Five classic components MIPS operations and operands MIPS

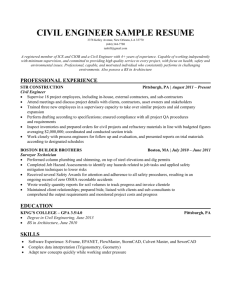

advertisement

Five classic components

I am like a control

tower

CS/COE0447: Computer Organization

and Assembly Language

Chapter 2

I am like a pack of

file folders

I exchange information

with outside world

I am like a conveyor

belt + service stations

Sangyeun Cho

Dept. of Computer Science

University of Pittsburgh

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

2

MIPS operations and operands

Operation specifies what function to perform by the instruction

O

Operand

d specifies

ifi with

ith what

h t a specific

ifi function

f

ti is

i to

t be

b performed

f

d by

b

the instruction

MIPS operations

p

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

MIPS arithmetic

All arithmetic instructions have 3 operands

• Two source registers and one target or destination register

Examples

• add $s1, $s2, $s3

• sub $s4, $s5, $s6

Registers

Fixed registers (e.g., HI/LO)

Memory location

Immediate value

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

<op>

p <rtarget> <rsource1> <rsource2>

• Operand

O

d order

d iin notation

t ti iis fi

fixed;

d ttargett fi

firstt

Arithmetic (integer/floating-point)

Logical

Shift

Compare

Load/store

Branch/jump

System control and coprocessor

MIPS operands

•

•

•

•

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

3

# $s1 ⇐ $s2 + $s3

# $s4 ⇐ $s5 – $s6

University of Pittsburgh

4

MIPS registers

$zero

$at

$v0

$v1

$a0

$a1

$a2

$a3

$t0

$t1

$t2

$t3

$t4

$

$t5

$t6

$t7

General-purpose

General

purpose registers (GPRs)

32 bits

32 bits

r0

r1

r2

r3

r4

r5

r6

r7

r8

r9

r10

r11

r12

r13

3

r14

r15

r16

r17

r18

r19

r20

r21

r22

r23

r24

r25

r26

r27

r28

r29

29

r30

r31

32 bits

$s0

$s1

$s2

$s3

$s4

$s5

$s6

$s7

$t8

$t9

$k0

$k1

$gp

$

$sp

$fp

$ra

General-Purpose

p

Registers

g

The name GPR implies that all these registers can be used as

operands in instructions

Still,, conventions and limitations exist to keep

p GPRs from

being used arbitrarily

HI

LO

• $0, termed $zero, always has a value of “0”

• $31, termed $ra (return address), is reserved for storing the return

address

dd

ffor subroutine

b

call/return

ll

• Register usage and related software conventions are typically

summarized in “application binary interface” (ABI) – important when

writing

g system

y

software such as an assembler or a compiler

p

PC

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

32 GPRs in MIPS

• Are they sufficient?

Special-Purpose

p

p

Registers

g

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

5

Special-purpose

Special

purpose registers

6

Instruction encoding

HI/LO registers

g

are used for storing

g result from multiplication

p

operations

Instructions are encoded in binary numbers

• Assembler translates assembly programs into binary numbers

• Machine (processor) decodes binary numbers to figure out what the

original instruction is

PC (program counter)

• MIPS has a fixed,

fixed 32

32-bit

bit instruction encoding

• Always keeps the pointer to the current program execution point;

instruction fetching occurs at the address in PC

• Not directly visible and manipulated by programmers in MIPS

Other architectures

Encoding should be done in a way that decoding is easy

MIPS instruction formats

•

•

•

•

• May not have HI/LO; use GPRs to store the result of multiplication

• May allow storing to PC to make a jump

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

R-format: arithmetic instructions

I-format: data transfer/arithmetic/jump instructions

J-format: jump instruction format

(FI-/FR-format: floating-point instruction format)

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

7

University of Pittsburgh

8

MIPS instruction formats

Name

Fields

Instruction encoding example

Comments

Field Size

6 bits

5 bits

5 bits

5 bits

5 bits

6 bits

All MIPS instructions 32 bits

R-format

op

rs

rt

rd

shamt

funct

Arithmetic/logic instruction format

I-format

J-format

op

rs

rt

op

address/immediate

target address

Data transfer, branch, immediate

format

Instruction

Format

op

rs

rt

rd

shamt

funct

immediate

add

R

000000

reg

reg

reg

00000

100000

NA

sub

R

000000

reg

reg

reg

00000

100010

NA

addi

(add immediate)

I

00 000

001000

reg

reg

NA

NA

NA

constant

lw

(load word)

I

100011

reg

reg

NA

NA

NA

address offset

sw

(store word)

I

101011

reg

reg

NA

NA

NA

address offset

Jump instruction format

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

9

Logic instructions

Name

R-format

Dealing with immediate

Fields

op

rs

rt

rd

shamt

10

funct

Comments

Name

Logic instruction format

I-format

Bit-wise logic operations

<op> <rtarget> <rsource1> <rsource2>

E

Examples

l

• nor $s3, $t2, $s1

• xor $s3, $s2, $s1

rs

rt

16-bit immediate

T n fe branch,

Transfer,

b n h immediate

immedi te

format

Many operations involve small “immediate” value

Some frequently

freq entl used

sed arithmetic/logic instruction

instr ction shave

sha e their

“immediate” version

•

•

•

•

# $t3 ⇐ $t2 | $t1

# $s3 ⇐ ~($t2 | $s1)

# $s3 ⇐ $s2 ^ $s1

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

op

Comments

• a=a+1

• b=b–4

• c = d | 0x04

• and $s3, $s2, $s1 # $s3 ⇐ $s2 & $s1

• or $t3, $t2, $t1

Fields

addi $s3, $s2, 16

andi $s5, $s4, 0xfffe

ori $t4,

$t4 $t4

$t4, 4

xori $s7, $s6, 16

# $s3 ⇐ $s2 + 16

# $s5 ⇐ $s4 & 1111111111111110b

# $t4 ⇐ $t4 | 0000000000000100b

# $s7 ⇐ $s6 ^ 0000000000010000b

There is no “subi”; why?

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

11

University of Pittsburgh

12

Handling long immediate number

Memory transfer instructions

Sometimes we need a long

g immediate value, e.g.,

g 32 bits

Also called memory access instructions

Only two types of instructions

• Do we need an instruction to load a 32-bit constant value to a

register?

MIPS requires

q

that we use two instructions

• Load: move data from memory

y to register

g

e.g., lw $s5, 4($t6)

• lui $s3, 1010101001010101b

$s3

e.g., sw $s7, 16($t3)

1010101001010101 0000000000000000

Then we fill the low-order 16 bits

• ori $s3, $s3, 1100110000110011b

$s3

# memory[$t3+16] ⇐ $s7

In MIPS (32-bit architecture) there are memory transfer

instructions for

• 32-bit word: “int” type in C

• 16-bit half-word: “short” type in C

• 8-bit byte: “char” type in C

1010101001010101 1100110000110011

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

# $s5 ⇐ memory[$t6 + 4]

• Store: move data from register to memory

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

13

Address calculation

14

Machine code example

Memoryy address is specified

p

with a (register,

g

constant) p

pair

• Register to keep the base address

• Constant field to keep the “offset” from the base address

void swap(int v[], int k)

{

int temp;

temp = v[k];

v[k] = v[k+1];

v[k+1] = temp;

}

• Address is,, then,, ((register

g

+ offset))

• The offset can be positive or negative

MIPS uses this simple address calculation method; other

architectures such as PowerPC and x86 support different

methods

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

15

swap:

sll

add

lw

lw

sw

sw

jr

$t0,

$t1,

$t3,

$t4,

$t4

$t4,

$t3,

$ra

$a1, 2

$a0, $t0

0($t1)

4($t1)

0($t1)

4($t1)

University of Pittsburgh

16

Memory view

0

BYTE #0

1

BYTE #1

2

BYTE #2

3

BYTE #3

4

BYTE #4

5

BYTE #5

32-bit byte address

• 232 bytes

b t with

ith byte

b t addresses

dd

from

f

0 tto

232 – 1

• 230 words with byte addresses 0, 4, 8, …,

232 – 4

Words are aligned

• 2 least significant bits (LSBs) of an

address are 0s

0

WORD

4

WORD

8

WORD

12

WORD

16

WORD

20

WORD

Half words are aligned

• LSB of an address is 0

MSB

Addressing within a word

0

the last?

• Big-endian vs. little-endian

0

• Which byte appears first and which byte

…

Memoryy is a large,

g single-dimension

g

8-bit (byte)

y arrayy with

an address to each 8-bit item (“byte address”)

A memory address is an index into the array

…

Memory organization

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

0

2

2

1

MSB

3

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

LSB

1

3

LSB

0

University of Pittsburgh

17

More on alignment

A misaligned access

• lw $s4, 3($t0)

More on alignment

How do we define a word at address?

• Data in byte 0, 1, 2, 3

0

0

1

4

4

5

6

7

8

8

9

10

11

If you meant this, use the address 0, not 3

• Data in byte 3, 4, 5, 6

2

int main()

{

int A[100];

int i;

int *ptr;

3

for (i = 0; i < 100; i++) A[i] = i;

…

18

printf("address of A[0] = %8x\n", &A[1]);

printf("address of A[50] = %8x\n", &A[50]);

ptr

t = &A[50];

&A[50]

If you meant this, it is indeed misaligned!

Certain hardware implementation may support this; usually not

If you still want to obtain a word starting from the address 3 – get a byte

from address 3, a word from address 4 and manipulate the two data to

get what you want

printf("address in ptr = %8x\n", ptr);

printf("value pointed by ptr = %d\n", *ptr);

}

address of A[0] = bffff2b4

address of A[50] = bffff378

address in ptr = bffff378

value pointed by ptr = 50

address in ptr = bffff379

Segmentation fault

ptr = (int*)((unsigned int)ptr + 1);

printf("address

f( dd

in ptr = %8x\n", ptr);

)

printf("value pointed by ptr = %d\n", *ptr);

Alignment issue does not exist for byte access

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

19

University of Pittsburgh

20

Shift instructions

Name

R-format

Control

Fields

NOT

USED

op

rt

Comments

rd

shamt

funct

Instruction that potentially changes the flow of program execution

MIPS conditional branch instructions

shamt is “shift amount”

Bits change their positions inside a word

<op> <rtarget> <rsource> <shift_amount>

• bne $s4, $s3, LABEL

• beq $s4, $s3, LABEL

Examples

if (i == h) h =i+j;

# $s3 ⇐ $s4 << 4

# $s6 ⇐ $s5 >> 6

• sll $s3, $s4, 4

• srl $s6, $s5, 6

Example

YES

Shift amount can be in a register (in that case “shamt”

shamt is not

used)

Shirt right arithmetic (sra) keeps the sign of a number

(i == h)?

h=i+j;

LABEL:

• sra $s7,

$ 7 $

$s5,

5 4

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

NO

bne $s5,

b

$ 5 $s6,

$ 6 LABEL

add $s6, $s6, $s4

LABEL: …

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

21

Control

Control

MIPS unconditional branch instruction (i.e., jump)

j p

• j LABEL

22

Loops

p

• “While” loops

Example on page 74

Example

• “For” loops

• f,

f g,

g and h are in registers $s5

$s5, $s6

$s6, $s7

if (i == h) f=g+h;

else f=g–h;

YES

(i == h)?

NO

f=g+h;

bne $t6, $s7, ELSE

add $

$s5,, $s6,

$ , $s7

$

j EXIT

ELSE: sub $s5, $s6, $s7

EXIT: …

f=g–h

EXIT

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

23

University of Pittsburgh

24

Control

Address in II-format

format

We have beq

q and bne; what about branch-if-less-than?

Branch/

Immediate

• We have slt

if (s1<s2) t0=1;

else t0=0;

slt $t0, $s1, $s2

op

rs

rt

16-bit

16

bit immediate

Immediate address in an instruction is not a 32-bit value –

it’s onlyy 16-bit

• The 16-bit immediate value is in signed, 2’s complement form

Can you make a “psuedo” instruction “blt $s1, $s2, LABEL”?

Addressing in branch instructions

• The 16

16-bit

bit number in the instruction specifies the number of

“instructions” to be skipped

• Memory address is obtained by adding this number to the PC

• Next address = PC + 4 + sign_extend(16-bit immediate << 2)

Assembler needs a temporary register to do this

• $at is reserved for this purpose

Example

• beq $s1, $s2, 100

4

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

17

18

25

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

25

J format

J-format

26

MIPS addressing modes

Jump

op

26-bit

26

bit immediate

Immediate addressing

g (I-format)

op

The address of next instruction is obtained from PC and the

immediate value

• Next address = {PC[31:28],IMM[25:0],00}

• Address boundaries of 256MB

Example

op

rs

rt

op

rs

rt

2500

rs

rs

27

shamt

h

f

funct

immediate

rt

offset

rt

offset

Pseudo-direct addressing (j) [concatenation w/ PC]

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

rd

d

PC-relative addressing (beq/bne) [PC + 4 + offset]

op

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

immediate

Base addressing (load/store) – [register + offset]

op

2

rt

Register addressing (R-/I-format)

op

• j 10000

rs

26-bit

26

bit address

University of Pittsburgh

28

MIPS instructions

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

Register usage convention

NAME

REG. NUMBER

$zero

0

zero

$at

1

reserved for assembler usage

values for results and expression eval.

$v0~$v1

2~3

$a0~$a3

4~7

arguments

$t0~$t7

8~15

temporaries

$s0~$s7

16~23

temporaries, saved

$t8~$t9

24~25

more temporaries

$k0~$k1

26~27

reserved for OS kernel

$gp

28

global pointer

$sp

29

stack pointer

$fp

30

frame pointer

$ra

31

return address

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

USAGE

University of Pittsburgh

29

Stack and frame pointers

30

“C”

C program down to numbers

Stack pointer ($sp)

• Keeps

K

the

th address

dd

to

t th

the ttop off

the stack

• $29 is reserved for this purpose

• Stack grows from high address to

low

• Typical stack operations are

push/pop

swap:

Procedure frame

• Contains

C

i saved

d registers

i

and

d llocall

variables

muli

add

dd

lw

lw

sw

sw

jr

$2, $5, 4

$2 $4,

$2,

$4 $2

$15, 0($2)

$16, 4($2)

$16, 0($2)

$15, 4($2)

$31

• “Activation record”

Frame pointer ($fp)

•

•

•

•

Points to the first word of a frame

Offers a stable reference pointer

$30 is reserved for this

Some compilers

p

don’t use $

$fp

p

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

31

void swap(int

p(

v[],

[], int k))

{

int temp;

temp = v[k];

v[k] = v[k+1];

v[k+1] = temp;

}

00000000101000010…

00000000000110000…

10001100011000100…

10001100111100100…

10101100111100100…

10101100111100100

10101100011000100…

00000011111000000…

University of Pittsburgh

32

Producing a binary

Assembler

Expands macros

• Macro is a sequence of operations conveniently defined by a user

• A single macro can expand to many instructions

source file

.asm/.s

assembler

object file

.obj/.o

source file

.asm/.s

assembler

object file

.obj/.o

linker

source file

.asm/.s

assembler

object file

.obj/.o

library

.lib/.a

Determines addresses and translates source into binary

numbers

•

•

•

•

executable

.exe

Start from a pre-defined address

Record in “symbol table” addresses of labels

Resolve

l b

branch

h targets and

d complete

l

b

branch

h iinstructions’

i

encoding

di

Record instructions that need be fixed after linkage

Packs everything in an object file

“Two-pass assembler”

• To handle forward references

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

33

Object file

34

Important assembler directives

Header

• Size

Si and

d position

i i off other

h pieces

i

off the

h fil

file

Assembler directives guide the assembler to properly

h dl source code

handle

d with

i h certain

i considerations

id

i

.text

Text segment

Data segment

Relocation information

.data

.align

• Machine codes

• Tells assembler that a “code” segment follows

• Binary representation of the data in the source

• Identifies instructions and data words that depend on absolute

• Tells assembler that a “data” segment

g

follows

addresses

dd

Symbol table

• Directs aligning following items

• Keeps addresses of global labels

• Lists unresolved references

.global

• Contains a concise description of the way in which the program was

.asciiz

Debugging information

• Tells to treat following symbols as global

compiled

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

• Tells to handle following input as a “string”

string

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

35

University of Pittsburgh

36

Code example

.text

.align

align

.globl

Macro example

.data

2

main

int str:

int_str:

subu

…

$sp, $sp, 32

.macro

lw

…

la

lw

jal

…

jr

$t6, 28($sp)

main:

loop:

.data

.align

$a0, str

$a1, 24($sp)

printf

.asciiz “%d”

.text

print_int($arg)

la $a0, int_str

mov $a1, $arg

jal printf

.end_macro

…

print_int($7)

$ra

la $a0, int_str

mov $a1, $7

jal printf

0

str:

.asciiz

ii

“Th sum f

“The

from 0 … 100 i

is %d\

%d\n”

”

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

37

Linker

38

Procedure call

Argument

g

passing

p

g

• First 4 arguments are passed through $a0~$a3

• More arguments are passed through stack

Result passing

• First 2 results are passed through $v0~$v1

• More results can be passed through stack

Stack manipulations can be tricky and error-prone

• Application binary interface (ABI) has formal treatment of

procedure

d

calls

ll and

d stack

k manipulations

i l i

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

More will be discussed in labs.

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

39

University of Pittsburgh

40

High-level

High

level language

High-level language

Example

C, Fortran, Java, …

Interpreter vs. compiler

Interpreter

Compiler

Concept

Line-by-line translation and

execution

u o

Whole program translation and

native

a

execution

u o

Example

Java, BASIC, …

C, Fortran, …

Assembly

-

+

High productivity

– Short description & readability

Portability

Low productivity

– Long description & low readability

Not portable

+

Interactive

Portable (e.g., Java Virtual Machine)

High performance

–

Limited optimization capability in

certain cases

With p

proper

p knowledge

g and

experiences, fully optimized codes

can be written

–

Low performance

Binary not portable to other

machines or generations

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

41

Compiler structure

42

Compiler front

front-end

end

Compiler

p

is a veryy complex

p

software with a varietyy of

functions and algorithms implemented inside it

Scanning

• Takes

T k the

th input

i

t source program and

d chops

h

th

the programs iinto

t

recognizable “tokens”

• Also known as “lexical analysis” and “LEX” tool is used

Front end

Front-end

• Deals with high-level language constructs and translates them into

• “YACC” or “BISON” tools are used

Semantic analysis

IR generation

i

Back-end

• Takes the abstract syntax trees, performs type checking, and

builds a symbol table

• Back-end

k d IR more or lless correspond

d to machine

hi iinstructions

i

• With many compiling steps, IR items becomes machine instructions

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

• Takes the token stream, checks the syntax, and produces

abstract syntax trees

more relevant tree-like or list-format internal representation (IR)

• Symbols (e

(e.g.,

g a[i+8*j]) are still available

Parsing

g

• Similar to assembly language program, but assumes unlimited

registers, etc.

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

43

University of Pittsburgh

44

Compiler back

back-end

end

Code & abstract syntax tree

Local optimization

• Optimizations within a basic block

• Common sub-expression elimination (CSE), copy propagation,

while

hil (

(save[i]

[i] == k)

i+=1;

constant propagation, dead code elimination, …

Global optimization

Loop optimizations

• Optimizations that deal with multiple basic blocks

• Loops are so important that many compiler and architecture

optimizations

i i i

target them

h

• Induction variable removal, loop invariant removal, strength

reduction, …

Register

g

allocation

Machine-dependent optimizations

• Try to keep as many variables in registers as possible

• Utilize any useful instructions provided by the target machine

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

45

Internal representation

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

46

Control flow graph

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

47

University of Pittsburgh

48

Loop optimization

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

Register allocation

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh

49

Compiler example: gcc

gcc = GNU open-source C Compiler

cpp: C pre-processor

Compiler optimization

is not uncommon

cc1: C compiler

p

((front-end & back-end))

• Not that serious in many cases as compiling is a rare event

gas: assembler

compared to program execution

• Considering the resulting code quality, you pay this fee

• Now, computers are fast!

• Assembles compiler-generated

p

g

assemblyy codes

ld: linker

• Links all the object files and library files to generate an executable

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

Turning on optimizations may incur a significant

compile time overhead

• For a big, complex software project, compile time is an issue

• Compiles your C program

Optimizations

p

are a must

• Code quality can be much improved; 2~10 times improvement

• Macro expansion

p

((#define))

• File expansion (#include)

• Handles other directives (#if, #else, #pragma)

50

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

51

University of Pittsburgh

52

Wrapping up

MIPS ISA

• Typical RISC style architecture

• 32 GPRs

• 32-bit instruction format

• 32-bit address space

Operations & operands

Arithmetic, logical,

g

memoryy access, control instructions

Compiler, interpreter, …

CS/CoE0447: Computer Organization and Assembly Language

University of Pittsburgh

53