Lebanon's Jewelry Sector: Success Story, Locally and Abroad

Lebanon’s Jewelry Sector: Success Story, Locally and

Abroad

BLOMINVEST

BANK

Lebanon’s Main Exports in 2011

May 12, 2012

Contact Information

Research Department research@blominvestbank.com

Head of Research: Marwan Mikhael marwan.mikhael@blominvestbank.com

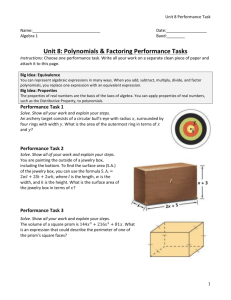

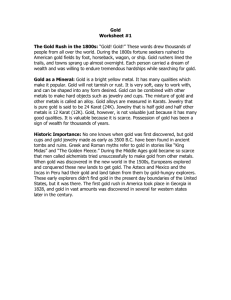

Timeline of Key Events in the Development of the Lebanese Jewelry Industry

Jewelry industry limited to traditional gold pieces

1950

Syrian government’s nationalization of all industries

2007

Acceleration of the rise in gold price

High-end jewelry became more expensive Syrians jewelers relocated to Lebanon

2005

Assassination of former

Prime Minister Rafik Hariri

Buyers were less confident about the economy and more careful with their spending

1900

Ottoman Empire assault on

Armenia

Armenians immigrate to

Lebanon and brought in the know-how of jewelry making

1975

Eruption of civil war

People of talent and aptitude flee the country

2006

2011

Eruption of Arab

Spring

Arab tourists decline

2008

Series of political assassination and prevailing political instability

Dear Readers,

The following Focus in Brief is a two-part study covering the Lebanese jewelry industry. Please find below the first part, the second one will be published in next week's Brief.

Economic Spot

The economy of Lebanon owes a part of its growth to the thriving jewelry industry which has long sustained its stance as the country’s primary exporter. While the recent eco-political developments, from the eruption of the Arab Spring to rising gold prices, brought in a disturbing element to the flourishing sector, the jewelry industry preserves its position as Lebanon’s number one export sector, capturing 35% of the country’s total exports in 2011. In value terms, the share matches an amount of $1.5 billion, far ahead of other industries’ contribution, and trailed distantly by base metals and articles of base metal which had an exported value of $525 million in 2011, the equivalent of 12% of total exports.

Lebanon’s Jewelry Sector: Success Story, Locally and Abroad S A L

A History of Beauty

The history of jewelry in Lebanon has gained the industry the reputation of the leading hub of the

Middle East, challenging that of international centers such as Switzerland, South Africa, and

Russia. The development of the industry was the direct consequence of the Ottoman Empire’s assault on Armenia, pushing Armenians, known for their craftsmanship, to move around 1900 to

Lebanon and bring along the skills of jewelry making. The sector grew further in the 1950s, once again driven by an external shock caused by the Syrian government’s nationalization of all industries. Syrian jewelers relocated to Lebanon, providing additional prosperity to the already growing industry.

But the eruption of civil war in 1975 was a turning point. It triggered a brain drain, driving people of talent and aptitude to flee the country. The war has also snatched Lebanon its stance as a major player on the international scene for the gold trade. “Its position was comparable to that of

Dubai today”, highlights Berge Arabian, member of the Swiss Business Council in Lebanon 1 . The industry has been further affected since 2005 with the assassination of former Prime Minister

Rafik Hariri and the political instability that remains prevalent until today.

The Market’s Landscape

Closed

The Lebanese jewelry industry is a much closed, big, and unregulated market. The accurate size of the sector remains in the unknown with the absence of transparency, and the high level of confidentiality companies in the industry preserve. The existing opacity has long been persistent, perceived as the ultimate way for tax avoidance. Under the Lebanese law introduced in 2004 by late Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri in agreement with the jewelry syndicate, jewelers pay a 10% tax on net profits for jewelry, but are not subject to imported tax on raw material or unfinished products 2 , including metals such as gold, pearls, and stones. Imported finished Jewelry products 3 , embracing the spectrum of international Jewelry brands sold locally, are subject to a

25% tax out of the product cost in addition to Value Added Tax (VAT). When sold locally, products are imposed a 10% VAT charged on the profit margin 4 , paid by the jeweler, not the buyer. While

Lebanon does not impose tax on exported jewelry, when exported, the taxation varies according to the customs or excises levied by the country of destination. Products exported to the States are sold tax free. In Europe, the only imposed tax is the VAT. The Arab world charges different taxes depending on the country’s specific law and whether the brand has been registered there or not. The average regional tax is around 5%. Under the secrecy scheme, it is believed that around

90% of sales are not declared, as claimed off the record by one jeweler 5 .

Another motive behind the high level of secrecy is the sector’s domination by family-run companies, the leaders of which have been operating for at least 5 decades, among which,

Tabbah, Mouawad, Bongia, and Mouzannar. The significant heritage built by the latter and the sensitivity derived from the substantial level of competition and the easiness of imitation or ideas stealing between high-end jewelers strengthen the closed nature of the sector.

1 As appeared in Executive Magazine’s article, “Lebanon - The Orient’s Goldsmith”, issued in January 2009

2 An unfinished jewelry product is one that has not been brought to the final stage of production. It could consist of raw material, including metals such as gold, pearls, or diamond.

3 A finish product is a product that has been perfected, brought to the desired final stage, and ready for sale.

4 The profit margin has been determined in agreement with the jewelers syndicate at 8% for jewelry and 12% for jewelry with precious stones

5 As appeared in Executive Magazine’s article, “Secrets of the Stones”, issued in February 2010

2

Lebanon’s Jewelry Sector: Success Story, Locally and Abroad S A L

The shut door of the industry is also identified as an ideal approach to illegal dealings. Lebanon was reestablished in 2007 into the Kimberly Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) after it was removed in 2004. The aim of the organization is to halt trade of conflict diamonds 6 , and it does so by imposing restrictions on member countries to certify shipments of rough diamonds. Lebanon was dropped earlier for failing to abide by the standards, the consequence of which prevented the country from trading rough diamonds with other KPCS countries, which account for 99.8% of global rough diamond production. Despite its reintegration into KPCS, Lebanon is still considered

“a major diamond laundering route”, and this assumption relies on heavy ground: “An estimated

60% of the West African countries’ diamonds leave destined for Lebanon, yet they are exported at less than 10% of their actual value by being certified as “industrial” rather than “gem-stones” 7 , and then leave Lebanon at about 36 times their imported value”, as noted by Partnership Africa

Canada’s “Diamonds and Human Security Annual Review 2009” 8 .

Big

Estimations of the size of the jewelry market hence suffer from a lack of comprehensive information and are therefore ineffective at projecting the true value generated by the industry.

But what is certain is the substantial contribution of the sector to the economy. Patrick El Khoury, head of publishing and events at Arabian Watches and Jewelry Magazine, asserted he had heard rumors that the sector is worth $4.5 billion, the equivalent of 16% of Lebanon’s GDP in 2010. Yet again, the figure remains a guestimate.

The Lebanese jewelry market provides products ranging from fashion or costume jewelry , that tend to be the most affordable of all jewelry made of less expensive metals and stones as glass, plastic and other synthetics; to high-end jewelry. The later comprises fine jewelry , generally thought of as jewelry that uses at least 14 carat (ct.) gold or other precious metals and precious gems like diamonds, sapphires, rubies or emeralds.

Fine jewelry can be mass-produced or artisan-made one-of-a-kind pieces or limited-edition. Cartier Jewelry is a model of a classic fine jeweler. The other type of high-end jewelry is designer jewelry , more affordable than fine jewelry , and bridges the gap between the latter and fashion jewelry . It could be made with sterling silver, vermeil and gold-filled metals and semi-precious stones such as amethyst, citrine, turquoise, jade, or fresh water pearls. Lanvin Jewelry fits this category.

Lebanon is witnessing a growing interest from young jewelry designers in designer jewelry . They are also moving away from classic designs, featured by George Hakim’s creations, to more edgy and avant-garde styles, incorporated by Paolo Bongia’s designs 9 .

An example of a young avantgarde designer is Karma El Khalil.

Aside from local private jewelers who own factories and supply the local market solely through their stores 10 (e.g. Mouawad, George Hakim); The Lebanese jewelry embraces local wholesalers, jewelers who own factories and supply in large amounts to different stores in the local or international markets (e.g. Giro group); international jewelers who operate through licensing (e.g.

Antoine Hakim holds the license for Tiffany’s), or their own stores (e.g. Cartier). Other jewelers, such as Sylvie Saliba, offer at their stores international brands rather than their own designs. The presence of international brands on the local market does not however threaten much the business of local jewelers who offer products of a quality that competes with that of international products and at more affordable prices.

6 Conflict diamond “refers to a diamond mined in a war zone and sold to finance an insurgency, invading army's war efforts, or a warlord's activity, usually in Africa where around two-thirds of the world's diamonds are extracted”, Wikipedia

7 “The diamond industry can be separated into two distinct categories: one dealing with gem-grade diamonds and another for industrial-grade diamonds. Industrial diamonds are too badly flawed, irregularly shaped, poorly colored, or small to be of value as gems. They lack the clarity and beauty of a gemstone. Hence they are much less expensive than gemstones and are designated for industrial use, principally as a cutting tool or abrasive”, Wikipedia

8 As appeared in Executive Magazine’s article, “A Devious Trade”, issued in February 2010

9 George Hakim and Paolo Bongia are examples of fine jewelry

10 Internationally, they might operate through licensing or privately owned stores

3

Lebanon’s Jewelry Sector: Success Story, Locally and Abroad S A L

Unregulated

The market is big yet unregulated which means anyone, with the required financing, can establish a position in the industry. The government does not force any prior education or experience for a person to legally become a jeweler. While this creates business opportunities to the country, someone without in-depth knowledge and expertise of precious stones and metals might fall due to an unethical stone trader who, for instance, might sell him or her a synthetic diamond for the price of a real one, as the difference sometimes cannot be detected by naked eye. Nevertheless, the unregulated setting allowed Lebanon to stand out as a leader in jewelry and gold production in the Middle East (excluding Turkey), according to the Syndicate of Expert Goldsmiths and

Jewelers in Lebanon (SEGJL), employing 8,000 people with 2,000 qualified jewelers at around 60 main workshops in 2010. This compares with 20,000 employees in the banking sector. Yet again, the true number is anyone’s guess for an industry that performs under-covered.

Markets of Focus

The small population and the never-ending periods of political instability in Lebanon that curb the potential growth of the industry, drove Lebanese jewelers to turn to the Gulf market where many established themselves through licensing, or privately owned stores. This turned strongly profitable as the customer-base and spending habits abroad are far greater than those of

Lebanon. Hence, the industry grew in a way to become heavily dependent on regional sales, either through exporting or targeting Gulf tourists. Boghos Kurdian, president of the Lebanese

Syndicate of Goldsmith and Jewelers, estimates exports to the Gulf to account for about 50% of total gold sales 11 .

Also, Swiss jewelry brands are importing unfinished products to Lebanon and using the cheaper and highly skilled craftsmanship here to turn them into finished products and export them back to

Switzerland. Estimates for sales of jewelry reveal that 10% of Lebanese jewelry is sold locally while 90% exported and sold abroad.

The eruption of the Arab Spring and rising gold prices have hence toned down the growth of the industry as they resulted in a heavy plunge in the flux of tourists and a drop in Arab spending on luxury at home. This translated into a fall in sales for Lebanese jewelers. But the plunge was more severe on local sales than international sales, impacted by the heavy fall in tourists. Regional markets (excluding Turkey) lack factories to respond to their own demand, hence, exported jewelry, finished and unfinished, continued to grow to fulfill the neighboring markets 12 .

While

Arabs remain the key targeted audience for Lebanese jewelers, the sector leverages partly on international sales in the West, mainly Europe, where leading jewelers, among which Tabbah and

Mouawad, established themselves. Others are trying to enter new markets in the West as a way to escape regional disarray.

11 As appeared in ArabianBusiness.com article, “The Sparkle Dim”, issued in May 2011

12 Reliable data on the amount of jewelry sold is unreported

4

Lebanon’s Jewelry Sector: Success Story, Locally and Abroad S A L

For your Queries:

BLOMINVEST BANK

s.a.l.

Research Department

Verdun, Rashid Karameh Str.

POBOX 11-1540 Riad El Soloh

Beirut 1107 2080 Lebanon

Tel: +961 1 743 300 Ext: 1283 research@blominvestbank.com

Marwan Mikhael, Head of Research marwan.mikhael@blominvestbank.com

+961 1 743 300 Ext: 1234

Disclaimer

This report is published for information purposes only. The information herein has been compiled from, or based upon sources we believe to be reliable, but we do not guarantee or accept responsibility for its completeness or accuracy.

This document should not be construed as a solicitation to take part in any investment, or as constituting any representation or warranty on our part. The consequences of any action taken on the basis of information contained herein are solely the responsibility of the recipient .

5