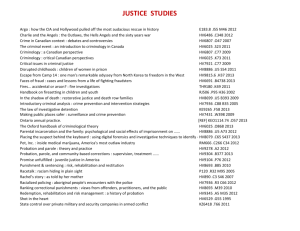

- ASC Division on Critical Criminology

advertisement