FIRST NAME LAST NAME

advertisement

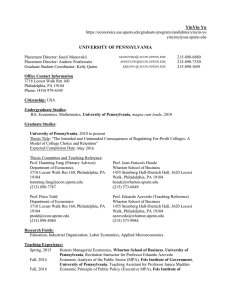

CHUNZAN WU https://economics.sas.upenn.edu/graduate-program/candidates/chunzan-wu chunzan@sas.upenn.edu UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MANOVSKI@ ECON.UPENN.EDU Placement Director: Iourii Manovskii Placement Director: Andrew Postlewaite Graduate Student Coordinator: Kelly Quinn APOSTLEW@ECON.UPENN.EDU KQUINN @ ECON.UPENN.EDU 215-898-6880 215-898-7350 215-898-5691 Office Contact Information 160 McNeil Building, 3718 Locust Walk Philadelphia, PA 19104 Phone: 530-219-7231 Personal Information Citizenship: China Undergraduate Studies B.S., Chemistry, Peking University, 2004 B.A., Economics, Peking University, 2004 Masters Level Work M.A., Economics, Peking University, 2007 Graduate Studies University of California, Davis, 2009 to 2011 University of Pennsylvania, 2011 to present Thesis Title: “Macroeconomic and Fiscal Policy Implications of Household Labor Supply” Expected Completion Date: June 2016 Thesis Committee and References: Professor Dirk Krueger (Primary Advisor) Department of Economics, University of Pennsylvania, 3718 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA Phone: (215) 573-1424 Email: dkrueger@econ.upenn.edu Professor Harold L. Cole Department of Economics, University of Pennsylvania, 3718 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA Phone: (215) 898-7788 Email: colehl@sas.upenn.edu Professor Guido Menzio Department of Economics, University of Pennsylvania, 3718 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA Phone: (215) 898-5170 Email: gmenzio@sas.upenn.edu Teaching and Research Fields Primary fields: Macroeconomics Secondary fields: Public Finance, Labor Economics, Computational Economics 1 Teaching Experience Ph.D. Level Spring, 2014 Macroeconomic Theory I , University of Pennsylvania, Teaching Assistant for Spring, 2013 Professor Dirk Krueger And Professor Jesus Fernandez-Villaverde Undergraduate Level Fall, 2015 Macroeconomic Theory, University of Pennsylvania, Teaching Assistant for Professor Dirk Krueger Spring, 2015 Macroeconomic Theory, University of Pennsylvania, Teaching Assistant for Professor Guido Menzio Fall, 2014 Macroeconomic Theory, University of Pennsylvania, Teaching Assistant for Professor Guillermo Ordonez Fall, 2013 Statistics for Economists ,University of Pennsylvania, Teaching Assistant for Professor Francis J. DiTraglia Fall, 2012 International Trade, University of Pennsylvania, Teaching Assistant for Professor Wilfred J. Ethier Research Experience and Other Employment Fall, 2013 University of Pennsylvania, Research Assistant for Professor Mathieu Taschereau-Dumouchel Spring, 2013 University of Pennsylvania, Research Assistant for Professor Iourii Manovskii Honors, Scholarships, and Fellowships 2015 Joel Popkin Graduate Student Teaching Prize in Economics for outstanding teaching performance by a teaching assistant in economics, University of Pennsylvania 2012 Lawrence Robbins Prize in Economics to the student judged to be the best in the first year class, University of Pennsylvania Research Papers: “More Unequal Income but Less Progressive Taxation: Economics or Politics?” (Job Market Paper) Abstract: Since the 1970s, income inequality in the U.S. has increased sharply. During the same time span, the U.S. federal income tax has become less progressive. Why? I examine this question in a Ramsey optimal tax policy framework. Within this framework, the tax policy is determined by: (1) a set of Pareto weights representing the government's preference over different households; and (2) household lifetime utilities summarizing the effects of economic fundamentals. I first study the changes in economic fundamentals using an overlapping generations incomplete-markets life-cycle model with heterogeneous households. The model features both endogenous human capital accumulation and household labor supply and is calibrated to the U.S. economy in the 1970s and 2010s. Then I use this economic model to determine whether the change in income tax is the result of an optimal policy response to changing economic fundamentals or the consequence of a change in Pareto weights. I interpret the latter as changes in the political influences of various income groups. I find that: (1) changes in economic fundamentals alone induce a less progressive optimal income tax and can account for 40% of the reduction in progressivity we observe; and (2) the change in Pareto weights required to explain the remaining part of tax policy change favors high-income households and also implies less valued government services. Finally, using a stylized political economy model, I discuss potential explanations for this change in Pareto weights such as the lower cost of conveying information to swing voters and the rising inequality of voter turnout among different socioeconomic groups. 2 “How Much Consumption Insurance in Bewley Models with Endogenous Family Labor Supply?” (with Dirk Krueger) Abstract: We show that a calibrated life-cycle two-earner household model with endogenous labor supply can rationalize the extent of consumption insurance against wage shocks estimated empirically by Blundell, Pistaferri, and Saporta-Eksten (2014) (BPS hereafter) in the U.S. data. With additive separable preferences, the model can account for about 94% and 91% of consumption insurance against male and female permanent wage shocks in the data, and only 41% of male and 28% of female permanent wage shocks in the model pass through to household consumption. With non-separable preferences, more consumption insurance is generated, and the pass-through rates are 27% and 18%, respectively. Most notably, the majority of the consumption insurance against permanent male wage shocks is provided through the endogenous labor supply response of the female earner. We also evaluate, using model-simulated data, whether the empirical approach of BPS delivers unbiased consumption responses to wage shocks. We find that the method overestimates the amount of consumption insurance against male permanent wage shocks, and underestimates that against female permanent wage shocks, but only moderately so. We find larger biases for the outside insurance coefficient which BPS use to capture the insurance provided through channels outside their model. We document that the magnitudes of the biases are not sensitive to the existence of tight borrowing constraints or the presence of an extensive female labor supply margin given their implementation method. 3