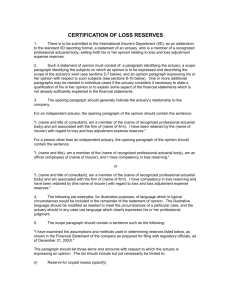

SOP Part 1000 General Red

advertisement