Fifty Years in Fireworks - Brigham Young University

advertisement

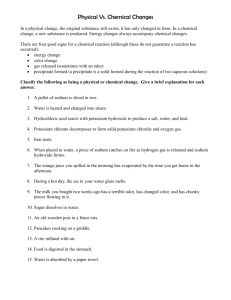

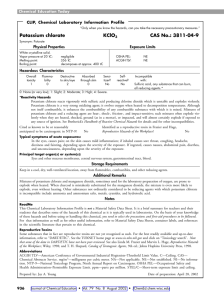

P OTA S SI U M C H L OR AT E A N D M E : F I F T Y Y E A R S I N F I R E WOR K S Wesley D. Smith—Department of Chemistry A s a youngster, I was like any other kid. I loved fireworks. Whenever my father brought home a carton of candles and fountains for the Fourth of July, I was thrilled. Whenever other boys peddled bootleg firecrackers at school, I was a buyer. And whenever anything burned with a sparkle or a bang, I was fascinated. Had my circumstances remained typical, this childhood infatuation would probably have mellowed over the years into a normal adult’s “ooh and ahh” appreciation of aerial displays. But, instead, a watershed event occurred that fanned my spark of interest into a flame of pyrotechnic passion that has lasted my whole life: at age seventeen, I was introduced to potassium chlorate. SK Y RO C K E T S I remember the very day. A couple of blocks from home, I happened to run into Bill McClanahan, a classmate whom, at the time, I knew only in passing. “You want to see something?” he asked, opening the shoebox he was carrying. “Sure,” I said. From the box he produced a homemade skyrocket. It consisted of an inch-long cylinder made of newspaper. It was about half-an-inch in diameter, and it was taped to the end of a drinking straw. A short piece of brown fuse protruded from the cylinder. “Want to see it go?” Silly question. So, right there, in front of some stranger’s house, Bill pushed a straightened coat hanger into the lawn. Then he readied the skyrocket by threading the drinking straw onto the wire. He struck a match, and lit the fuse. With a loud pfft, the rocket shot 00 or 200 feet into the air. And my heart soared with it. I suddenly had a million questions, and Bill was glad to answer every one of them. We were soul mates. There were three design features of Bill’s rocket that I would never have thought of myself. The first was the ingenious combination of the drinking straw and coat hanger as a launch mechanism. It meant that the rocket could be guided, with little drag, on a straight-up path during the critical initial moments of flight. The second was the fuse, a commercial product designed to ignite Jetex engines, the 950s precursor to Estes model rocket motors. It was readily available in hobby shops—even to teenagers. The third, and most alluring, was the rocket propellant itself. WAYS OF KNOWING • 43 It was a simple mixture of ordinary table sugar and a magical white powder called potassium chlorate. Bill showed me his huge bottle of it, and he told me how I could order my own through the mail. I immediately perceived the significance of these features. They meant that all the means and materials necessary to manufacture skyrockets were now in my own hands. I no longer had to remain on the sidelines as just some pyrotechnic spectator. I could make fireworks happen for myself. Over the next year or so, Bill and I, both together and separately, made rockets continually. Studies, sports, and work competed for my own time, of course, but I probably averaged one or two launches a week. My father, in his personal history, recorded that I “had rockets flying all over the neighborhood during [my] high school career.” S C I E NC E I tinkered with the design of the rocket casing. When I rolled the paper cylinder, how sturdy did it have to be? More layers of paper meant added strength, but they also meant added weight. How big of a nozzle was just right? Too wide an opening caused the rocket to fizzle out. But too narrow a nozzle caused it to blow up. I also investigated the composition of the propellant. How much potassium chlorate should be added to the sugar? Too little or too much weakened its performance. Would potassium chlorate burn as well with other common substances? I tried mixing it, for instance, with powdered charcoal and with baking soda. The former combination burned; the latter didn’t. Almost forty years later, I would publish two technical papers in a scientific journal. One was on the mathematical design of model rocket motors, and the other was on the chemical formulation of pyrotechnic mixtures. But that’s getting ahead of the story. I did not realize it in high school, but I was already doing science. BY U My mother was often stereotypical. Worried about my pyrotechnic puttering, she would say to me, “You shouldn’t be playing with that stuff unless you know exactly what you are doing.” So, when I went away to college at BYU in Provo, I majored in chemistry. The full reasons for choosing that major were actually more complex, but the chance to exonerate myself with my mother without giving up fireworks was certainly a contributing factor. While at BYU, I learned that potassium chlorate, KClO3, was synthesized in 786 by the great French chemist, Claude Berthollet. 44 • PERSPECTIVE He was hoping to replace the then-scarce potassium nitrate, KNO3, in gunpowder, but that didn’t work. He did discover the potassium chloratesugar mixture and the fact that it could be ignited without a spark. One needed only to dip it in sulfuric acid. Thus he made one of the first matches, briquets oxygPnes. I also learned that potassium chlorate was an example of an oxidizer, a substance lacking in sufficient electrons. An oxidizer would thus react vigorously with a fuel, a substance brimming with surplus electrons. And my early combustion trials began to make sense. Charcoal was a fuel, and baking soda was not. In freshman chemistry laboratory, I actually used potassium chlorate in fully sanctioned experiments. Heated with a catalytic pinch of manganese dioxide, potassium chlorate was the standard source of oxygen gas. Outside the laboratory and little out of bounds, I found that adding a bit of manganese dioxide to my rocket propellant made it burn faster and gave it an exciting increase in thrust. M I S S ION In 962, I was called to the Central American Mission: Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. To my delight, the local Catholic customs required daily launchings of “blessings” (skyrockets with double salutes) into the heavens. And there were a number of craftsmen, called coheteros, who manufactured them in every town. The rocket casings were made of bamboo, taking clever advantage of the wood’s natural compartments. The propellant was gunpowder. And the salutes, or the components that exploded with a bang, were made of sulfur mixed with … potassium chlorate! The composition was confined with many wrappings of twine and a coat of shellac. Without confinement, the mixture just burned. My new knowledge that potassium chlorate could explode with sulfur led to an infamous incident in Nicaragua. One p-day four of us missionaries went fishing on a deserted pier. I quote from my journal: WAYS OF KNOWING • 45 We decided to celebrate with a little noise-maker I had brought. It was a pipe capped at one end. You fill the bottom with potassium chlorate and sulfur, stuff paper down the other end, and light it with a fuse. It’s perfectly harmless, but it makes a whale of a boom and a cloud of confetti. We lit it off and went back to our fishing. Pretty quick a custom’s official came and wanted to know what happened, so we showed him. Then six soldiers came and rounded us all up, fishing lines and all. We were detained—in jail—for almost three days. Back then was a relatively innocent time; 9/ was just the day after the tenth. Nevertheless, we had great difficulty explaining what we, as mysterious foreigners, were doing with all the makings of a pipe bomb (except for one end cap). At length, the mission president was able to negotiate our release. Following very stern instructions from him, I never again touched fireworks on my mission. Still, I tracted out every cohetero I could find, and I taught them the gospel. I had some success, too, because I spoke their language. M A R R I AG E After my mission, being somewhat more mature, I entered a period of reduced pyrotechnic activity. Back at BYU, I decided that I liked the mathematical aspects of chemistry, and, more than that, I liked the idea that I could explain them in terms other people could understand. So I focused on a graduate degree with the goal of teaching chemistry at the university level. Plus, I got married to Jean Oliver of Bountiful, Utah. That is not to say I ignored fireworks entirely. I dabbled in them from time to time. One day, in the first year of married life, I got to thinking about potassium nitrate and sugar. Like my rocket propellant, this, too, was a powerful oxidizer-fuel mixture, but it could actually be melted without igniting. In the past, I would pour the caramel-brown liquid on waxed paper and let it solidify into disks, which I called “cookies.” They would burn when lit to give copious amounts of white smoke. (Homer Hickam, the author of October Sky, moltened the same mixture in his youth. But he called it “candy.”) I began to wonder if my rocket propellant could be melted also. In other words, could KClO3 substitute for KNO3 in the “cookie” mix? I found out on the stovetop of our basement apartment. The answer, like Berthellot’s, was no. The mixture caught fire long before it melted, and it produced huge volumes of black soot in addition to great clouds of white smoke. The whole kitchen was covered with smudge, and the rest of the apartment acquired a burnt-sugar smell. My wife, even sterner than my mission president, made me scrub the floors, the walls, and the ceiling. Then she imposed draconian household restrictions on 46 • PERSPECTIVE me and my chemicals. All in all, it was the least convenient scientific fact I have ever learned. M I DW E S T After earning my Ph.D. from BYU and after doing some post-doctoral research at the University of Utah, I got my first faculty position, a 3year teaching appointment at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. There, I associated with Bassam Z. Shakhashiri, a prominent chemical demonstrator. And I was trained in the technique of showing chemistry in the classroom, not just talking about it. Among the many striking chemical demonstrations that I learned there was the Gummy Bear reaction. It became a fixture in my teaching, and I do it for every class. I drop a gummy bear into a test tube of—what else?—molten potassium chlorate. Then for the next 20 or 30 seconds, the sugary little figure is spectacularly consumed in a frenzy of flashing flames. (See a video of the reaction at http://www.public.asu.edu/~dleedy/gummy%20bear.mo.) Watching it is an unforgettable experience. Ask any of my former students. After Wisconsin came a tenure-track position at Illinois State University in Normal, Illinois. We attended the only Normal Ward in the church, and I began serving my fourth stint as Scoutmaster. There, circumstances finally aligned so that I could take Scouting’s top leadership training course, Woodbadge. In the course, participants are assigned permanently to one of several rival patrols with traditional names such as Bears, Owls, or Bobwhites. Woodbadge mystique makes association with a particular patrol a lifelong distinction. The culminating event of the training is a grand gathering in which the ceremonial campfire is customarily started in some innovative way, as with a flaming arrow, for instance. My patrol, the Eagles, drew the assignment. When the formal moment arrived, all was dark. Suddenly, several lengths of fast-burning fuse popped, and all the patrols were dazzled with six tall letters, each shaped of brightly colored flames. They spelled EAGLES. Good ol’ potassium chlorate and sugar. This time, however, the mixture was spiked with various additives: strontium for red, barium for green, sodium for yellow, and copper for blue. R IC K S C OL L E G E In 98, I came to Ricks College, and I began living two of my dreams. One was a powerful, life-motivating dream. Ever since I visited Ricks around 976, I had longed to teach in an LDS environment. Just walking the campus sidewalks, I sensed an ambience unlike any at Wisconsin or Illinois State. The Spirit of Ricks was inspiring me—decades before it had acquired a name. Now that dream had come true. The other was WAYS OF KNOWING • 47 more of a fantasy—a low-priority, pie-in-the-sky notion. I had often thought it might be fun to apprentice myself to a fireworks maker and learn the trade. I had never run across anyone in the Midwest who could teach me, but it was only a matter of days in Rexburg before I met Dave Hannah. A printer at the College Press, he moonlighted as an aerial shell manufacturer. Thanks to him, I fulfilled my other dream. Dave built the salutes that were fired after touchdowns at the football games. They were simple canisters filled with flash powder, a mixture of potassium chlorate (or its tamer cousin, potassium perchlorate, KClO4) and very finely powdered aluminum metal. Unlike the Central American chlorate-sulfur mix, this composition exploded without confinement. Even on an open surface, a pile of it would blow up with a chest-thumping boom. Special safety precautions were required in handling flash powder—it was especially sensitive to static electricity, for example—and Dave made sure I knew them thoroughly. Dave also introduced me to Pyrotechnics Guild International (PGI), an association of fireworks enthusiasts from all over the world. In the summer of 989, we went together to PGI’s annual convention in Jamestown, North Dakota. A whole new world of fireworks opened up to me during that week. I was trained in fireworks display safety, and I became a PGI Certified Shooter. I built and fired a three-inch ball shell with my own hands. I networked with experts in every aspect of the fireworks trade. And I became seriously involved. My era of reduced pyrotechnic activity had ended. From books and journals, I dug out all the technical aspects of pyrotechnics. I studied not only the how-to instructions for crafting different fireworks effects but also the scientific explanations for why they worked. I helped Dave put on big displays in Rexburg, Idaho Falls, Jackson Hole, and elsewhere. I corresponded with several pyrotechnic masters, and I attended more PGI conventions. In a few years I rose from a semi-knowledgeable tyro, known to PGI veterans—so aptly in my case—as a “basement bomber,” to a level of professional expertise that would finally put my mother at ease. I gave short courses in the chemistry of pyrotechnics all around the country. When the scientific Journal of Pyrotechnics was started, the publishers appointed me to the four-man editorial board. And when the PGI held their 20th annual convention, I was the chairman; and I brought it to Idaho Falls. Academically, fireworks became my chemical specialty. Much to the concern of administrative staffers from here to Salt Lake City, I set up a small laboratory in the Romney building for pyrotechnic 48 • PERSPECTIVE research. They had nightmares that, because of me, the whole northern part of campus was going to be vaporized into a smoldering crater. But in reality I was formulating mere gram-sized compositions, and I was studying a delicate table-top fireworks effect called senko hanabi with its tiny branching sparks. Student Bunsen burners were making bigger flames. Nevertheless, they were all relieved when new instruments in the chemistry department required me to relinquish the space. 8 2 O V E R T U R E In 995, Kevin Call, conductor of the Ricks College Symphony Orchestra, invited me to help him with a production of Tchaikovsky’s 82 Overture. It is the only score I know of with a line of music written specifically for cannons. In fact, cannon shots are called for seventeen times in the body of the piece. So, to prepare, I made some flash powder, put it in a special theatrical device called a flash pot, and tested it on the stage of the Barrus Concert Hall. I wanted to see if it would be a suitable substitute for a literal cannon shot. The thunderous blast that followed rattled the doors, knocked open some overhead light fixtures, and caused a rain of grit to fall from the ceiling. Prudently, I opted for a milder mixture, potassium nitrate and magnesium powder, for the actual performances. Still, it was uproarious as I, the featured “musician” in white tie and tails, flipped switches on my control panel and rocked the hall with my salutes. It’s a shame no one has written more music for my instrument. E UG E N E K L I NG E R In 996, after fourteen years at Ricks, I was doubly eligible for an academic sabbatical. I had several options under consideration, and I was favoring the possibility of working with a pyrotechnic chemist I knew at Arizona State. But my wife (and spiritual compass) felt I should let go of the fireworks notion and accept a sudden invitation to be an ambassador for Ricks College in Kharkov, Ukraine. I dragged my feet a little. The former Soviet Union represented the ultimate foreignness to me. But I knew it was wise to honor Jean’s judgments in such matters. So, on our thirtieth wedding anniversary, we found ourselves on an airplane headed toward Eastern Europe and into adventures unknown. A Ukrainian national holiday happened to fall within the first weeks of our arrival, and I was thrilled to learn that they would celebrate it with fireworks on the great square near the university where I had begun teaching. Eagerly, I arrived early on the square to inspect the set-up. Shooting sites need security because unrestrained people, like me, WAYS OF KNOWING • 49 tend to crowd ground zero. But there would be no encroachment that night. Literally hundreds of uniformed soldiers, armed with Kalashnikovs, already stood shoulder-to-shoulder around the entire perimeter of the site. So, when the show began, I had to observe the aerial bursts from an unaccustomed distance. Nevertheless, I looked with a practiced eye for some new effect that I might learn. Instead, I noticed a conspicuous lack of one common fireworks color. There were reds, greens, golds, and whites, but no blues. “I can teach them to make blue flame,” I thought smugly. I found out who “they” were at the end of that week. Downtown, on a billboard, was what seemed to be an advertisement for fireworks. Mostly illiterate, I had one of the missionaries translate the Russian words for me. It was better than I had hoped. The sign was about a fireworks factory right there in Kharkov, and the information included an address and phone number! I immediately arranged with the Elders to go with me in a few days to tract out these Ukrainian coheteros. But I couldn’t wait. I followed a city map, and I went to the factory by myself. Boldly, I marched into the office and presented my card to the receptionist. I gushed one of the few phrases I knew in Russian, “I, chemistry professor.” (I had just recently learned it, together with the correct “me Tarzan” syntax.) But I was unable to communicate further. Frustrated that she could not get me to understand anything, even when she spoke loudly, she signaled me to wait while she went for help. She returned with none other than Eugene Klinger, who, I would find out, was the foremost fireworks expert in all of the Ukraine. He spoke fluent English. “Are you a member of PGI?” he asked, after learning that I did fireworks. “Do you know Fred Olson III [a PGI acquaintance of his]?” “Yes and yes!” It was a remarkable coincidence, and I was instantly accepted. We talked for two hours. Somewhere in the conversation, I tried to impress him by offering my formula for blue fire. But he didn’t salivate. He already had dozens of his own. In fact, he understood the formulation of pyrotechnic mixtures far better than I did. The absence of blue in the display derived not from a lack of know-how but from a local scarcity of certain chemicals. I was the one who was impressed. Eugene and I became fast friends. Every Tuesday night for the next nine months, he came to our apartment for dinner. Afterwards, he and I would discuss pyrotechnics, argue scientific principles, and write technical papers. Indeed, it was with him as a co-author, that I published the two papers I spoke of earlier. In addition, we wrote about the construction of optimally-loud firecrackers, the engineering of nozzleless rocket motors, and the efficiency of packing stars in spherical shells. It was the most prolific collaboration of my scientific career. And it was beneficial for 50 • PERSPECTIVE Eugene, also. “You are the first person I’ve ever known who understands my work,” he told me. My connection with Eugene was but a fraction of the value I gained from my Ukrainian sabbatical. More than anything, the experience infixed in me the truth that God, if I follow him, has a grander plan of happiness for me than any I could orchestrate for myself. M E R I T BA D G E S The allure of fireworks for young boys is no less powerful today than it was fifty years ago. I have tried to be a resource to interested youth so that the can learn the fascinating principles of pyrotechnics safely and openly—in a way their mothers can support. Scouting’s Chemistry Merit Badge has been my introduction to many boys. I generally entice them with the proposition that if they earn the merit badge, I will show them how to build a skyrocket. And, over the years, I have signed the merit badge cards for more than 900 of them. Less often, I have been counselor for the Wilderness Survival Merit Badge. One of the requirements is to “show that you can start fires using three methods other than matches.” The obvious implication is that these methods should be useful in survival situations. I teach them the practical techniques, but shamelessly living the letter of the law while ignoring spirit thereof, I also show the boys briquets oxygPnes (with potassium chlorate) and several other exotic chemical ways to light fires without matches. None has complained. S M I T H A N D WI L DE In 998, I obtained a federal license, and I took over Dave Hannah’s fireworks business. Together with a young partner, Jeff Wilde, I established Smith and Wilde Fireworks. We continued to shoot salutes at football games. We supplied fireworks shows for most of the small cities around eastern Idaho. We did the Fourth of July extravaganzas for a group of rich doctors in South Dakota. They liked to brag that their annual private shows were bigger than their city’s displays. For the past five years, all the University fireworks shows and the International Folk Dance displays have also been put on by Smith and Wilde. All this work gave me a chance to choreograph aerial displays. Anyone can fill the sky with aerial bursts. That type of show, known in the PGI as a “carpet bombing,” is exciting for about a minute, and then it gets boring. On the other hand, an artistic display uses pace, contrast, and rhythm to sustain interest. I tried always to produce the latter. Audiences have judged the success or failure of that effort; but it has been fulfilling for me, a left-brained theoretical chemist, to be in my right mind. WAYS OF KNOWING • 5 I have now retired from commercial fireworks—not from the smallscale art and science of pyrotechnics but from the financial and regulatory pressures of being a display operator. One of the signs that my time had come was when the Rexburg Fire Marshall and three other officers showed up at my office in the Romney Building. For thirty minutes, they took me to task for neglecting to obtain a city permit for one of the University’s fireworks shows. My colleagues down the hall thought surely I was going to be hauled off in handcuffs, and I sweated bullets that they might be right. I have elected not to push my luck any further. HOBB Y FI R E WOR K S Family and church have always been the focus of my life. But fireworks, as an auxiliary activity, have been endlessly exhilarating. I shall ever be thankful for potassium chlorate, the stimulus substance. “Behold I have created the smith that bloweth [up] the coals in the fire[works].” – Isaiah 54:6 52 • PERSPECTIVE