A Meta-Analysis of Outcome Studies Comparing Bona Fide

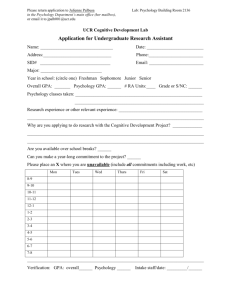

advertisement