Ethnicity and Family - Equality and Human Rights Commission

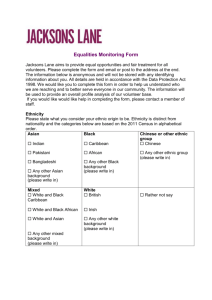

advertisement