velocity series discussion paper 4: factors

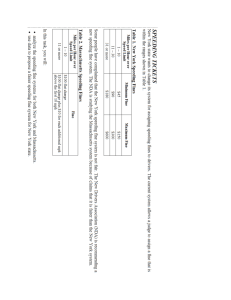

advertisement