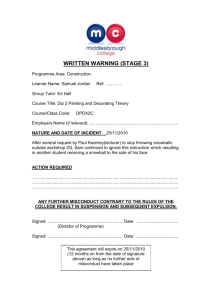

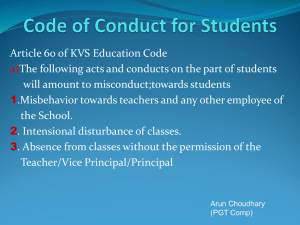

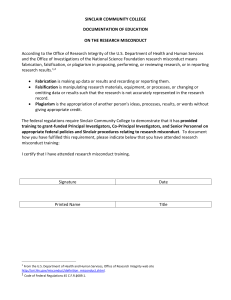

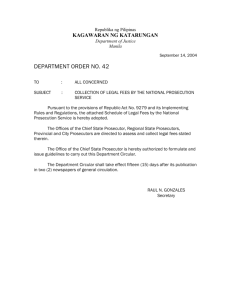

Prosecutorial Misconduct

advertisement