Managing Hazards Syllabus 2015

advertisement

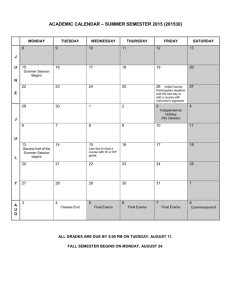

Syllabus IU SPEA in London 2015 COURSE TITLE: Managing Hazards in Europe and the United States I and II FACULTY: Professor John D. Graham and Sameeksha Desai, Indiana University, Professor Ragnar Lofstedt and David Self, King’s College London and Laura Kelly, Department for International Development. Teaching Assistant: David Self CLASSROOM LOCATION: Waterloo Campus, King’s College London, rooms TBA PROGRAM DATES: June 29 – July 19, 2015 (3 week course) June 29 – August 6, 2015 (6 week course) CREDITS: Three or Six V482/V582 course PROGRAM OVERVIEW The purpose of this three or six-­‐credit offering is to examine how hazards are managed through a mixture of lectures, case studies, and classroom discussions. The program is offered in an educational context that invites comparison of how the United States and Europe cope with known or potential hazards to human health, safety and the environment. The intellectual style of the course will be interdisciplinary, with significant reliance on disciplinary contributions from environmental science, public health, public management, non-­‐profit management, policy analysis, political science, economics, and law. This is not a technical course in the methods of risk assessment or risk-­‐benefit analysis. It is a management course. However, some of the lectures and case material will have significant scientific and quantitative content. Pre-­‐course reading requirements include some background on the European Union and some background on risk analysis. There are no course prerequisites. Most undergraduate SPEA students may obtain V482 credit toward their majors – see an academic advisor for details. MPA, MHA, and MSES students in SPEA can earn V582 credit for the course if, in addition to fully participating in the course, they prepare (solo or in pairs) a research paper comparing how the US and the UK manage a particular hazard. 10/13/2014 Page 1 COURSE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Course Goals The overriding course goal is to cultivate the student’s ability to ask insightful questions about risks and decisions related to those risks. A comparison of American and European responses risks will be used periodically to foster questions and discussion. Decisions of interest may be at the level of the individual consumer or worker, the company or labor union, or a responsible governmental entity. The scope of risks to be addressed include those affecting human health, safety and the environment. Specific course goals include: • To understand how risks are identified, quantified and evaluated; • To appreciate the strengths and limitations of different risk-­‐management strategies; • To understand how people form perceptions of risks and how communication affects perceptions and management. Course Objectives Course objectives are defined according to the major chunks of the course: risk assessment, risk perception, risk management and risk communication. Risk Assessment Objectives • Identify the major sources of information about risk, the analytical methods used to quantify risks, the circumstances that motivate use of one method as opposed to another. • Distinguish risks that are uncertain from risks that are known yet variable in a population. • Demonstrate an intuitive appreciation of probabilities, particularly in the case of low-­‐probability, high-­‐consequence events. • Classify the different types of harm or damage that are commonly assessed in formal risk assessments. Risk Perception Objectives • Explain why some risks generate more public concern/anxiety than others. • Illustrate some technologies that have been stigmatized by public concerns about risk. • Compare European and American perceptions of similar risks. Risk Management Objectives • Define the classic analytic frameworks for managing risks. • Explain why zero risk is not usually a feasible or desirable outcome. • Show how the power to manage risk is allocated differently in various regulatory settings. Risk Communication Objectives • Describe how the principles of risk communication were derived from risk-­‐perception research. • Explain why fears of some risks are amplified why other fears are assuaged. • Formulate some management strategies when the lay public and experts seem to disagree about the seriousness of risks. 10/13/2014 Page 2 CLASS SCHEDULE The course will meet each Monday, Tuesday and Thursday (except for week 2, which will run Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday) day during the week from June 29 through August 6, 2015. The morning session will run from 10:00 to 11:30 am. The afternoon session will run from 12:00-­‐1:30 pm and on Tuesdays there is an evening session from 3:00 – 4:30 pm. The formal course sessions will be supplemented by three or five cultural excursions (depending on course length taken -­‐ further details to be announced). GRADES AND EXPECTATIONS A grade will be awarded for each three credit hour course. For the six credit V482/V582 class, grades will be comprised of four exams (40%), the London Risk Project (40%), attendance and class participation (10%), and pop quizzes (10%). For the three credit V482/582 class there will be two exams (40%), the London Risk Project (40%), attendance and class participation (10%), and pop quizzes (10%). Readings must be completed before each class session. Reading assignments are subject to pop quizzes, and familiarity with readings will be reflected in the class participation grade. Exams Four exams (two for 3 credit course) will be administered throughout the course of the summer school (see syllabus). These will be open book exams with a series of questions covering both the lectures and readings set. Further details will be provided during the first week of the school. The London Risk Project This assignment requires the submission of an individual written report (approximately 1000 words for undergraduate students, 2000 words for postgraduate students) and a twenty-­‐minute group presentation on Thursday 16 July (for students taking weeks 1-­‐3), or Thursday 6 August (for students taking weeks 1-­‐6). Students are expected to clearly illustrate the economic, political and social factors that affect the ways in which actors manage and communicate risks. This project allows students to explore risks relevant to their host city, London, and increase their understanding of policy implications within a European context. Student groups will select the risk they intend to investigate, subject to approval by the project supervisor. Further details will be made available on OnCourse. The project supervisor will introduce the project on Tuesday, July 1st. The due date for the written report is 10:00 am on Thursday 16 July for students taking weeks 1-­‐3, or 10:00 am on Thursday 6 August for students taking weeks 1-­‐6. 10/13/2014 Page 3 Class Attendance and participation Students are expected to attend all sessions as laid out in the syllabus. Students are also expected to actively participate in class discussions and projects set. Pop Quizzes Pop quizzes will be unannounced 5-­‐minute multiple-­‐choice tests based upon the readings and lectures given. ACADEMIC INTEGRITY As always, no form of academic dishonesty will be tolerated. If your instructors suspect academic dishonesty, you will be notified immediately and asked to explain your actions. If academic dishonesty is proven, you will receive a grade of zero for the particular work in question; repeat offense is ground for failure in the course. If you have questions or concerns on how to properly cite the work of others, please ask for help ahead of time. For more information about academic honesty and plagiarism, see the Indiana University Code of Student Rights, Responsibilities, and Conduct at http://dsa.indiana.edu/Code/index.html. ATTENDANCE AND TARDINESS Attendance and classroom participation is necessary to excel in these courses. A percentage of your final grade will come from both your attendance and how the instructors perceived you participated throughout the courses. Due to the condensed nature of the courses, unexcused absences will not be authorized. Any class work missed during an unexcused absence – including the attendance and class participation grade for that session, exams, and pop quizzes – cannot be made up. Excused absences will be reviewed on a case by case basis. Excused absences require notification beforehand, with a valid reason for missing the class. If the situation warrants, the student will be expected to provide written documentation for an excused absence, such as a doctor’s note. Arrangements should be made with a classmate to take notes and obtain copies of handouts when absence is unavoidable. It is the student’s responsibility to initiate contact with the instructor to make up missed work, such as quizzes or exams. Tardiness is disruptive and should be avoided if at all possible. Repeated tardiness may result in a lower attendance and class participation grade. Attendance at the three course excursions is required and will be included in the attendance and class participation grade. 10/13/2014 Page 4 CLASS SESSIONS, ASSIGNMENTS & READING LIST Week Session Day Date Instructor Topic Monday 1 29-­‐Jun Lofstedt Risk Communication I 10:00 – 11:30 The psychometric perspective on risk perception; attributes of hazards that provoke public concern; public acceptance of risks; accidents as signals; heuristics that influence risk perception; technological stigma; social cascades; alarmism and apathy; an example of how the same risk is perceived differently in the US and the EU. Monday 2 29-­‐Jun Lofstedt Risk Perception 12:00 – 13:30 How the field of risk communication evolved from risk perception research. Tuesday International Risk 3 30-­‐Jun Kelly 10:00 – 11:30 Management Guest lecture by Laura Kelly. Tuesday London Risk Project Intro 1 4 & 5 30-­‐Jun Self 11:30 -­‐ 17:00 and Trip 11:30 – 12:00 Introduction to the London Risk Project 12:00 – 16:00 Trip to the Museum of London (with assignment) 16:00 – 17:00 Debriefing discussion back at Waterloo campus Wednesday 1-­‐Jul: Excursion (no class). Details TBA. Thursday 6 2-­‐Jul Lofstedt Risk Communication II 10:00 – 11:30 Why fears of some hazards are amplified and others suppressed; how predictable biases in personal risk perception can be overcome with communication; the future of risk communication. Thursday 7 2-­‐Jul Lofstedt Trust and post trust 12:00 – 13:30 2 8 Monday 10:00 – 11:30 6-­‐Jul Lofstedt 9 Monday 12:00 – 13:30 6-­‐Jul Lofstedt 7-­‐Jul Lofstedt 7-­‐Jul Lofstedt Lofstedt Commission 7-­‐Jul Self Exam 1 8-­‐Jul Lofstedt Risk vs hazard – how do 10 11 12 13 10/13/2014 Tuesday 10:00 – 11:30 Tuesday 12:00 – 13:30 Tuesday 15:00 – 17:00 Wednesday The pros and cons of deliberation Criticisms of risk perception/communicati on and the future of the discipline The Swedish acrylamide scare Page 5 10:00 – 11:30 we best regulate in the 21st century? In Europe there is an intrinsic debate as to whether one should regulate chemicals based on intrinsic hazard or assessment of risk, or possibly a combination of both. Wednesday Regulating Risks, the US 14 8-­‐Jul Lofstedt 12:00 – 13:30 vs. EU systems How the statutory, administrative and legal setup in the United States influences the way hazards are managed. How the design of the European Union, and the governance of the member states, influence the way hazards are managed. How regulatory trends in the USA and Europe are diverging. Thursday 9-­‐Jul & Friday 10-­‐Jul: Excursion (no class). Details TBA. The changing nature of 15 13-­‐Jul Lofstedt regulatory policy in Europe This session discusses the reasons to why some regulators such as EMA and EFSA are promoting ever increasing transparency regimes with regard to posting declaration of interests of experts, making expert hearings public and sharing clinical trial data. Is the increase of such transparency measures a good thing in terms of public good, and what may be some of the short term and long term consequences of such policies? Monday 16 13-­‐Jul Lofstedt Aspartame 12:00 – 13:30 Introduction to the 2005 scare stipulating that aspartame (an artificial sweetener) could cause cancer in laboratory animals and therefore should be banned. The scare ended following the European Food Safety Authority conducting an independent analysis of the data, which showed that the link could not be proved. Tuesday The use and abuse of the 17 14-­‐Jul Lofstedt 10:00 – 11:30 substitution principle The substitution principle is one of the building blocks of modern day chemical regulation as highlighted in the registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemical regulation (REACH). But what is the substitution principle, what is the history of its use and how do relevant authorities and regulatory actors view it? Tuesday Risk, politics and trade 18 14-­‐Jul Kelly 12:00 – 13:30 disputes Tuesday 19 14-­‐Jul Self Exam 2 15:00 – 17:00 Wednesday 15-­‐Jul: Excursion (no class). Details TBA. Monday 10:00 – 11:30 3 10/13/2014 Page 6 20 Thursday 10:00 – 11:30 16-­‐Jul Lofstedt 21 Thursday 12:00 – 13:30 16-­‐Jul Lofstedt 22 Monday 10:00 – 11:30 23 24 4 Monday 12:00 – 13:30 Tuesday 10:00 – 11:30 20-­‐Jul Desai 20-­‐Jul Desai 21-­‐Jul Desai 25 Tuesday 12:00 – 13:30 21-­‐Jul Desai 26 Tuesday 15:00 – 16:30 21-­‐Jul Desai The siting of difficult projects from BSL-­‐4 facilities to waste incinerators Risk communication and high levels of uncertainty: NASA, space and the Mars sample return programme Globalization at work: US and European trade relations Globalization, risk and FDI Is a regulatory “race to the top” a real thing? How does political instability affect market risk? (I) How does political instability affect market risk? (II) Wednesday 22-­‐Jul: Excursion (no class). Details TBA. 27 Thursday 23-­‐Jul Self 10:00 – 11:30 So what is “risk-­‐based” and who cares? The rise of risk governance in the US & EU The definition of risk-­‐based governance; the history of risk-­‐based governance in the US and EU; the role of risk in public and private sector governance; the drivers and constraints of risk-­‐based governance. From precaution to Thursday 28 23-­‐Jul Self protectionism: The 12:00 – 13:30 global politics of food The definition of risk-­‐based governance; the history of risk-­‐based governance in the US and EU; the role of risk in public and private sector governance; the drivers and constraints of risk-­‐based governance. How do we ensure that both emerging and reemerging risks are highlighted and mitigated within an increasingly complex and globalized system of food trade? 29 5 30 10/13/2014 Monday 10:00 – 11:30 Monday 12:00 – 13:30 27-­‐Jul Graham 27-­‐Jul Graham Risk assessment and the science of safety Risk management methods Page 7 Tuesday 28-­‐Jul Desai 10:00 – 11:30 Tuesday 32 28-­‐Jul Desai 12:00 – 13:30 Tuesday 33 28-­‐Jul Self 15:00 – 17:00 Wednesday 29-­‐Jul: Excursion (no class). Details TBA. Thursday 34 30-­‐Jul Graham 10:00 – 11:30 31 35 30-­‐Jul Monday 10:00 – 11:30 3-­‐Aug Graham Exam 3 Basics of the World Trade Organization Case Study: Genetically-­‐ modified foods at the WTO Case Study: Rare earths at the WTO An army marches on its (healthy) stomach. The Monday 37 3-­‐Aug Self effectiveness of food 12:00 – 13:30 hygiene barometers in the US and EU Food hygiene barometers are publically available scoring systems that inform the public of the level of hygiene within food business operators, such as restaurants and supermarkets. The intended outcome is to ensure food businesses operate with a high level of hygiene otherwise an informed public will buy its produce elsewhere. There have been many attempts within the US and EU to implement these barometers, but are they working? Tuesday Case Study: Poultry at 38 4-­‐Aug Graham 10:00 – 11:30 the WTO Tuesday Case Study: The US and 39 4-­‐Aug Graham 12:00 – 13:30 EU on shale gas Tuesday 40 4-­‐Aug Self Exam 4 15:00 – 17:00 Wednesday US-­‐EU: The Quest for 41 5-­‐Aug Graham 10:00 – 11:30 Regulatory Cooperation Weighing Risk and Wednesday 42 5-­‐Aug Self Benefit: Who Should 12:00 – 13:30 Decide? When determining the optimal balance between risk and benefit, the locus of decision making varies from complete individual choice to complete control by a regulatory body. What are the relative merits of decision-­‐making at different levels? Thursday 43 6-­‐Aug Self Student Presentations 10:00 – 11:30 Thursday 44 6-­‐Aug Self Student Presentations 12:00 – 13:30 36 6 Thursday 12:00 – 13:30 Risk and entrepreneurship Corruption and risk 10/13/2014 Graham Page 8 READING LIST READING ASSIGNMENT PRIOR TO START OF PROGRAM • McCormick, J. (2001). Environmental policy in the European Union (pp. 1-­‐151). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave. Session Reading(s) 1 • Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of risk. Science, 236(4799), 280-­‐285. • Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-­‐1131. 2 • Fischhoff, B. (1995). Risk perception and communication unplugged: Twenty years of progress. Risk Analysis 15(2), 137-­‐145. 3 • Readings TBA 4 & 5 • Mythen, G. (2008). “Sociology and the Art of Risk.” Sociology Compass. 2(1):299-­‐316. 6 • Kasperson, R., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H.S., Emel, J., Gobel, R., et al. (1988). The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8(2), 177-­‐187. • Weinstein, N. D. (1989). Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science, 246(4935), 1232-­‐1233. 7 • Lofstedt, RE. 2008. Risk Management in Post Trust Societies. London: Earthscan. • Porrtinga, W. and N.Pidgeon. 2003. Exploring the dimensionality of trust in risk regulation. Risk Analysis, Vol.23, p. 961-­‐972. • Slovic, P. 1993. Perceived risk, trust and democracy. Risk Analysis, Vol.13, p. 675-­‐682. 8 • Chess, C. and K.Purcell. 2002. Public participation and the environment: Do we know what works? Environment, Science and Technology, Vol. 33, p. 2685-­‐2692. • Lofstedt, RE. 1999. The role of trust in the North Blackforest: An evaluation of a citizen panel project. Risk: Health, Safety and Environment, Vol.7, p.10-­‐30. • Renn, O. et al. 1995. Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation. Dordrecht:Kluwer. 9 • Gigerenzer, G. 2010. Personal reflections on theory and psychology. Theory and Psychology, Vol. 20, p. 733-­‐743. • Lofstedt, RE. 2004. Risk communication and management in the twenty-­‐ first century. International Public Management Journal, Vol.7, p. 335-­‐346. • Lofstedt, RE and A. Boholm. 2008. The study of risk in the 21st century. In Lofstedt and Boholm 2008. • Lofstedt, RE. and L. Frewer. 1998. Introduction. In Lofstedt RE and 10/13/2014 Page 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 L.Frewer eds. The Earthscan reader in Risk and Modern Society. London: Earthscan. • Sjoberg, L. 2006. Will the real meaning of affect please stand up. Journal of Risk Research, Vol.9, p.101-­‐108. • Sjoberg, L. 2008. Antagonism, trust and perceived risk. Risk Management, Vol. 10, p. 32-­‐55. • Lofstedt, R.E. 2003. Science communication and the Swedish acrylamide 'alarm'. Journal of Health Communication, vol. 8, p. 407-­‐430. • Department for Work and Pensions. (2011). The Government response to the Lofstedt Report. EXAM 1 • Lofstedt, R. 2011. Risk versus hazard-­‐how to regulate in the 21st century. European Journal of Risk Regulation, Vol. 2, p. 149-­‐168. • Alberlkop, A. et al. 2011. Lessons from the EU's REACH programme. EJRR, 2, 181-­‐182. • Lofstedt, R. 2013. The informal European Parliamentary Working Group on Risk–History, Remit, and Future Plans: A Personal View. Risk Analysis, 33(7), 1182-­‐1187. • Sunstein, C. R. (2002). Risk and reason: Safety, law, and the environment (pp. 191-­‐250). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. • Lofstedt, R. E. (2004). The swing of the regulatory pendulum in Europe: From precautionary principle to (regulatory) impact analysis. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 28(3), 237-­‐260. • Lofstedt, R., Bouder, F., Chakraborty, S. (2012). Transparency and the Food and Drug Administration–A Quantitative Study. Journal of Health Communication, 0, 1-­‐6. • Chakraborty, S. Lofstedt, R. (2012). Transparency Initiative by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER): Two qualitative studies of Public Perceptions. EJRR, 1, 57-­‐71. • Lofstedt, R. (2013). Transparency at the EMA: More Evidence Is Needed. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 0, 1-­‐2. • Lofstedt, R. E. (2008). Risk communication, media amplification and the aspartame scare. Risk Management, 10, 257-­‐284. • Lofstedt, R. (2013). The substitution principle in chemical regulation: a constructive critique. Journal of Risk Research, 1-­‐22. • Readings TBA EXAM 2 • Löfstedt RE. Evaluation of two siting strategies: The case of two UK waste tire incinerators. Risk Health Safety and Environment, 1997; 8:63-­‐77. • Löfstedt RE. Good and bad examples of sitting and building biosafety level 4 laboratories: a study of Winnipeg, Galveston and Etobicoke. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2002; 93: 47-­‐66. • Löfstedt RE. Public perceptions of the Mars sample return program in Space Policy, 2003; 19:283-­‐292. 10/13/2014 Page 10 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Hamilton, D. and Quinlan, J. (2014) The Transatlantic Economy 2014: Annual Survey of Jobs, Trade and Investment between the United States and Europe, JHU/SAIS, available online at http://transatlantic.sais-­‐ jhu.edu/publications/books/TA2014/TA2014_Vol_1.pdf. • Doing Business in the East African Community 2013: Conditions for SMEs, “getting credit” • Doing Business in the East African Community 2013: Conditions for SMEs, “executive summary”, “measuring for impact”, “starting a business”. • Doing Business in South East Europe 2011, “executive summary” and pp 14-­‐37 • Readings TBA • Readings TBA • Hutter, B. M. (2005). "The Attractions of Risk-­‐based Regulation: accounting for the emergence of risk ideas in regulation." Centre for analysis of risk and regulation discussion papers (33). • Coglianese, C., Finkel, A. M. and D. Zaring (2009). Consumer Protection in an Era of Globalization. Import Safety. Regulatory Governance in the Global Economy. C. Coglianese, A. M. Finkel and D. Zaring. Philadelphia, Univ of Pennsylvania Pr: 151-­‐170. • Graham, J. D., Green, L. C., & Roberts, M. J. (1988). In search of safety: Chemicals and cancer risk (pp. 80-­‐114). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. • Graham, J. D. & Wiener, J. B. (1995). Confronting risk tradeoffs. In Graham, J. D. & Wiener, J. B. (Eds.), Risk vs. risk: Tradeoffs in protecting health and the environment (pp. 1-­‐41). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. • Doing Business Report 2014, “executive summary”. • Doing Business in the East African Community 2013: Conditions for SMEs, “registering property” and “protecting investors”. • Readings TBA EXAM 3 • On the WTO website, the “Overview” and chapter 3, “Settling Disputes,” under “Understanding the WTO”. http://www.wto.org/english/thewto.org/english/thewto_e/wto_dg _stat_e.html • Laine Skoba. “Principal EU-­‐US Trade Disputes”. Library Briefing. Library of the European Parliament. 22/04/2013. 130519REV1. • David Vogel. “Food Safety and Agriculture” (Chapter 3). The Politics of Precaution: Regulating Health, Safety, and Environmental Risks in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press. 2012, 43-­‐102. • Charles E Hanrahan. “Agricultural Biotechnology: The US-­‐EU Dispute”. Congressional Research Service. April 8, 2010. • Jacques Lecarte. China’s Export Restrictions on Rare Earth Elements. Library Briefing. Library of European Parliament. 18/07/2013. 1030357REV1. • Agence France-­‐Presse. WTO Confirms China Rare Earth Trade Limits Break 10/13/2014 • Page 11 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 Rules. Industry Week. August 7, 2014. • Worsfold, D. (2005). "Promoting excellence in food hygiene." Nutrition & Food Science 35(1): 6-­‐14. • Renee Johnson. “US-­‐EU Poultry Dispute”. Congressional Research Service. December 9, 2010. • Deutch, J. (2011). The Good News about Gas: The Natural Gas Revolution and Its Consequences. Foreign Affairs. January/February 2011, 82-­‐93. • Kantner, J. (2013). Europe Votes to Tighten Rules on Drilling Method. New York Times. October 9, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/10/business/energy-­‐ environment/european-­‐lawmakers. • RTT Staff Writer. (2014). European Commission Recommends Minimum Principles for Shale Gas Fracking. January 22, 2014, http://www.rttnews.com/2255021/european-­‐commission-­‐recommends-­‐ minimum-­‐principles. retrieved 3/23/2014. EXAM 4 • • Graham, J. D. & Hu, J. (2007). The risk-­‐benefit balance in the United States: Who decides? Health Affairs, 26(3), 625-­‐635. • Lofstedt, R. E. & Vogel, D. (2001). The changing character of regulation: A comparison of Europe and the United States. Risk Analysis, 21(3), 399-­‐405. • Ban College Football. (2012). Intelligence Squared U.S. Debates. May 8, 2012. New York University. Posted at: http://fora.tv/2012/05/08/Ban_College_Football • Required: Chapters 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 (Introduction and Opening Arguments from Gladwell, Green, Bissinger, and Whitlock) (~36 min). Recommended: Chapters 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 (Rebuttals, Closing Statements, Debate Result) (~35min) Student Presentations Student Presentations 10/13/2014 Page 12