Drama (2007) - Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority

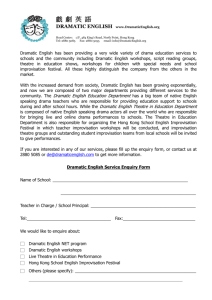

advertisement