The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 Events UGRR Final

advertisement

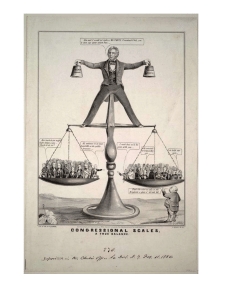

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 © Courtesy of National Archives, Record Group 46; Records of the United States Senate, 1789-­‐1990 The Fugitive Slave Act initially served as a bill intended to quell grievances from northern and southern states following the Mexican-­‐American War. Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas pushed the bill through Congress as a separate set of laws in a series of acts known as the Compromise of 1850. Technically, the act was an amendment to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which southerners felt gave northern states too much leeway when it came to enforcing the return of fugitives. President Millard Fillmore signed the Fugitive Slave Act into law on September 18, 1850. Endangering the 10,000 fugitive slaves living in free states, the act required that all runaway slaves be returned to their masters upon capture. Response to the law in the free states varied from county to county and depended on the abolitionist character of the community. 1 Census figures suggest that more than 10,000 fugitive slaves lived in free states by 1850 (Finkelman 75). Following the Mexican-­‐American War (1846-­‐1848), the issue of slavery proved central to the problem of how to incorporate the ceded territories into the republic. Senator Henry Clay first proposed the Fugitive Slave Act as part of an omnibus bill that was supposed to extend benefits to both northern industrialists and southern slave owners. Congress failed to pass the bill when southerners opposed California’s entry as a free state and northerners opposed the fugitive slave provisions. However, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois drove the single bill’s individual provisions through Congress as separate laws in a series of acts known as the Compromise of 1850. President Millard Fillmore signed the Fugitive Slave Act into law on September 18, 1850. The bill was technically an amendment to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which southerners felt gave northern states too much leeway when it came to enforcing the return of fugitives. The act established several new rules aimed at quelling southern frustration with the 1793 law. Foremost, it stipulated that every county in the United States was required to have commissioners who were responsible for hearing fugitive cases. The commissioner’s only responsibility was to ensure that the purported fugitive was in fact the person described in the slave catcher’s documents. Accused fugitives were not allowed to testify during the hearing, although the law enabled them to have lawyers represent them before the commissioner. One of the most egregious elements of the act dealt with compensation for the county commissioners responsible for reviewing the case: claimants paid commissioners $10 when they ruled in favor of the slave owner, but only $5 if they ruled against. Response to the law in the free states varied from county to county and depended on the abolitionist character of the community. Several high-­‐profile events and legal cases highlighted abolitionist resistance to the law, particularly the 1851 Christiana Riots in Pennsylvania, the 1854 attempted of recapture of fugitive Joshua Glover in Wisconsin, and the murder of a U.S. Marshal in Boston during the trial of fugitive Anthony Burns in 1854. African American leaders (some of whom were themselves fugitives) spoke out vociferously about the law. Many, such as Amy Shadd Cary, Martin Delany, and Henry Bibb, argued that African Americans should flee the United States for Canada, where slavery was outlawed. Between 1850 and 1860, northern commissioners returned 366 individuals to claimants. Although this was far larger than the number returned to owners between 1793 and 1850, it was probably only a fraction of the number of runaways who actually escaped to the free states and Canada between 1850 and 1863 (Finkelman 75). 2 Works Cited & Further Reading “Fugitive Slave Law of 1850,” in Paul Finkelman, ed. Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-­‐First Century. Vol. II. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. Campbell, Stanley W. The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-­‐1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970. 3