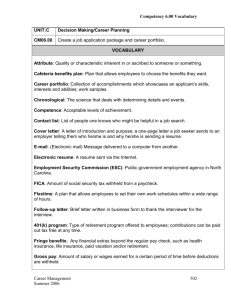

CCMAil- October 2010

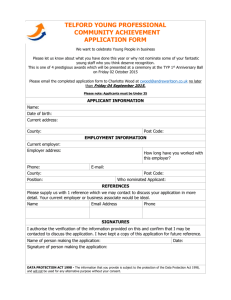

advertisement