N L R C L A W R E P O R T July 2013

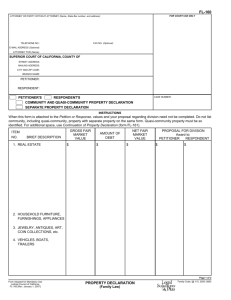

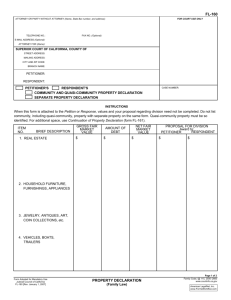

advertisement