doors. Its culture asserts a corporate moral behavior that makes confident claims to transform its employees, to model behavior for customers and thereby to influence Chinese society at large. These fervent claims for the corporation and its mission are surely a kind of revolutionary “utopian capitalism” that often bears an uncanny resemblance to the utopian socialism which preceded it. It is a future of low prices and smiling faces where profit is secured by order and workers are disciplined for the greater good of capital. Good customer service becomes the practice of morality and if everyone is of proper quality, the system will be stable with plenty of consumption to go around. The corporation is one which intends to “serve the people” with a new “mass line” of high-volume sales. Wal-Mao is a metaphor for examining the localization of Wal-Mart’s transnational corporate culture in China. It resonates poetically with a wide spectrum of language, activity and experience with Wal-Mart’s corporate 42 43 Andrew Kipnis, “Suzhi: A Keyword Approach”, pp. 306-10. Rachel Murphy, “Turning Peasants into Modern Chinese Citizens: ‘Population Quality’ Discourse, Demographic Transition and Primary Education”, The China Quarterly, No. 177 (2004), pp. 1-20. WAL-MAO 27 culture. Wal-Mart, however, is a relative newcomer to the Chinese retail market. While it is a powerful company globally, within China there are still many larger and more influential companies, both Chinese and foreign-owned. As a result, the details of “Wal-Mao” may be unique to Wal-Mart, China. Nevertheless, the case examined here suggests that corporate culture can speak to the transformations of reform-era Chinese society and the new regimes of moral self-making. The creative ways that corporate culture formally imagines order and disciplines behavior makes it an heir to the danwei in uniting correct culture with modern production.