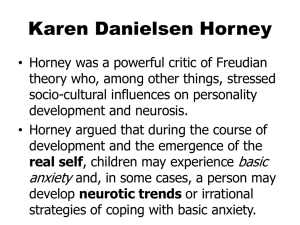

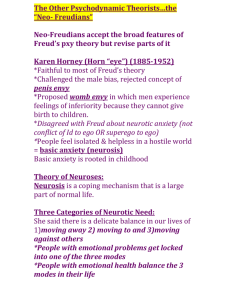

4 Karen Horney Psychoanalytic Social Psychology

advertisement