Quantum Bhangra

advertisement

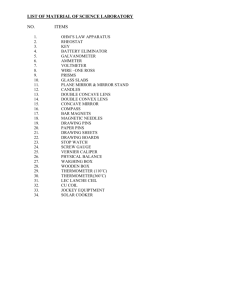

Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma Highly Commended Quantum Bhangra: Bhangra Music and Identity in the South Asian Diaspora Sandeep K. Varma This essay explores the transnational musical form of bhangra and its impact upon South Asian identity within the ‘new’ global diaspora of second and third generation South Asians. Bhangra, originally a form of folk music, has been taken by diasporic South Asians and remixed with various musical styles such as R&B, hip hop, trance, pop, and rap. Recently, bhangra reached the popular culture mainstream through the globally distributed cross-over song ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’ (‘Beware of the Boys’) by UK bhangra artist Punjabi MC. Bhangra music has been simultaneously associated with pop-music icons such as Britney Spears and Madonna, underground South Asian bhangra parties, and commodity culture through advertisements for products as varied as cars, foods, and television programs. While bhangra and its place in the creation of identity has been theorised as following a metaphor of circuitry – a two-way linear model based on a route travelled or an inclusion within a circular group – the complications and multi-layered simultaneity inherent in bhangra as a cultural form demands a more complex framework. This essay examines bhangra and uses the deterritorialising, non-linear, supra-temporal metaphors of quantum mechanics to provide a new theoretical direction for the understanding of bhangra. ‘Balle, Balle’ ‘Balle, Balle’ resounds the thrilling cheer, hands waving in the air. The Punjabi-Canadian boy shakes his head; the weight of his turban adds emphasis to his motion. ‘Balle, Balle’ amidst tears of joy as cousins, aunties, and uncles celebrate a wedding in Southall, England. ‘Balle, Balle’ echoes in the nightclub in Sydney. ‘Balle, Balle’ fails to be translated on MTV’s closed captioning of the new Punjabi MC video1, leaving the children in Illinois to ponder the Punjabi lyrics as they listen, and later as they dance. ‘Balle, Balle’ has no direct meaning in English, but to me and millions of other diasporic South Asians, the performative phrase, the emotive equivalent of ‘yee-haw’, connects us to the transnational musical form called bhangra. The dhol drum beats, two sticks resonating to match the overlain synthesised hip hop. Bhangra’s traditional drum is the background for spoken reggae rhymes, forms fused together to sell Peugeot cars globally.2 The dhol echoes in the halls of George Washington University in anticipation of the eleventh annual Bhangra Blowout National Dance Competition. Computer speakers simulate dhol beats downloaded from the internet. And, in South Asia, farmers dust off their dhols to celebrate the new plentiful harvest, a wedding, or a religious festival. Through the invisible airwaves and into the musical unconscious, the dhol helps create the shout of ‘balle, balle’, that reaches the ears of the local, the hearts of the personal. It takes me ‘home’. The syncretic dhol also infuses the global bhangra wave; it is strength and unity, pleasure, pain, and politics.3 The curved sticks and casing of the dhol echo with bhangra, and in doing so, create a musical form which crafts the cultural identity of ‘South Asians’ as complex, simultaneous, and ultimately diasporic. 17 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma Bhangra is in the Blood What is bhangra? Simply and historically, bhangra is a traditional folk music from the region of Punjab, a lush valley situated between India and Pakistan, two countries in the subcontinental group now problematically generalised and termed ‘South Asia’. Punjab is one of the most fertile regions in the area, and remains a place where bhangra is still commonly used in harvest celebrations, weddings, and religious festivals.4 This ‘folk’ background gives bhangra an authenticity, a cultural origin in whose terms its representations are often framed.5 Most bhangra is sung in the Punjabi language, a Sanskrit-based cousin of Hindi and Urdu, which are the national languages of India and Pakistan respectively. Punjabi also serves as the official language of the Sikh religion. Brightly-costumed dancers wearing turbans, as mandated by Sikhism, and loincloths, called lungis, continue to be the traditional image of bhangra. Bhangra can fall into a framework that represents and recreates the divides inherent in Indian and South Asian regional socio-political relations. In India, a state/territory is often a religious, linguistic, and culinary boundary. For example, Gujarati can refer to a diasporic people, a statehood (of Gujarat), a language, a type of food, music, or a visual aesthetic. In bhangra music, popular South Asian culture is reproduced within the dominant Punjabi/north Indian paradigm, as it is with exported ‘Indian’ food such as the generic curry and tandoori chicken. These constructs, premised on a simplistic colonialist understanding of ‘South Asia’, ignore not only regional and state subjectivities, but also fail to acknowledge complex identities based on transnational cross-pollination. As the Punjabis were displaced, bhangra followed them around the world – first throughout the Commonwealth in the ‘old’ (exclusive) diaspora during the British Raj and the turn of the twentieth century, and then worldwide from the 1960s onward in what Vijay Mishra calls ‘a new diaspora of late capital (diaspora of the border)’, whose defining characteristic is mobility.6 Following this trajectory, bhangra has gained emblematic public status as an element of the Punjabi ‘ethnoscape’, the disjunctive movement of people and workers in a ‘global cultural flow’.7 Although Punjabi is a minor player when placed in the hierarchy of world languages, bhangra has retained its Punjabi lyrics, and more prominently, its characteristic syncopated rhythmic cycle and the presence of the dhol drum.8 These ‘folk’ characteristics of bhangra have also become part of a modern ‘Trans-Asian/Translasian’ of bhangra into fusion forms which resist new diasporic nostalgia.9 Amateur bhangra bands have been performing at weddings and other social occasions in Punjabi communities, such as that in London, since the 1960s, reproducing bhangra and creating new forms through improvisation.10 Expanding beyond the Punjabi diaspora, bhangra has come to represent the ‘South Asian’ diaspora as a whole, since the constructed term ‘South Asian’ has been applied to all people with ethnic, religious, or cultural heritage emanating from anywhere in the south Asian region – which includes the nations of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Afghanistan. ‘South Asian’ attempted to advance identity beyond simply an Asian or Indo-centric focus, but the term may be too expansive, failing to represent subtleties of identity. The grouping ‘South Asian’ as a geographical reference has no nation or religion in its root meaning, and constructs a highly provisional language, a kind of theory in itself, for ‘thinking about how people see themselves as part of broader social formations’.11 The ‘South Asians’ have spread from their homelands throughout the globe, establishing a presence in nations such as the United States, Britain, Australia, Canada, Fiji, Singapore, and Kenya, among many others.12 In each of these locations, new diasporic identities have been imagined and created. In each of these locations, bhangra plays in homes, at parties, in clubs, at charitable benefits, and at festivals.13 In each of these locations, it is important to consider whether bhangra means the same thing to all South Asian people, with their multifaceted and disparate South Asian backgrounds. Today, it is not only the cross-pollinated, hyphenated identities of the South Asian diaspora, but more importantly of their second- and third-generational offspring, who are reappropriating and creating the cultural forms into which bhangra has evolved.14 As these ‘new diasporic’ generations – who are not technically ‘displaced’ – struggle to ‘possess the hyphen’ of their identities, they metaphorically carry bhangra in their blood; in their inherited diasporic longing for the sacred earth 18 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma of their ‘homelands’. Simultaneously, they long to move beyond such essentialist and simplistic teleologies of identity.15 To fit the Punjabi-Indian-American-Hindu identity, for example, together with a Punjabi-Pakistani-American-Sikh, a Gujarati-Indian-American-Christian, and a Tamil-Sri Lankan-American-atheist under the umbrella of ‘South Asian-American’ leaves identity spread thin between many hyphens. As a cultural form, new bhangra creations – what some call post-bhangra or the bhangra-remix – stretch across the hyphens.16 These modern transformations of bhangra also exist in the transnational hyphenated space between such groups as South Asian-Americans, South Asian-Australians, and South Asian-Britons concurrently, as bhangra music is created and heavily consumed in each of these countries.17 Each of those hyphenated spaces brings its own polity, its own complex and competing ideas of civil order and political organisation, and as such bhangra cannot be owned by one hyphenated identity more than another. In this examination of bhangra, the terminology ‘South Asian’ will be used for lack of a better descriptor, but an attempt will be made to retain awareness of the term’s inherent discrepancies and generalisations. Segue – TimeOut South Asian Special Segue (v.) – to proceed to what follows without pause. Used as a direction in music. Act 2 – On Broadway, New York City. There is pride in seeing the poster. There is talk amongst parents. Tickets and cast soundtracks are purchased. At long last, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s newest musical Bombay Dreams has arrived in New York, fresh from its opening run in London. The bhangra-obsessed mark their calendars, eager for new Bollywood-bhangra dance moves on stage. Conservative theatre elitists drool fixatedly, absorbing the erotic, revelling in the hallmarks of South Asian culture, its grandeur and mystique. (Or so we tell ourselves, to bolster our cultural self-importance at this moment of high recognition.) Posters of Bombay Dreams line the streets. Today New York, tomorrow … We are revitalised, and so is the public interest in all things ‘South Asian’. Sunaina Maira’s ‘Indochic’ aptly characterised this phenomenon of popularisation, consumption, commodification, and cultural citizenship, but it now stands that Indo-chic must be updated and replaced by ‘South Asianchic’.18 And nowhere else is this so evident as in the ‘obsessive guide to impulsive entertainment’, the New York TimeOut magazine. The weekly issue of TimeOut for 25 March 2004 featured a ‘Bollywood on Broadway’ tagline on the cover and hinted at the ‘14-Page South Asian New York Special’ inside.19 From screen to stage, theatre to kitchen, and home-studio to popular club, South Asian-chic is clearly a vibrant subculture in New York City. From the Broadway Theatre where Bombay Dreams is performed, you can see Times Square and MTV headquarters. In the MTV building a VJ (video-DJ) hosts the chart countdown, Total Request Live, and once again, Punjabi MC’s crossover bhangra/hip hop hit song, ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’ (‘Beware of the Boys’) receives a top ten spot in the order.20 Later that night at a ‘Basement Bhangra’ party, the song roars the crowd to life – ‘Balle, Balle’ they shout in celebration.21 The Bhangra Remix In the politics of second-generational South Asian identity, mainstream adoption of South Asian culture is seen as both a commodification and a validation.22 Within this framework, bhangra’s major form has become the remix; a diluted and arguably less ‘authentic’ or ‘traditional’ form of South Asian representation. Bhangra in its popular understanding is now a hybrid of borrowed musical traditions, just as second-generational South Asians create hybrid identities and borrow from multiple cultures, traditions, and nationalities in their creative expressions. This is a hybridity akin to Homi Bhabha’s notion of hybridity, one that opens up a ‘third space’ of possibility.23 The bhangra remix has only recently gained mainstream distribution, most notably through Punjabi MC’s ‘crossover’ song ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’, which featured the star rapper Jay-Z. With the ‘help’ 19 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma of Jay-Z, the British Punjabi MC was able to meet the standard of black ‘cool’ and penetrate the US market.24 Although Punjabi MC’s success was celebrated by South Asians around the world, his music’s ‘authenticity’ as a South Asian form was based on its connection to rap music, which is itself often represented by the recording industry as ‘authentic’ black culture.25 One half of the remix partnership seems to outweigh the other. The longstanding history of bhangra’s failure to achieve mainstream recognition may continue despite this ‘breakthrough’ because in the remix, South Asian culture is not acknowledged as wholly legitimate. It achieves legitimacy only when translated through the familiar, marketable, and commodified prism of hip hop. In many of the same ways as hip hop has, bhangra music has taken on characteristics of cultural commodity. The popular soundtrack for the British-South Asian, second-generational ‘crossover’ film Bend It Like Beckham contains heavy bhangra sampling, and ties bhangra to soccer and celebrity.26 Bhangra ring-tones can be downloaded to mobile phones, and bhangra dolls are bought, sold, and collected on eBay.27 Punjabi MC even received an MTV Europe award for Best Dance Act in 2003.28 In Britain and Australia, bhangra dance classes are now being taught in place of more established aerobic routines.29 A recent song by the group Bhangra Knights was used in a highly successful advertising campaign for Peugeot automobiles.30 The advertisement became so popular that the full song from Bhangra Knights was listed as one of the most popular songs in Britain, and ranked highly on popular music charts across the world.31 Although second- and later-generation South Asians – specifically those interested in bhangra – are the primary consumers of these products, the various bhangra forms are easily available to wider audiences. For many of those audiences, bhangra can be seen as partly representing the same homogenised cultural values as other popular musical forms such as hip hop: values such as materialism, sexism, temporality and the supremacy of sex.32 A fuller understanding of bhangra and hip hop musical forms in the context of South Asian identity should move beyond this reductive understanding, yet must also acknowledge the existence of commercial and traditional values. The parallel rise and commodification of distinctive musical or remixed forms premised on bhangra is a marked change from the previous relationship of South Asian music and the West. Bhangra and the bhangra remix do not represent an Orientalism borrowed from the East, or a form of World Music ‘racialised’ to allow non-American and non-European music into the popular market, but instead call to attention a new beyond-hybrid musical creation; a Western musical form based on South Asian imagery, musical rhythms, and traditions initiated by the worldwide diasporic South Asian wave.33 A popular bhangra remix which can serve as an insightful example is the remix of Craig David’s song ‘Spanish’, featuring Rishi Rich.34 Both of these artists are British. As typical of the ‘diasporic intimacy’ of many polycultural bhangra or ‘British Bhangra’ remixes, Craig David is ‘urban black British’ and Rishi Rich hails from a second-generational ‘British-South Asian’ background.35 Even the names used by bhangra DJs construct a complex simultaneous and hybridised identity. Take, for example, the name Rishi Rich. A rishi is an ascetic sage who in the final stages of the Hindu lifecycle renounces the world and all material possessions. In contrast, rich of course refers to material wealth and prosperity, characteristic of the music, videos, and image of Rishi Rich’s namesake; a rapper Richie Rich from Oakland, California.36 Rishi Rich is also popular for his work on the bhangra remix of Britney Spears’ song ‘Me Against the Music’, which contains a bhangra beat but no Punjabi lyrics or mentions of ‘balle, balle’.37 Craig David, the other half of the ‘remix’, is also a popular figure, recently listed at forty-two on a list of 100 Great Black Britons.38 In his original version of ‘Spanish’, Craig David sings of a ‘halfblack and half-Oriental’ ‘señorita’ and sings a verse in Spanish. In the second verse of the Rishi Rich remix, he first asks for a ‘tumbi’, a traditional Punjabi stringed instrument which produces bhangra’s distinctive high tone, and lays a typical bhangra syncopated beat, which stresses a normally weak beat. David’s female target becomes a ‘half-Hindu and half-Punjabi’ ‘señorita’ in a ‘sari’. Instead of knowing ‘a few lines’ of Spanish, Craig David’s remix implies he has become familiar with ‘a few 20 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma lines’ of ‘Punjabi’, which sets the stage for Rishi Rich’s Punjabi verse and replaces the only actual Spanish in ‘Spanish’. Not only does this remix reproduce the hypermasculinity inherent in much of hip hop music, it also reproduces the patriarchal bias ingrained in bhangra and bhangra’s spread as the dominant Punjabi musical form. Both Punjabi MC’s ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’ (‘Beware of the Boys’) and Craig David’s ‘Spanish’ remix represent a male perspective, in which ‘the boys’ are concerned conquering with ‘this female’ and her image. The English lyrics mirror the Punjabi lyrics in their lack of a female voice, as bhangra is traditionally a male form. The dancers and singers of bhangra were originally all male; there existed a parallel female form of music and dance called gidda. Today gidda has not vanished, but is no closer to achieving the mainstream recognition of bhangra despite its similarly catchy, syncopated rhythm, festive sound, traditional origins, and colourful costumes.39 Finally, the ‘Spanish’ remix implies an equivalence of ‘half-black, half-Oriental’ with ‘halfHindu and half-Punjabi’ which is clearly problematic. In this exoticising of the other, akin to Said’s notion of ‘Orientalism’, the ‘Asian’ mystique is a sign of ultimate attractiveness, fascination, and fetishisation.40 ‘Half-Oriental’ in this construction is not a partial identity, but a more important aspect than the commonplace ‘black’ of the singer Craig David. Somehow the forgotten Spanish ‘half’ of the ‘senorita’ creates a sum greater than two halves. The same is true of a ‘half-Hindu and halfPunjabi’ identity. While ‘Oriental’ and ‘black’ imply racial identities, ‘Punjabi’ also implies language and authentic ‘folk’ culture. Issues of national identity are left out of the picture, perhaps assumed to be British, like the singer. However, ‘Spanish’ is tied to the global music commodity market and has spread transnationally to audiences who apply their own meaning where interpretive space exists. Furthermore, the ‘half-Hindu’ identity brings in issues of religious identity and begs the question, how one can be ‘half’ of any religion, when most religions demand complete faith and allegiance to their principles alone? If a ‘half-Hindu’ identity exists, then what fills the other half of the religious space? The bhangra remix form clearly leaves gaping (w)holes in identity formation, and can allow for oversimplification of the struggles of identity to basic binaries. But this tendency must be resisted, and calls for a theory of South Asian identity to fill in the ambiguous spaces in the complicated diasporic South Asian existence of the second and later generations. Brothers and Sisters of Bhangra Bhangra permeates my family. In a Los Angeles childhood, at home and through birthdays, sweet sixteens, twenty-firsts, weddings, and graduations my brother, sister, and I learned the intricacies of the ‘balle, balle’ head-shake. Though often preferring Bollywood movies and filmic Hindi songs, my parents teach us the legacy of our blood, of their homeland. My father’s parents still live in Punjab. My mother’s now live in the neighbouring Indian state of Rajasthan. When we visit our cousins, we exchange mp3s of the latest bhangra music from our respective homes. Indian bhangra. US bhangra. Fusion bhangra. We are Punjabi, though we mostly speak Hindi. We are Hindu, though we have many Sikh friends. My two siblings and I all attended a Catholic high school. We are American, born and raised. We share brown skin. Bhangra unites my family simultaneously, years later. In Australia, I find Karma, a bi-weekly South Asian party with heavy bhangra sampling, similar to the New York desi club scene.41 I find first and second generation desis in Melbourne at Karma. Waves of bhangra reach my ears. I dance. My brother finds a South Asian party in Germany, as he lives the adventures of a traveller. He explores, communicating understanding with motion. He nods his head. He dances. My sister, attending university in Los Angeles, joins one of the many bhangra teams the school has to offer. She practises for hours each day. She wears colourful costumes and her male partner wears an ornamental turban. On a stage at the latest interstate competition, she waits for the curtain to rise. The overflowing audience watches. She dances. 21 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma Bhangra Circuitry Circuit (n.) – a usually circular line encompassing an area or the space enclosed within such a line; a route travelled; the complete path of an electric current including usually the source of electric energy; a two-way communication path between points (as in a computer); an association of similar groups.42 Fuse (n.) – A safety device that protects an electric circuit from excessive current, consisting of or containing a metal element that melts when current exceeds a specific amperage, thereby opening the circuit.43 Fuse (v.) – to blend thoroughly by or as if by melting together, combine.44 The confusion of the bhangra remix due to its identity gaps is assisted by current cultural theories. A number of theories concerning bhangra music have focused primarily upon what is hereafter termed a circuitry-based model; one premised on identity as a fusion; a circuit as a route travelled or a piece of technology with limited capacity; linear, consisting of two end points, with a start and a finish. A circuit and circuitry-based theories of bhangra and South Asian identity often construct identity as a fusion between opposites: bhangra is a mixing or a clash between Western and Eastern, between South Asian and English (substitute for latter Canadian, American, Australian, etc), between authentic and diluted culture, between two halves, between male dominance and female exclusion. These fall into the binary opposition within a circuit’s two poles; a circular line encompassing an area, a cultural space.45 Bhangra is defined by its historical progression, a circuit as defined by a route travelled; the diasporic movement of bhangra from the homeland to the hostlands mirrors the path of energy in a circuit from its energy source.46 Bhangra/hip hop remixes have the ability to reinforce and inform nationalistic and racial identities or ignore them altogether. According to the circuitry model, remixes can be divorced into separate but equal cultural parts – one South Asian, one other – within a bhangra circuit, an association of similar groups around the world, a limited ‘diaspora Punjab’.47 Bhangra is wrongly seen as a circuit in the classic sense; a two-way communications path between binary poles of old and new diasporic generations. To define bhangra simply as existing with the circuitry framework only highlights the limitations of the circuit metaphor. Circuitry is contingent on two-way communications, linear frameworks, and circular pathways within electrical wires separated by entrance or logic gates, limited to either being open or closed. Circuits are limited by a fuse; a regulator which cannot handle currents that are too strong. If too much strong current enters a circuit the fuse melts and a fusion of all the elements occurs, just as in bhangra circuitry models where second-generation South Asian identity, as related to bhangra, is described as fusion. However, when identities become complex, when the currents are too many, or too overlapping, circuits become fused and break down. Fusion models premised on circuitry are a melted, mixed puddle of identity, inseparable from the often distinct, fully-formed, individual diasporic identities that co-exist in the same space. Today, in the globalised, hyperlinked, transnational information age, circuitry technology is shrinking more and more rapidly as it approaches a physical limit beyond which it cannot become smaller. Two-way communication must make way for more expansive theories, allowing multiple forms of interaction beyond binary relations, beyond the static notions of time and space implied in classical circuitry. Cultural studies theories of bhangra music must also follow this trend. As the science of circuitry has advanced, cultural metaphors have failed to follow suit. There must be a response to the call to ‘propose a discourse which challenges the stultifying binarisms that have hitherto pincered the sensibilities of the modern world.’48 We must move beyond the circuit, beyond the hyphen, to a more complex understanding of South Asian identity as expressed through bhangra. As Virinder Kalra writes, ‘often bhangra is used as an excuse to repeat the worn-out pathology of “cultural conflict”, “intergenerational malaise”, 22 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma and “caught between two cultures”’.49 To move beyond this conceptualisation of bhangra, ‘transasian’, transcultural, and transnational alliances incorporating bhangra must not be seen as existing in separate spatio-temporal spheres.50 These forms of identity are constantly and simultaneously influencing, changing, affecting, negotiating, completing, and competing with each other. In the end, there needs to be a theory of South Asian identity which transcends the old binaries of essentialism and simple hybridity and yet still incorporates the complex cultural forms of bhangra.51 Excelsior It seems time to unlearn the ABCDs – short for American Born Confused Desi, an appellation used in South Asian circles to describe second-genners who are perplexed about where their cultural roots lie. The term’s fallacy is its implication that being a ‘hybrid’ or ‘hyphenated’ person is about being half-and-half. For the new fusing generation, it’s more about doubling: identifying fully with more than one place or culture. That means revamped vocabulary, music, cuisine and more. ABCDs? More like American-Born Creative Desis. That neither-here-nor-there space between cultures is at last a You Are Here. Tanuja Desai Hidier52 Quantum Bhangra South Asians, as a diaspora, are characterised similarly to other diasporic groups in terms of movement. ‘Diaspora, by definition, is dispersion, which effectively compresses time and space such that it enables the experiences of many places at what would appear to be one moment’.53 Identity, while based on a locality, a ‘you are here’ version of ‘home’, is also simultaneous, existing in more than one place. Second generation South Asians feel this simultaneity on a more complex and subtle level: as they have no direct memories of dispersion, they have no ‘imaginary homeland’ to imagine.54 Nikos Papastergiadis’ appropriation of the concept of deterritorialisation, of belonging to multiple communities without common territory, would seem to offer a theoretical alternative with which to consider the second generation South Asian bhangra identity.55 However, despite movement towards a more expansive framework, Papastergiadis still relies on Rouse’s ‘alternate cartography of social space’ based on the notions of ‘the circuit’ and ‘the border’. His weight upon ‘the process of being in a circuit’, and his reliance upon ‘circuits as spaces for community’ does not open a vast enough theoretical space.56 ‘The circuit that feeds musical forms often bypasses the metropolitan and commercial music networks’ as Papastergiardis argues, but the flow of bhangra simultaneously includes them in a significant way.57 The circuit metaphor is not expansive enough to advance the notion of deterritorialisation that aptly highlights cultural forms today. A new framework incorporating deterritorialisation must be proposed that looks beyond the circuit terminology. As the circuitry metaphors of cultural studies must evolve to include new understandings of time and space, current physics is looking for alternatives to the circuit, in this case the tangible form of particle-based circuit technology. Out of an attempt to understand the smallest of particles, in hope of unlocking the secrets of the largest physical phenomena, physicists brought the theory of quantum mechanics into being. While not all scientific metaphors and theories are applicable to cultural dynamics, the metaphors of quantum mechanics provide a new, simultaneous approach to an understanding of particles, waves, time, and space which clearly applies to bhangra. If bhangra acts as a medium for South Asian youth to effectively ‘reinvent their own ethnicity’, then quantum mechanics can provide an accurate framework which reflects the complex realities of this reinvention, and avoids imposing rigid linear or circuitry-based fusion metaphors upon a far more multifaceted cultural form.58 Quantum mechanics, in its simplest understanding, proposes the theory of wave-particle duality. In wave-particle duality, multiple ‘forces’ or ‘waves’ can occupy the same space simultaneously with particles.59 In some instances, quantum mechanics has shown that light can demonstrate 23 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma the properties of both a particle and a wave. The South Asian diaspora, when seen as a wave or waves, exists simultaneously on a transnational level, and yet individual complex identities also concurrently represent locality, held down to a particular place by weight: in physical terms, a particle. Particles are the smallest building blocks of physical reality, as South Asian localities are the most specific forms of a broader wave of the South Asian diaspora. Heisenburg’s uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics shows us that particles cannot be pinpointed, but can only be described in approximations, often simply expressed as where the particle is not, because of the perturbations created by the ‘interaction between observer and object’.60 There is no static origin point to understand, as examination creates movement or instability. Second generation South Asians are without a static cultural origin of time or space, one step further removed than their parents. If examined too closely, their sense of diasporic nostalgia is for an imaginary origin, at best. Their sense of belonging must be re-imagined.61 Second generation South Asians lack a clear teleological structure, something they share with quantum particles. The links between cultural space, stability, and reproduction have been decoupled and made quantum. Tanuja Desai Hidier’s call for a ‘doubling’ in South Asian American identity is a notion that must be expanded to a triple- or even a quadruple-layered concept of identity before it can be applied to all second-generation South Asians.62 A Punjabi-Pakistan-Australian-Sikh living in Canada hears bhangra created by a Gujarati-Indian-British-Hindu. Hyphens cannot be separated into equal parts, only combined into a complex whole which is more than the sum of two halves, and so a melted fusion-identity serves only to overload a circuit, to mix and blend away significant portions of identity. To better explain this level of identity, quantum mechanics again proposes a new, whole, and simultaneous understanding of the interaction between South Asian particles. In quantum ‘superpositioning’, particles carry units of ‘spin’ and can exist in two states at once. In binary terms, a particle can represent 0 and 1 simultaneously.63 South Asians, with a local spin, exist simultaneously as part of a diaspora and part of a homeland cultural nation. What, then, is quantum bhangra? Simultaneity. Multiple layers of identity. The opposite spins of particles which exist in the same space at the same time, while concurrently representing a particle locality and larger waves of identity. It is the multiplicity of bhangra, created by the South Asian artist and exported by the music industry and transnational cultural networks. Quantum bhangra is the sum of the unequal halves of a remix, a superpositioned nationality which cannot be pinned down simply by its motion or location. Quantum bhangra is a place where identity is made up of more than one or two factors fused together. In the end, one final principle of quantum mechanics is applicable to bhangra. A quanta is a portion or particle, a small part, but it is also defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as ‘large’ or ‘significant’.64 It is a fundamental unit of energy, simultaneously incomplete and significant. Quanta, when superpositioned, tend to destabilise the surrounding environment.65 Bhangra’s arrival into the mainstream represents a superpositioned particle entering a new environment. The destabilising effects have allowed bhangra to reach a new level, to impact and challenge definitions in national and transnational surroundings on multiple levels through bhangra’s global spread, again making traditional circuitry definitions outdated. Destabilising, superpositioned quantum bhangra particles have affected their local environments and have also changed the globalised waves for all those touched by the South Asian diaspora. Quantum bhangra is beyond the scope of the counter-hegemony of Homi Bhabha’s ‘hybridity’.66 Destabilising hegemonic flows, being themselves a part of larger waves, simultaneously carry some of the hegemony represented by bhangra’s traditional roots, its music industry distribution and its exclusive Punjabi form. Quantum bhangra occupies the place of quantum mechanics in the construction of reality, citing cultural forms as the building blocks of identity, particles which obey unique rules and through their existence make up the atoms of diasporic consciousness. Quantum bhangra exists in the liminal, in-between space of Bhabha’s ‘third space’ where boundaries dissolve, but it is not only marginally perceptible. It is one of the core structures, a fundamental particle of mainstream South Asian diasporic identity and identification, especially to second and third generation South Asians through the bhangra-remix form. 24 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma Quantum bhangra is also about unity, in an unfixed context. This understanding is furthered by the quantum mechanics metaphor, which allows for the complex multiplicity of wave and particle simultaneity. Identity in a quantum framework is unifying and particular, moving, counterflowing, and isolating all at once. It is ‘both real and metaphorical; at once ‘located’ and contextualised, yet also transgressive … It invites us to make sense of social and political life with reference to the simultaneity and complexity of experience, from the local to the global level.’67 The depth and detail of quantum frameworks as a tool of cultural studies is a vastly uncharted and exceptionally promising area. The implications of these metaphors for South Asian identity and bhangra music will lead to a new and complex engagement with second-generational South Asian identity and with the new and changing forms of bhangra. Ultimately, the unique cultural forms diasporic people create will evolve, and hopefully new cultural metaphors like quantum bhangra will enable cultural studies to accurately map cultural space. Notes 1 Punjabi MC, ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’ (‘Beware of the Boys’), see <http://www.panjabi-mc.com>. ‘Bhangra Knights’ (2004 Television Commercial for Peugeot Automobiles), viewed 4 October 2004, <http:// www.bhangranights.com>, <http://www.bhangraknights.co.uk>. 3 R. Dudrah, ‘Drum’n’dhol: British bhangra music and diasporic South Asian identity formation’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 5, no. 3, 2002, p.374. 4 ‘Bhangra: Vibrant Energy’, India Journal (Special Baisakhi Issue), 16 April 2004, pp.C14, C18. 5 S. Banerji, ‘Bhazals to Bhangra in Great Britain’, Popular Music, vol. 7, no. 2, 1988, p.212; G. Farrell, Indian Music and the West, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1997, p.211. 6 V. Mishra, ‘The Diasporic Imaginary: Theorizing Indian Diaspora’, Textual Practice, vol. 10, no. 3, 1996, p.422; S. Shukla, ‘Locations for South Asian Diasporas’, Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 30, 2001, pp.551-572. 7 A. Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, University of Minneapolis Press, Minneapolis & London, 1996, pp.48-65. 8 Banerji, p.212; Farrell, p.211; V. S. Kalra, ‘Vilayei Rhythms: Beyond Bhangra’s Emblematic Status to a Translation of Lyrical Texts’, Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 13, no. 3, 2000, pp.82. 9 R. Kaur & V. Kalra, ‘New Paths for South Asian Identity and Musical Creativity’, in S. Sharma, J. Hutnyk & A. Sharma (eds), Dis-orienting Rhythms: The Politics of the New Asian Dance Music, Zed Books, London, 1996, pp.217–231. 10 Farrell, p.211; G. Baumann, ‘The Reinvention of Bhangra: Social Change and Aesthetic Shifts in Punjabi Music in Britain’, Journal of the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation, vol. 32, no. 2, p.85. 11 Shukla, p.553. 12 Mishra, pp.421-447 13 S. Pande, ‘Bhangra: Vancouver Style’, Performing Arts and Entertainment in Canada, vol. 3, no. 3, 1999, p.4; Shukla, pp.555559. 14 T. Hidier, ‘Salaam, New York’, TimeOut New York, no. 443 (25 March – 1 April 2004). Available from <http:// www.timoutny.com/features/443/443.sea.html>. 15 Mishra, p.432. 16 Mishra, p.433. 17 Dudrah, pp.363-365; J. Warwick, ‘Make way for the Indian: Bhangra music and South Asian presence in Toronto’, Popular Music and Society, vol. 24, no. 2, 2000, pp.25-45. 18 S. Maira, ‘Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies’, Journal of Asian American Studies, vol. 3, no.3, October 2000, pp.329-369. 19 Hidier. 20 ‘MTV News’, 15 January 2003, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://mtv.co.uk/news/article.jhtml?articleId=30024324>. 21 S. Maira, ‘Desis reprazent: bhangra remix and hip hop in New York City’, Postcolonial Studies: Culture, Politics, Economy, vol. 1, no. 3, 1998, pp.357-371; Hidier. 22 Maira, pp.350, 360. 23 H. K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture, Routledge, London, 1994. 24 Hidier. 25 Maira, p.360. 26 ‘Amazon.com: Music: Bend It Like Beckham [SOUNDTRACK]’, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://www.amazon.com/ exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/B00008DCQJ/102-8920614-6113734?v=glance#product-details>. The review of the Bend It Like 2 25 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma Beckham (2002) soundtrack by Jerry McCulley from Amazon.com described it as ‘world music with a dancefloor beat and a smile’. 27 ‘Oriental Ringtones’, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://ringtone.au.com/ringtones_0_48_oriental---.html>. 28 ‘MTV News’. 29 BBC, ‘Doing the Bhangra beat,’ 5 February 2004, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://www.bbc.co.uk/threecounties/do_ that/2004/02/bhangra_dancing.shtml>. 30 ‘Bhangra Knights’. 31 BBC, ‘Top of the Pops – Bhangra Knights Page 1’, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://www.bbc.co.uk/totp/artists/b/ bhangra_knights/underthegrill/page1.shtml>. 32 S. Deshpande, ‘Grannie Doesn’t Skip a Bhangra Beat’, UNESCO Courier, July 2002, pp.49-51. 33 Farrell; J. Hutnyk, ‘Adorno at Womad: South Asian Crossovers and the Limits of Hybridity-talk’, Postcolonial Studies, vol. 1, no. 3, 1998, pp.401-402. 34 For lyrics, see Craig David, ‘Spanish’ at <http://www.mlyrics.com/lyrics/144116/Craig_David/Spanish>. 35 Dudrah, p.363. 36 Def Jam Music Group, ‘Richie Rich’, Def Jam Artists Profiles, 1998, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://www.defjam.com/ artists/richie/richie.html>. Riche Rich was also the name of a comic book character created by Alfred Harvey in the 1930s who later appeared in a 1980s children’s television show ‘The Riche Rich Show,’ and subsequently in a 1994 film, ‘Richie Rich.’ In each of these renditions, Richie Rich was the richest boy in the world. Presumably, the rap artist derives his name from the comic character. See <http://home.att.net/~thft/richie.htm>. and <http://www.classicmedia.tv/harvey/ characters/richie.html>. 37 ‘Rishi Rich’, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://www.rishirich.com>. 38 Every Generation, ‘100 Great Black Britons’, 2003, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://www.100greatblackbritons.com>., and <http://www.100greatblackbritons.com/bios/craig_david.html>. 39 ‘Bhangra: Vibrant Energy’. 40 E. Said, Orientalism, Routledge & Keegan Paul, London, 1978. 41 Desi – ‘of our land’; often – ‘of our culture’; usually – ‘of South Asia’. 42 ‘Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary’, 2004, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://www.m-w.com/cgi-bin/dictionary>. ‘The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition’, ‘fuse 2’, viewed 1 October 2004, <http: //www.bartleby.com/61/28/F0372800.html>. 43 44 ibid. S. Banerji & G. Baumann, ‘Bhangra 1984–88: Fusion and Professionalization in a Genre of South Asian Dance Music’, in P. Oliver (ed.) Black Music in Britain: Essays on the Afro-Asian Contribution to Popular Music, Open University Press, Milton Keynes, 1990, pp.137–53. 46 Farrell; A. Bennett, ‘Bhangra in Newcastle: Music, Ethnic Identity and the Role of Local Knowledge’, Innovation, vol. 10, no. 1, 1997, pp.107-117. 47 P. Singh & S. Thandi (eds), Globalization and the Region: Explorations in Punjabi Identity, Association for Punjab Studies, Coventry, 1996, p.1. 48 N. Papastergiadis, ‘The Deterritorialization of Culture’ in The Turbulence of Migration, Polity, Cambridge, 2000, p.105. 49 Kalra, p.82. 50 Kaur & Kalra. 51 Papastergiadis, pp.116-117. 52 Hidier. 53 Shukla, p.551. 54 S. Rushdie, Imaginary Homelands, Viking, New York, 1991, p.9. 55 Papastergiadis, pp.100-121. 56 ibid., pp.115-116; R. Rouse, ‘Mexican Migration and the Social Space of Postmodernism’, Diaspora, vol. 1, no.1, 1991, pp.12-14. 57 Papastergiadis, pp.116-117. 58 P. Gilroy, ‘Between Afro-centrism and Euro-centrism: Youth Culture and the Problem of Hybridity’, Young: Nordic Journal of Youth Research, vol 1, no.2, 1993, p.82. 59 J. Jenkins, ‘Some Basic Ideas About Quantum Mechanics’, University of Exeter, Department of Theoretical Physics, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://newton.ex.ac.uk/research/semiconductors/theory/people/jenkins/mbody/mbody2.html>; Encyclopædia Britannica, ‘Quantum Mechanics’, <http://www.brittanica.com/eb/article?tocId=77502>. 60 W. Heisenberg, The Physical Principles of Quantum Theory, Dover Publications, Dover, 1949, p.3. 61 Papastergiadis, p.117. 62 Hidier. 63 ‘Introduction to Quantum Computation’, Centre for Quantum Computer Technology, 2004, viewed 1 October 2004, <http://www.qcaustralia.org/introqc.htm>; G. Johnson, A Shortcut Through Time: The Path to the Quantum Computer, Vintage, London, 2003, pp.5-8. 45 26 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au Limina, Volume 11, 2005 Sandeep K. Varma 64 ‘Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary’. D. Deustch (ed.), The Fabric of Reality, Viking, London, 1997. 66 Bhabha. 67 A. Paolini, ‘Globalization’ in P. Darby (ed.), At the Edge of International Relations: Postcolonialism, Gender, and Dependency, Duke University Press, Durham, 1997, p. 53. 65 27 © The Limina Editorial Collective http://limina.arts.uwa.edu.au