Stuck in the Impasse: Cynicism as Neoliberal Affect

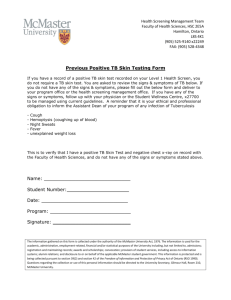

advertisement