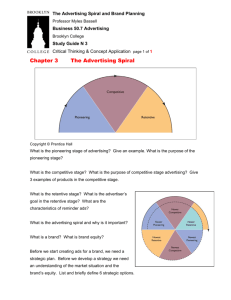

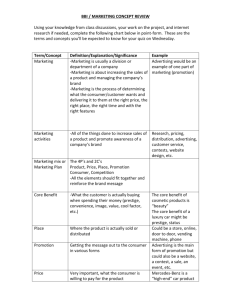

marketing and the internet: a research review

advertisement