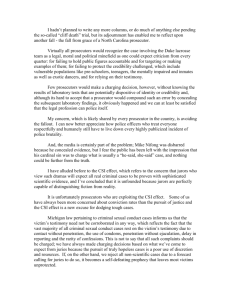

Prosecutorial Shaming: Naming Attorneys to Reduce Prosecutorial

advertisement