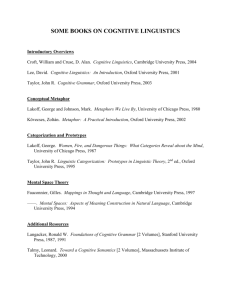

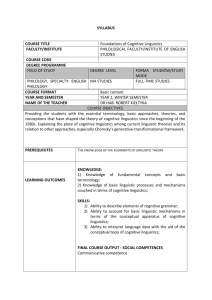

The Cognitive Linguistics Enterprise: An Overview

advertisement