An Octoroon in the Kindling”

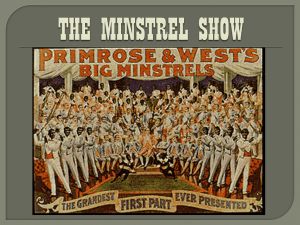

advertisement